Albert Finney had just become a global superstar through Tom Jones. He was the "angry young man" of British cinema, a face that defined the grit and sweat of the 1960s. So, when he decided to tackle a remake of a 1930s stage classic, people expected something polished. Instead, they got Danny. The Night Must Fall movie 1964 isn't just a remake; it’s a total psychological demolition of its source material.

Honestly, most people who love classic thrillers point toward the 1937 version starring Robert Montgomery. That one is theatrical, charming, and safe. But the 1964 reimagining? It’s sweaty. It’s claustrophobic. It feels like a fever dream that won't break. While the original relied on the "polite" suspense of the era, director Karel Reisz decided to lean into the burgeoning "Kitchen Sink" realism movement, turning a drawing-room mystery into a jarring study of a sociopath.

The Plot That Still Gets Under Your Skin

The setup seems simple enough. We are in a rural English estate. Mrs. Bramson (played by the legendary Sheila Hancock) is a wealthy, demanding, and largely unbearable woman who lives with her niece, Olivia. Enter Danny. Danny is a bellhop from a local hotel who has gotten a local girl pregnant. He arrives at the house to "face the music," but within minutes, he has charmed his way into Mrs. Bramson’s good graces.

He becomes her favorite. Her "pet."

But Danny is carrying a hatbox. This isn't a spoiler for a sixty-year-old movie: the hatbox contains a human head. The Night Must Fall movie 1964 doesn't try to hide the fact that Danny is a killer. The tension doesn't come from if he did it, but from when he will do it again. It’s a masterclass in dramatic irony that makes your skin crawl because you’re watching this woman invite her own executioner to stay for tea.

Why This Version Divides Horror Fans

Most remakes fail because they try to replicate the original’s magic. Reisz didn't care about that. He wanted to make something modern. By 1964, the world had seen Psycho. We knew what a "mommy’s boy" killer looked like.

Finney’s performance is polarizing. Some critics at the time found it too "on the nose," but if you watch it today, it’s terrifyingly accurate to how modern narcissists operate. He uses his charm like a blunt instrument. He’s not subtle. He’s performing for an audience of one at all times.

The cinematography by Freddie Francis (the guy who later won Oscars for Glory and Sons and Lovers) is what really carries the weight here. He uses deep shadows and weirdly close angles that make the house feel like it’s shrinking around the characters. It’s a visual representation of a trap.

✨ Don't miss: Austin & Ally Maddie Ziegler Episode: What Really Happened in Homework & Hidden Talents

The Problem With the Script

If there’s a weakness, it’s that the movie tries a bit too hard to be "new." The original play by Emlyn Williams was a tight, three-act thriller. This 1964 version wanders. It takes its time. It wants you to feel the boredom of the countryside before the violence hits. Some viewers find the pacing a bit sluggish, especially in the second act. But for me? That slow burn is exactly what makes the ending hit like a freight train.

You’ve got to remember that in 1964, British cinema was transitioning. We were moving away from the "stiff upper lip" mysteries of Agatha Christie and into the raw, sexualized, and violent world of the late 60s. This movie sits right on that uncomfortable fence.

Karel Reisz and the New Wave Influence

Karel Reisz was a founder of the Free Cinema movement. He liked reality. He liked dirt. When he took on the Night Must Fall movie 1964, he stripped away the stagey artifice.

In the 1937 version, the setting is a cozy cottage. In 1964, it’s a cold, imposing manor. The change is significant. It moves the story from a "whodunnit" vibe to a "Gothic horror" vibe. Reisz focuses on the psychological obsession Olivia has with Danny. She suspects he’s a monster, yet she’s attracted to him. It’s a dark, messy dynamic that the 30s version couldn't touch because of the Hays Code.

- Danny (Albert Finney): Charismatic, erratic, and deeply broken.

- Mrs. Bramson (Mona Washbourne): Needy and oblivious, representing the dying upper-class ego.

