You've probably seen it. That minimalist grid of black-and-white illustrations showing a person doing jumping jacks, wall sits, and planks. It looks almost too simple. When the NYTimes seven minute workout first blew up back in 2013, it felt like a cheat code. Everyone was obsessed with the idea that you could basically skip the hour-long gym grind and just sweat for the length of two pop songs. But honestly? Most people still do it wrong because they treat it like a casual stretch rather than what it actually is: a high-intensity interval training (HIIT) protocol backed by real physiological science.

It’s not magic. It’s "High-Intensity Circuit Training Using Body Weight: Maximum Results With Minimum Investment." That was the actual title of the paper published in the ACSM’s Health & Fitness Journal by Chris Jordan and Brett Klika. They weren't trying to make a viral hit for the New York Times; they were trying to solve a problem for busy people who had zero equipment and even less time.

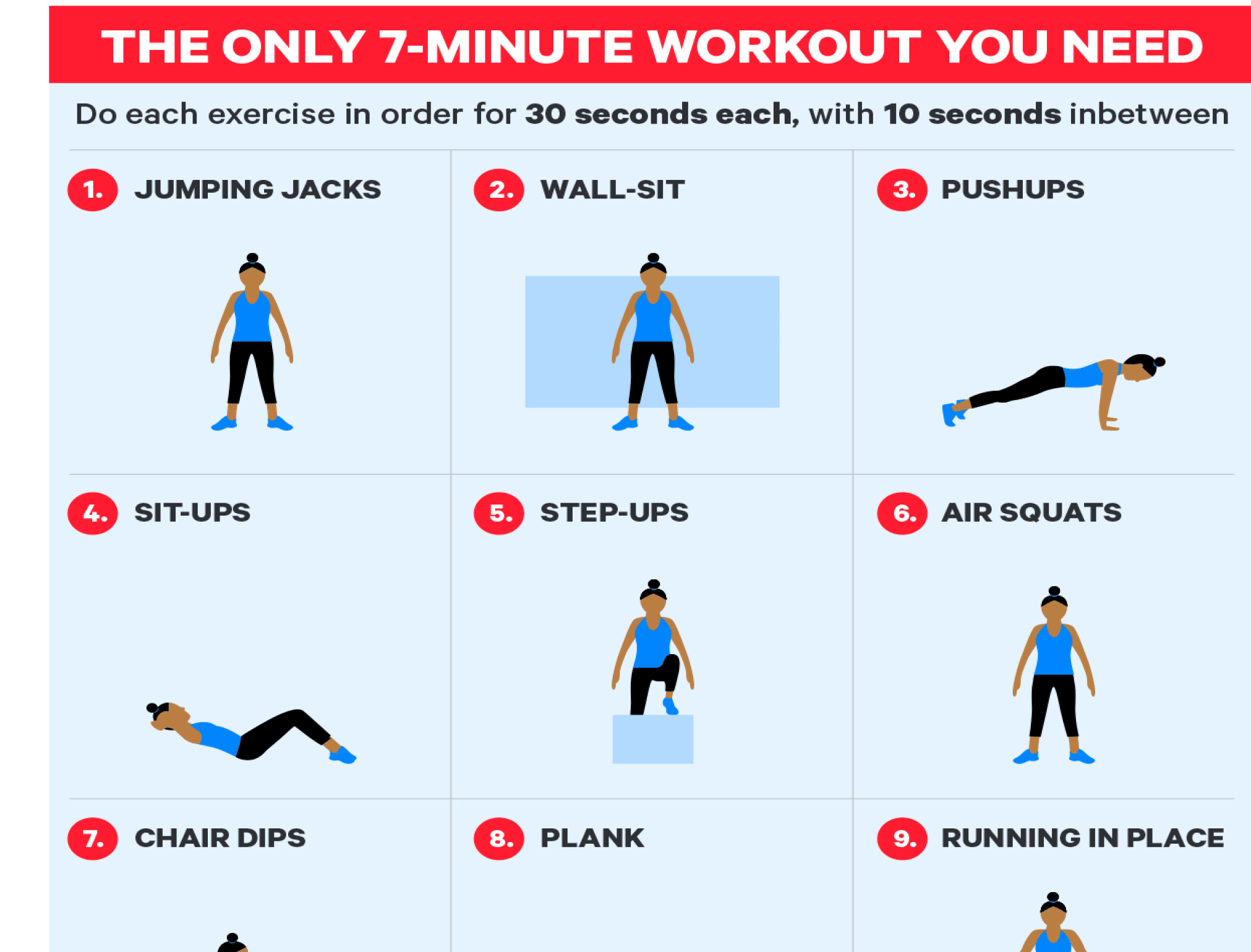

The workout is basically a gauntlet. You do 12 exercises. 30 seconds each. 10 seconds of rest in between. That’s it. But if you aren't gasping for air by the time you hit the side planks, you’re likely coasting.

The Science of Why This Specific Seven Minutes Works

The whole "seven minutes" thing sounds like a late-night infomercial pitch, but the biology is pretty solid. It relies on something called excess post-exercise oxygen consumption, or EPOC. Basically, by redlining your heart rate in such a short window, your body keeps burning calories long after you’ve hopped in the shower. You're creating an oxygen debt. Your body has to work overtime to get back to its baseline state, and that takes energy.

I’ve talked to trainers who hate this workout because they think it discourages "real" lifting. I disagree. It’s a gateway drug to movement. For someone sitting at a desk in New York or London for nine hours a day, the barrier to entry for a 60-minute CrossFit class is huge. The barrier for the NYTimes seven minute workout is just standing up.

