Honestly, most people approach the novels of Vladimir Nabokov like they're about to defuse a bomb. There’s this weird, lingering aura of "intellectual elitism" that surrounds his work. You see the name on a bookshelf and immediately think of a guy with a monocle and a dictionary the size of a cinder block. It’s intimidating.

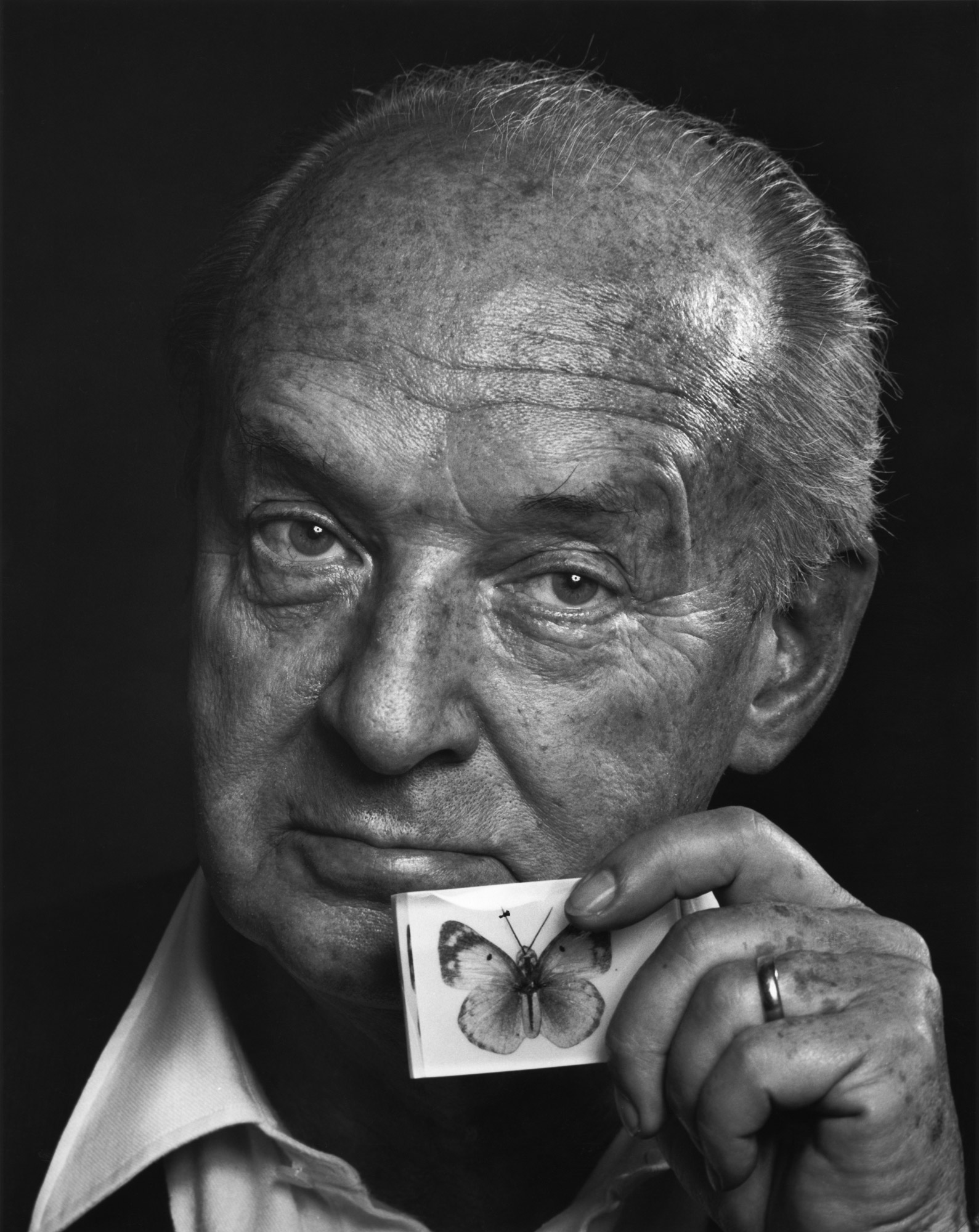

But here’s the thing. Nabokov wasn't just some dusty academic. He was a guy who loved butterflies, hated Freud, and thought most "great" writers were actually kind of boring. He wrote for the senses. If you aren't smelling the damp earth in The Gift or feeling the literal physical chill of the fluorescent lights in Bend Sinister, you're missing the point. He didn't write puzzles; he wrote experiences.

