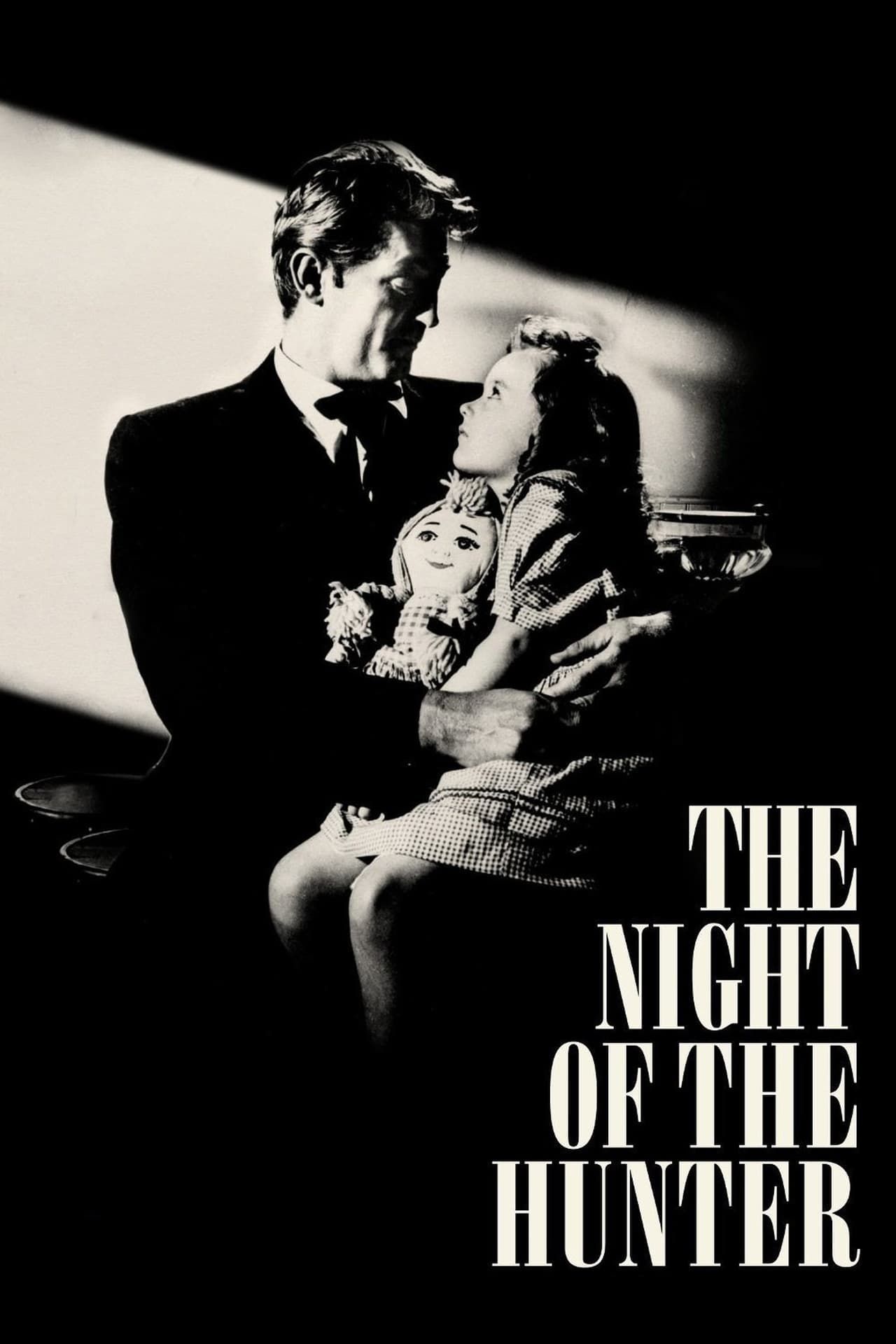

Charles Laughton only directed one movie. Just one. Imagine hitting a grand slam your first time at bat and then never picking up the wood again because the crowd hissed at you. That’s basically what happened with The Night of the Hunter 1955, a film that was so far ahead of its time it practically lived in a different dimension than other mid-fifties melodramas. When it premiered, critics hated it. They thought it was weird. They thought it was "pretentious."

It bombed. Hard.

But today? It's the blueprint. If you’ve ever seen a movie where a villain has tattoos on their knuckles, or a thriller that uses shadows like they’re physical weapons, you’re looking at the DNA of this 1955 masterpiece. It stars Robert Mitchum as Harry Powell, a "preacher" who is actually a serial killer wandering the Depression-era South. He isn't looking for souls; he's looking for a hidden stash of $10,000. And he’s willing to kill a widow and terrorize two small children to get it.

Honestly, it’s a miracle this movie even got made in the Hays Code era. It’s dark. It’s surreal. It feels like a Grimm’s fairy tale told by someone who hasn't slept in four days.

The Preacher With The Knuckle Tattoos

Robert Mitchum was always a cool customer, but in The Night of the Hunter 1955, he is genuinely terrifying. He plays Harry Powell with this oily, narcissistic charm that makes your skin crawl. You know the famous "Love" and "Hate" tattoos across his fingers? That started here.

There’s this incredible scene where he explains the "story of right hand and left hand" to a bunch of townspeople. It’s a performance within a performance. He uses religion as a cloak for his psychopathy, which was a pretty bold move for a 1955 production. James Agee, the legendary critic who wrote the screenplay, pulled this straight from Davis Grubb’s novel, and Mitchum leaned into it with everything he had.