The 12 Movements in Order

- Jumping jacks (Total body)

- Wall sit (Lower body)

- Push-up (Upper body)

- Abdominal crunch (Core)

- Step-up onto chair (Lower body)

- Squat (Lower body)

- Triceps dip on chair (Upper body)

- Plank (Core)

- High knees/running in place (Cardio)

- Lunge (Lower body)

- Push-up and rotation (Upper body/Core)

- Side plank (Core)

Notice the logic here. It’s a "peripheral heart action" style of training. You go from a leg exercise to an arm exercise to a core exercise. This forces your heart to pump blood rapidly from one extremity to the other, which is why your heart rate stays so high even though you're only moving for 30 seconds at a time. It's smart. It's efficient. It’s also kinda brutal if you actually put in the effort.

🔗 Read more: Exercises to Get Big Boobs: What Actually Works and the Anatomy Most People Ignore

What Most People Get Wrong About Intensity

Here is the cold, hard truth: If you are comfortable during the NYTimes seven minute workout, you are failing. Chris Jordan, the director of exercise physiology at the Johnson & Johnson Human Performance Institute and co-author of the original study, has been very clear about this. On a scale of 1 to 10, your discomfort level should be around an 8.

It should hurt a little. Not "injury" hurt, but "I can't hold a conversation" hurt.

Many people treat the 10-second transitions as a chance to check their phone or grab a sip of water. Don't. Those 10 seconds are barely enough time to get into position for the next move. The moment you let your heart rate drop too far, you lose the metabolic advantage of the circuit.

Also, let’s talk about the chair. People use flimsy rolling office chairs for the step-ups and tricep dips. Please, don't do that. Use a sturdy kitchen chair or a couch. I’ve seen enough "home workout fail" videos to know that a wheel-based chair is a one-way ticket to a floor-face meeting.

Is Seven Minutes Actually Enough for Weight Loss?

This is where the nuance comes in. If you do this workout once a day and then eat a double cheeseburger, you aren't going to see a six-pack. Obviously.

💡 You might also like: Products With Red 40: What Most People Get Wrong

But for cardiovascular health? A study published in Diabetes Care showed that short bursts of high-intensity exercise can improve insulin sensitivity and blood sugar levels in people with Type 2 diabetes. Another study in the Journal of Physiology found that HIIT (the foundation of this workout) can produce similar or even superior improvements in blood pressure and aerobic capacity compared to traditional endurance training.

The NYTimes seven minute workout is a tool. It's not a total fitness solution for a professional athlete, but it's an incredible baseline for a human being trying to stay functional. If you have more time, you’re actually supposed to repeat the circuit two or three times. Doing it three times gives you about 21 minutes of work, which is the "sweet spot" many physiologists recommend for significant aerobic gains.

The Psychological Edge: Overcoming the "I'll Do It Tomorrow" Trap

Fitness is 20% physiology and 80% psychology. We lie to ourselves. We say we don't have time.

You can't say that about seven minutes. You spend seven minutes deciding what to watch on Netflix. You spend seven minutes scrolling through a single Reddit thread. The brilliance of the NYTimes seven minute workout is that it removes the excuse of time. Once you start, you're already 15% done. By the time you feel like quitting, you're on the lunges and there are only three moves left.

It’s a "low-friction" habit. In the world of behavioral science, we talk about reducing the steps between you and the desired action. Since this requires no gym membership, no kettlebells, and no specialized shoes, the friction is basically zero. You can do it in your pajamas. (I have. It’s fine.)

📖 Related: Why Sometimes You Just Need a Hug: The Real Science of Physical Touch

Why It Remains Relevant in 2026

We live in a world of fitness fads. Every week there’s a new app or a new $3,000 piece of equipment that promises to "biohack" your fat cells. Meanwhile, this simple bodyweight routine stays relevant because it’s based on how the human body actually functions, not on a marketing budget.

The NYT even released an "Advanced" version and a "Scientific 7-Minute Workout for Kids," but the original remains the gold standard. It’s the "Old Reliable" of the fitness world. It’s the routine you use when you’re traveling and the hotel gym is just a broken treadmill and a single 5lb dumbbell. It’s what you do when the kids are napping and you have exactly 10 minutes before the next Zoom call.

Actionable Steps to Get Started Right Now

Don't overthink this. If you want to actually see results from the NYTimes seven minute workout, follow these specific tweaks to the standard routine:

- Download a specialized timer. Don't try to look at a wall clock. There are dozens of free "7 Minute Workout" apps that beep when it’s time to switch. It keeps you honest.

- Prioritize form over speed. In the 30 seconds of push-ups, doing 10 "perfect" ones is better for your joints and muscles than doing 30 "garbage" ones where your back sags like a bridge.

- The Wall Sit is a mental game. Keep your thighs parallel to the floor. Most people cheat and stand too high. It should burn. Embrace the burn.

- Breathe. It sounds stupid, but people hold their breath during the plank. That spikes your blood pressure unnecessarily. Deep, rhythmic breaths will help you get through the final 90 seconds.

- The "Double" Strategy. If you’ve been doing this for a week and it feels easy, don't just go faster. Do the whole circuit, rest for 60 seconds, and do it again. That second round is where the real conditioning happens.

The reality is that most people don't need a complex periodized lifting program. They just need to move their bodies with enough intensity to trigger a biological response. The NYTimes seven minute workout provides that. It’s accessible, it’s scientifically grounded, and it’s effectively "no-fail" if you just show up. Stand up, find a wall, grab a chair, and start the timer. Your future self will be glad you did.