The Lolita problem and why we can't stop talking about it

Let’s just address the elephant in the room immediately. When we talk about the novels of Vladimir Nabokov, everyone starts and usually ends with Lolita. It’s unavoidable. It’s also one of the most misunderstood books in the history of the English language.

People call it a "romance." It isn't. It’s a horror story told by a silver-tongued monster.

Humbert Humbert is perhaps the most dangerous narrator ever put to paper because he is so incredibly charming. He uses his mastery of language to try and trick you, the "ladies and gentlemen of the jury," into sympathizing with a predator. Nabokov’s genius here isn't just the prose—it's the trap. He wants you to get swept up in the beautiful descriptions of the American road trip, only to slap you across the face with the reality of what is actually happening to Dolores Haze.

It’s a book about the total destruction of a child's life, disguised as a travelogue. If you find the prose beautiful, that’s the point. It’s supposed to be seductive. That’s how the trap works.

Forget the "Message": Nabokov hated symbols

One of the biggest mistakes students and casual readers make is looking for "the meaning."

Nabokov famously loathed what he called "topical trash" or "sociological fiction." If you told him his books were a commentary on the Cold War or a metaphor for the Russian soul, he’d probably tell you to go read a newspaper instead. He didn't care about "messages." He cared about the individual. The specific. The "shiver in the spine."

👉 See also: Album Hopes and Fears: Why We Obsess Over Music That Doesn't Exist Yet

Take Pnin, for example.

It’s basically a comedy about a bumbling Russian professor at an American university. It’s hilarious. Truly. Professor Timofey Pnin is a man totally out of sync with his environment, struggling with washing machines and departmental politics. But by the end, you realize you aren't just laughing at him; you’re witnessing the profound dignity of a man who has lost everything—his country, his language, his wife—and yet refuses to be a victim. It’s a small, perfect novel. It doesn't need a "grand theme" because the human detail is enough.

The Russian vs. English divide

You've got to remember that Nabokov’s career is split right down the middle by a language shift that should have been impossible.

- The Russian Years: Writing under the pseudonym V. Sirin in Berlin and Paris. These books are often more experimental in a raw way. Invitation to a Beheading feels like a fever dream or a Kafka story if Kafka had a sense of humor and a better vocabulary.

- The American Years: This is the Nabokov most people know. Pale Fire, Ada, or Ardor, and Look at the Harlequins!.

Switching languages in your 40s and becoming the greatest stylist in your second tongue is a feat that basically no one else has ever pulled off to this degree. Not even Conrad. Nabokov didn't just learn English; he conquered it.

Pale Fire: The ultimate literary prank

If you want to see Nabokov at his most playful (and most devious), you have to look at Pale Fire.

It’s not a normal novel. It’s a 999-line poem written by a fictional poet named John Shade, followed by a massive section of "commentary" by his neighbor, Charles Kinbote.

Kinbote is completely insane.

✨ Don't miss: The Name of This Band Is Talking Heads: Why This Live Album Still Beats the Studio Records

He’s convinced the poem is actually about his own secret life as the exiled king of a faraway land called Zembla. As you read the footnotes, you realize Kinbote is hijacking Shade’s work to tell his own story. It’s a meta-fictional masterpiece that predates the whole "postmodern" movement by years, but it’s much more fun than that sounds. It’s a detective story where you’re the detective, trying to piece together the truth from the ravings of a madman.