📖 Related: Big Brother 27 Morgan: What Really Happened Behind the Scenes

He’s not a slasher villain. He’s a shark. He moves slowly, singing that eerie "Leaning on the Everlasting Arms" hymn in a baritone that sounds like it's coming from the bottom of a well. When he finally starts chasing the kids, John and Pearl, he doesn't run. He just walks. Because he knows they have nowhere to go.

A Visual Style That Shouldn't Exist

If you pause this movie at any random second, you’re looking at a painting. Stanley Cortez, the cinematographer, used "German Expressionism" techniques. That sounds fancy, but it basically means using high-contrast lighting—pitch black shadows and blinding whites—to show how a character feels inside.

Think about the bedroom scene. Powell stands over Shelley Winters’ character, Willa, in a room that looks like a cathedral. The ceiling comes to a sharp, aggressive point. The light falls in bars like a cage. It doesn't look like a real house in West Virginia. It looks like a nightmare. Laughton didn't care about realism. He wanted "filmic truth," which is a whole different beast.

There is one shot that people still talk about in film schools today: a car at the bottom of a river. I won't spoil the exact visual for you if you haven't seen it, but it involves a woman’s hair flowing like seaweed in the current. It is hauntingly beautiful and deeply disturbing.

Why Audiences in 1955 Just Didn't Get It

People were used to Westerns and straightforward noir. They wanted Gene Kelly dancing or John Wayne shooting things. They didn't want a surrealist fable about a man of God hunting children through a swamp.

👉 See also: The Lil Wayne Tracklist for Tha Carter 3: What Most People Get Wrong

The tonal shifts are wild. One minute it’s a gritty crime drama, the next it’s a literal fairy tale where the children are floating down a river in a skiff, surrounded by oversized frogs and spiders. It’s lyrical. It’s poetic. It’s also deeply cynical about how easily "good" people can be fooled by a charismatic liar.

Laughton was heartbroken by the failure. He never directed again. It’s one of the great tragedies of cinema history because he clearly had a vision that was thirty years ahead of the curve. Critics like Pauline Kael eventually helped revive its reputation, but by then, Laughton was long gone.

The Lillian Gish Factor

In the second half of the film, we meet Rachel Cooper, played by the silent film legend Lillian Gish. If Powell represents the "Hate" tattooed on his left hand, Rachel is the "Love" on the right. She’s a tough-as-nails woman who takes in waifs and strays.

The standoff between Gish and Mitchum is the emotional peak of the film. She sits on her porch with a shotgun across her lap, watching the silhouette of the Preacher at the edge of her property. They end up singing a duet. It’s one of the tensest scenes in movie history, and neither person even raises their voice.

It proves that you don't need jump scares or CGI to create atmosphere. You just need a shotgun, a hymn, and a man in a black hat sitting on a horse in the moonlight.

✨ Don't miss: Songs by Tyler Childers: What Most People Get Wrong

The Lasting Legacy of Night of the Hunter 1955

You can see the influence of this movie everywhere. Spike Lee directly paid homage to the "Love/Hate" tattoos in Do the Right Thing. The Coen Brothers have practically built a career on the kind of southern-gothic weirdness that Laughton pioneered here.

Even the way we think about "creepy" music in horror owes a debt to this film’s score. Walter Schumann’s music shifts from lullabies to jarring, dissonant brass hits that tell the audience exactly when the monster is close.

The Night of the Hunter 1955 is a movie about the loss of innocence, but it’s also about the resilience of children. John, the young boy, is the only one who sees Powell for what he is from the very beginning. The adults are all blinded by Powell’s "piety," but the kid knows. He’s the moral center of a world that has gone completely insane.

Practical Steps for First-Time Viewers

If you're going to watch this, don't treat it like a boring "classic." Treat it like a psychological thriller.

- Watch the Criterion Collection version: The restoration is incredible. The blacks are deep, and the whites pop. If you watch a grainy YouTube rip, you’re missing half the movie.

- Pay attention to the animals: During the river sequence, Laughton uses close-ups of animals (toads, owls, turtles). They aren't just there for scenery; they represent the indifference of nature to the kids' suffering.

- Look at the shadows: Notice how the shadows of the window frames often look like crosses or cages. It’s intentional.

- Listen to the wind: The sound design is surprisingly sophisticated for 1955.

Next time you’re scrolling through a streaming service and everything looks like a glossy, over-lit TV show, go back to this. It’s a reminder that movies can be strange, beautiful, and terrifying all at once. It’s a one-of-a-kind freak of cinema that we’re lucky to have.

To truly appreciate the craft, look for the documentary Charles Laughton Directs The Night of the Hunter. It features outtakes that show how Laughton worked with the actors—often being quite harsh to get those raw, terrified performances out of the kids. It adds a whole new layer of grit to the experience.

Actionable Insights:

- Source the Right Cut: Seek out the 4K or Blu-ray restoration to appreciate Stanley Cortez's high-contrast cinematography, which is the film's primary storytelling tool.

- Contextualize the Villain: Research the real-life inspiration for Harry Powell—serial killer Harry Powers—to see how Laughton turned a true-crime story into a dark fable.

- Analyze the Silhouette: Pay close attention to the use of silhouettes in the "river journey" segment; this technique influenced modern directors like Guillermo del Toro and David Lynch.

- Compare Tones: Contrast the first half's noir-style tension with the second half's pastoral, "fairytale" atmosphere to understand why the film confused 1950s audiences.