- Olivia (Susan Hampshire): The moral compass that is spinning wildly out of control.

It’s the performances that keep this movie relevant. Mona Washbourne is particularly incredible. She plays the "invalid" who is actually just bored and selfish, making you almost—almost—understand why someone would want to get rid of her.

What Most People Get Wrong About the 1964 Remake

Commonly, people dismiss this as a "failed experiment." They say it didn't capture the charm of the original. That's actually the point. It wasn't trying to be charming. It was trying to be ugly.

If you go into this expecting a fun night of 60s nostalgia, you’re going to be disappointed. It’s a bleak film. It deals with class resentment, sexual repression, and the sheer randomness of psychopathic violence. People often forget that Albert Finney produced this himself. He wanted to play a villain. He wanted to prove he could be more than just the lovable rogue.

🔗 Read more: Kiss My Eyes and Lay Me to Sleep: The Dark Folklore of a Viral Lullaby

The most misunderstood element is the "head in the hatbox" trope. By 1964, this was already a cliché. Reisz uses it as a symbol of the secrets we carry in plain sight. Danny carries his "guilt" and his "trophy" around with him, and the people around him are too polite—or too self-absorbed—to look inside.

The Sound of Terror

One thing that really stands out is the sound design. Or rather, the lack of it. There are long stretches of silence where all you hear is the wind or a ticking clock. It builds an unbearable level of anxiety. When the music does kick in, it’s discordant. It doesn't tell you how to feel; it just makes you feel uncomfortable.

Compare this to the 1937 version, which had a very traditional, sweeping score. The Night Must Fall movie 1964 feels modern because it understands that silence is often scarier than a loud orchestra.

Tracking the Legacy: Why You Should Care Now

We live in an era of "elevated horror" and true crime obsession. Movies like Saltburn or The Talented Mr. Ripley owe a huge debt to the way this film handles the "invader" archetype. Danny is the original "pretty boy" killer who uses his class status (or lack thereof) to manipulate those around him.

