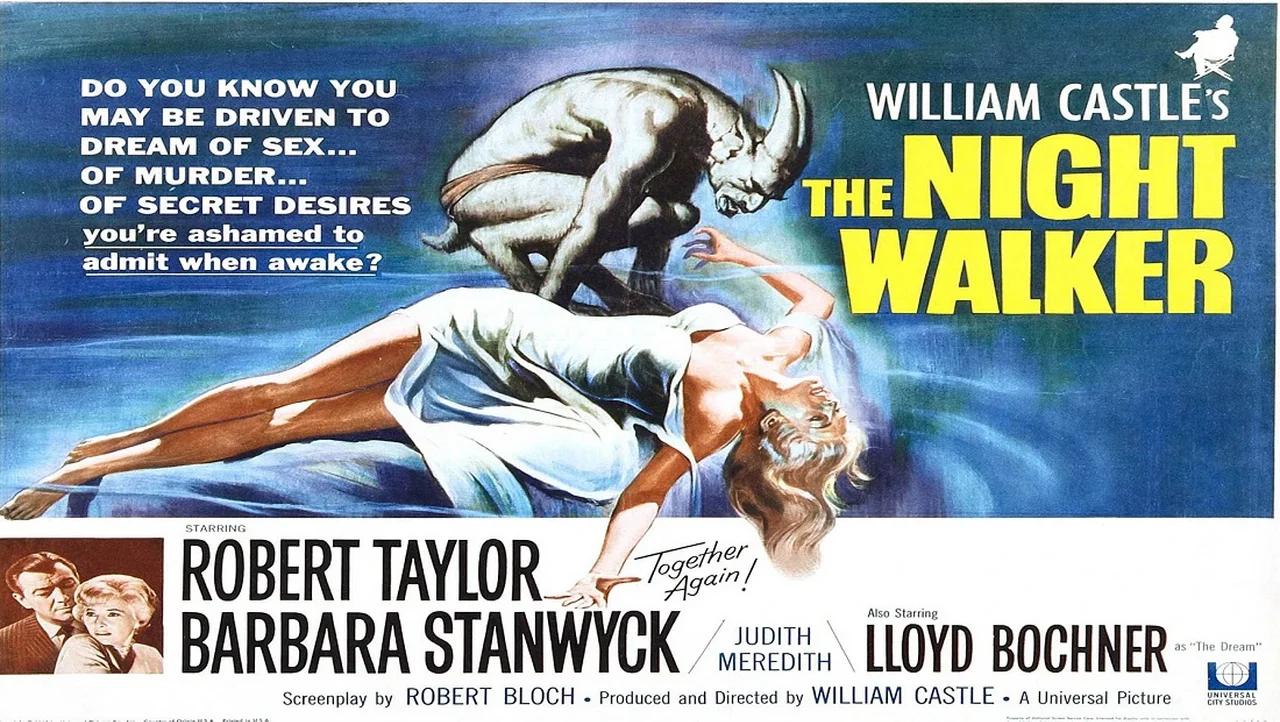

William Castle was known for being a bit of a gimmick king. If you went to see one of his movies in the fifties or sixties, you might find yourself sitting in a chair wired to vibrate, or you’d see a plastic skeleton flying over your head on a wire. But when he made The Night Walker 1964, he dialed back the carnival tricks and leaned into something way more unsettling: the blurred line between dreams and reality.

It’s a strange movie. Seriously.

The plot basically centers on Irene Trent, played by the legendary Barbara Stanwyck in her final big-screen role. She’s trapped in a nightmare of a marriage to a blind, insanely jealous man named Howard. He thinks she’s cheating on him with a "dream lover." Then, Howard dies in a massive laboratory explosion—which is a very 1960s way to go—and Irene thinks she’s finally free.

Except she isn't.

She starts having these incredibly vivid, terrifying dreams where her husband comes back, or she’s led through a wax museum of wedding guests. It’s trippy. It’s grainy. It feels like a fever dream because Castle, working with a script by Robert Bloch (the guy who wrote the novel Psycho), wanted to mess with your head rather than just jump-scare you.

The Bloch-Castle Connection That Made The Night Walker 1964 Work

You can’t talk about this film without talking about Robert Bloch. After Psycho became a cultural phenomenon, everyone wanted a piece of his brain. When he teamed up with Castle for The Night Walker 1964, he brought that signature "nothing is what it seems" energy.

🔗 Read more: Anjelica Huston in The Addams Family: What You Didn't Know About Morticia

The dialogue isn't always natural. It’s stylized. It feels like a noir film that took a wrong turn into a twilight zone. Robert Taylor, who was actually Stanwyck's ex-husband in real life, plays her lawyer and confidant, Barry Moreland. There’s an undeniable, slightly uncomfortable chemistry there. You're watching two people who were once married in reality, playing characters who are trying to figure out if they can trust each other in a world of ghosts and shadows.