Why his prose feels "different"

Ever notice how some books feel like they were written by a committee? Nabokov’s novels of Vladimir Nabokov feel like they were carved out of marble by a guy who was laughing the whole time.

He used index cards.

He didn't write from start to finish. He wrote scenes on cards and shuffled them until the pattern felt right. This is why his books feel so dense with detail—every single sentence has been polished until it glows. He wasn't interested in "flow" in the traditional sense; he wanted precision.

He once said, "I think like a genius, I write like a distinguished author, and I speak like a child." That self-awareness is everywhere in his work. He knows he’s performing for you. He’s the director, the actor, and the guy selling popcorn in the back.

The overlooked gems

While everyone fights over Lolita, some of his best work sits quietly in the corner.

- Laughter in the Dark: This is essentially a noir thriller. A man falls for a younger woman, she and her lover conspire to ruin him, and things go very, very wrong. It’s mean, lean, and incredibly cinematic.

- The Defense: This one is for the gamers or anyone who has ever been obsessed with a hobby. It’s about a chess grandmaster who starts seeing the real world as a series of chess moves. It captures the feeling of a mental breakdown better than almost any other book I’ve read.

- Ada, or Ardor: This is the "final boss" of Nabokov novels. It’s long, it’s set on a version of Earth called "Antiterra," and it’s deeply strange. It’s a family chronicle that spans generations. It’s also incredibly difficult, but the descriptions of nature and time are some of the best he ever wrote.

Dealing with the "Arrogance"

Let’s be real: Nabokov could be a jerk.

🔗 Read more: Wrong Address: Why This Nigerian Drama Is Still Sparking Conversations

He publicly trashed Dostoevsky (called him a "cheap sensationalist"), mocked Faulkner, and had zero patience for any writer he deemed "middlebrow." This attitude bleeds into his novels. There’s a certain "keep up or get out" energy to his writing.

But that’s actually a sign of respect for the reader. He assumes you’re smart. He assumes you’re paying attention. He doesn't spoon-feed you emotions or plot points. He invites you to be an active participant in the creation of the story.

When you finally "get" a joke in The Gift or realize the true identity of a character in The Real Life of Sebastian Knight, it feels like a genuine achievement. You aren't just consuming content; you’re engaging with a mind that is operating at 100% capacity.

Practical steps for getting into Nabokov

If you’re ready to actually dive into the novels of Vladimir Nabokov, don't just grab the first thing you see. You need a game plan so you don't get discouraged.

- Start with Pnin. It’s short, it’s funny, and it shows his heart. It’ll prove to you that he’s not just a cold stylist.

- Read Lolita, but read the introduction by Alfred Appel Jr. if you can find it. It helps to have the context of the "literary game" he’s playing.

- Don't worry about the French. Nabokov loved to drop French phrases into his English books. Just keep reading. Usually, the meaning is clear from the context, or it’s just flavor. Don't let it stop your momentum.

- Pay attention to the colors. Nabokov had synesthesia—he literally "saw" letters as colors. When he describes a sunset or a room, he’s being incredibly specific about the palette. Try to visualize it exactly as he describes it.

- Listen to his lectures. If you want to understand his philosophy, check out his Lectures on Literature. Hearing him rip apart Madame Bovary or The Metamorphosis will give you a huge insight into what he’s trying to do in his own fiction.

Nabokov’s work isn't a mountain to be climbed; it’s a garden to be explored. There are no right or wrong answers, only the "aesthetic bliss" he so famously chased. Stop worrying about the "classics" status and just enjoy the words. They’re some of the best ever written.

To truly experience his range, pick up a copy of The Stories of Vladimir Nabokov. While his novels get the glory, his short fiction—like Signs and Symbols or The Vane Sisters—contains the exact same DNA in a more concentrated form. These shorter works act as perfect entry points into his obsession with memory, loss, and the "otherworld" that he believed sat just behind the veil of our everyday lives. Once you've spent an afternoon with his short stories, you'll find the transition to his more complex novels feels much more natural.