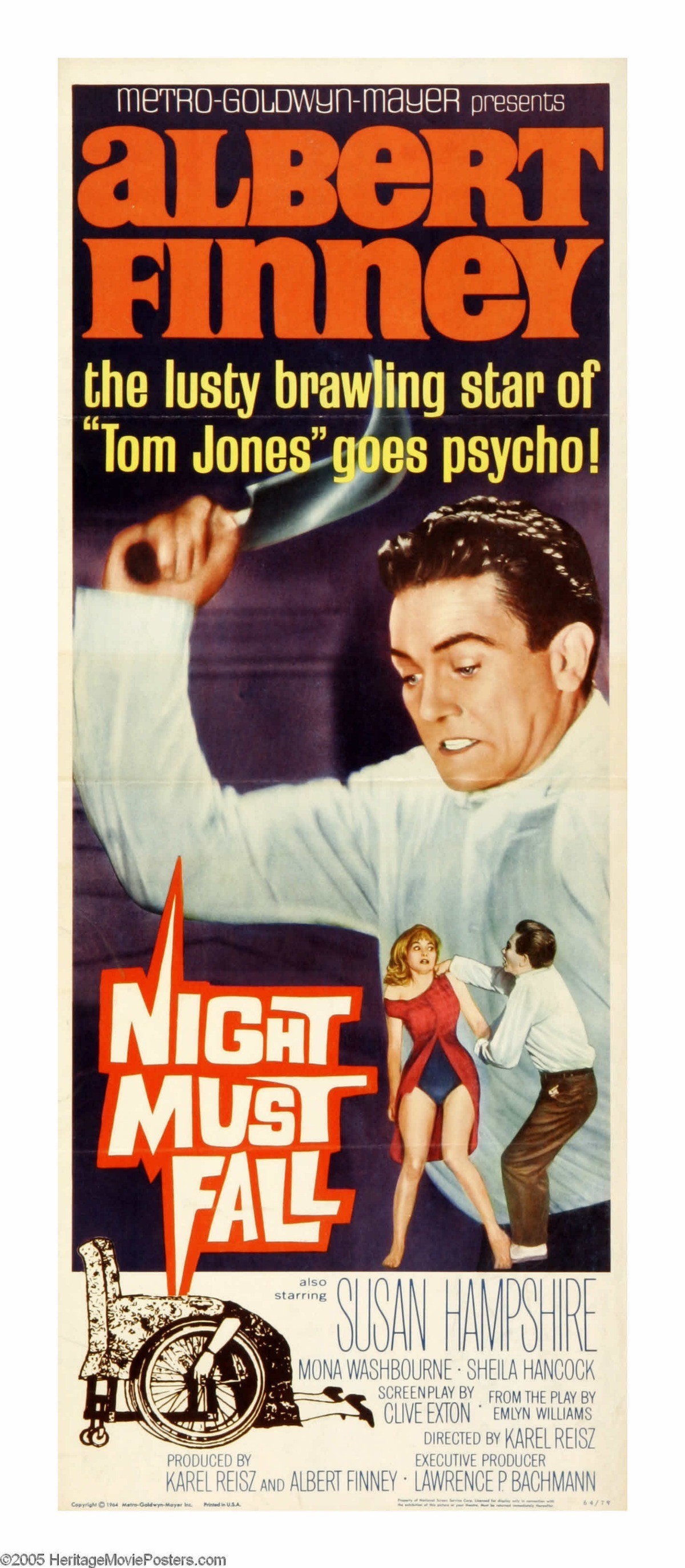

The film didn't do great at the box office when it was released. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer didn't really know how to market it. Was it a horror movie? A drama? A remake? They settled on a weird middle ground that confused everyone.

Today, we can see it for what it is: a bridge between the Golden Age of Hollywood and the New Hollywood of the 1970s. It’s a fascinating artifact for anyone interested in how cinema evolved.

How to Watch It Today

Finding a high-quality version of the Night Must Fall movie 1964 can be a bit of a hunt. It isn't always on the major streaming platforms like Netflix or Max. Usually, you have to look toward specialty sites like the Criterion Channel or Turner Classic Movies (TCM).

💡 You might also like: Kate Moss Family Guy: What Most People Get Wrong About That Cutaway

If you do find it, watch it back-to-back with the 1937 version. It’s the best way to see how much the world changed in twenty-seven years. The dialogue is mostly the same, but the soul of the story is completely different.

- Check TCM's Schedule: They rotate it frequently during "British Cinema" months.

- Look for the Warner Archive DVD: It’s the most consistent way to get a decent transfer.

- Watch the shadows: Pay attention to how the lighting changes as Danny's mental state deteriorates.

Final Takeaway on the 1964 Version

Is it a "perfect" movie? No. It’s messy and sometimes pretentious. But it’s a much more honest exploration of a killer’s mind than the original version. Finney’s performance is a powerhouse of 60s energy, and the direction is bold enough to be genuinely unsettling even sixty years later.

If you want a movie that will stay with you—the kind that makes you look twice at the box someone is carrying—this is it. It’s a grim, fascinating look at the darkness that hides behind a smile.

To truly appreciate this film, you need to step away from the idea of a "cozy mystery." This is a psychological thriller in the truest sense. For the best experience, watch it late at night with the lights low. Just make sure the doors are locked and you know exactly what’s in your own storage boxes.

Next Steps for Film Lovers

To get the most out of your screening, compare the 1964 film's ending to the original stage play's climax. The film takes a more visceral approach that was considered quite shocking for its time. You might also want to look up Karel Reisz's other work, specifically Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, to see how he brought that same "angry young man" energy to different genres. Understanding the British New Wave context will make Danny's outbursts feel much more like a social commentary than just a horror trope.