Castle didn't use "Emergo" or "Percepto" here. He didn't need to. He used the psychological weight of the actors and Bloch’s twisty narrative. Most people expected a slasher or a monster movie, but what they got was a proto-slasher psychological mystery that feels like a bridge between the Universal Monsters era and the "giallo" films that would soon come out of Italy.

Why the Dream Logic Still Holds Up

If you watch The Night Walker 1964 today, the first thing you'll notice is the sound design. The "dream" sequences use this echoey, metallic reverb that makes everything feel hollow and wrong.

Irene walks through her old house, and the doors open by themselves. She meets a mysterious, handsome man who may or may not be a figment of her imagination. The wax figures are the real stars, though. There is something inherently primal about the fear of mannequins or wax statues. Castle leans into that "uncanny valley" effect long before we had a name for it.

The movie asks a question that resonates even now: How do you prove you aren't crazy when your own senses are lying to you?

💡 You might also like: Isaiah Washington Movies and Shows: Why the Star Still Matters

Critics at the time were kind of mixed on it. Some felt it was too slow. Others thought the "twist" was a bit telegraphed. But looking back, the film's DNA is all over modern psychological horror. You see flashes of it in things like Inception or even the more surreal moments of A Nightmare on Elm Street. It’s about the vulnerability of sleep.

Key Elements of the Production

- The Cast: Barbara Stanwyck, Robert Taylor, Judi Meredith, and Hayden Rorke.

- The Script: Robert Bloch’s influence is everywhere, especially in the "mommy issues" and the obsession with taxidermy or statues.

- The Score: Vic Mizzy, the man who did the Addams Family theme, did the music here. It’s haunting but has that mid-60s orchestral swell.

- The Cinematography: Shot in black and white by Harold Stine, which was a deliberate choice to keep the "noirish" feel even though color was the standard by 1964.

Misconceptions About the Ending

A lot of people remember The Night Walker 1964 as a supernatural ghost story. If you haven't seen it in twenty years, that's probably how it lives in your head.

But it’s not.

Without spoiling the entire climax for the three people who haven't seen it, the movie is firmly rooted in human greed and gaslighting. It’s much more grounded than a haunting. It’s about people using technology and psychology to drive someone to the brink of insanity. In that sense, it’s actually more terrifying than a ghost story because people are capable of much worse things than spirits are.

Some fans argue that the "rational" explanation actually ruins the vibe established in the first hour. I get that. There’s a segment of horror fans who prefer the dreamworld to stay weird. But Castle was a showman; he wanted a resolution that the audience could chew on while they walked to their cars.

📖 Related: Temuera Morrison as Boba Fett: Why Fans Are Still Divided Over the Daimyo of Tatooine

Actionable Insights for Horror Fans and Collectors

If you're looking to dive into this era of cinema or specifically want to track down The Night Walker 1964, here is how to get the most out of the experience.

Watch the "Psychology of Dreams" Intro

Originally, the film had a prologue featuring a narrator (often Vic Perrin) talking about the nature of dreams. If you find a version that includes this, watch it. It sets the "pseudo-science" tone that was popular in the 60s and makes the whole experience feel like a weird laboratory experiment.

Look for the Shout! Factory Blu-ray

Don't settle for a grainy YouTube upload. The black-and-white cinematography in this film relies heavily on "crushed blacks" and shadows. A high-definition restoration is the only way to see the detail in the wax museum scenes, which are arguably the best parts of the movie.

Double-Feature Recommendation

To really see Robert Bloch’s range, watch this back-to-back with Strait-Jacket (also 1964). Both films deal with older Hollywood actresses (Stanwyck in one, Joan Crawford in the other) being pushed to the edge of sanity. It’s a fascinating look at how the industry viewed aging starlets during the "Psycho-biddy" subgenre craze.

Pay Attention to the Set Design

The house in the film is basically a character. Notice how the architecture changes between the "real" scenes and the "dream" scenes. The angles get slightly sharper, and the rooms feel larger and emptier. It’s a subtle trick that keeps the viewer off-balance.

Research the Stanwyck-Taylor History

Understanding that the lead actors were a divorced couple adds a massive layer of subtext to their scenes. Their real-life history brings a weariness and a familiarity to the screen that you just can't fake with two strangers.

Ultimately, The Night Walker 1964 stands as a testament to a time when Hollywood was transitioning. It wasn't quite the "Golden Age" anymore, and the gritty "New Hollywood" of the 70s hadn't arrived yet. It exists in this beautiful, spooky limbo. It’s a movie that rewards people who pay attention to the atmosphere rather than just the plot. If you want a film that feels like a rainy midnight in a house you don't recognize, this is the one.