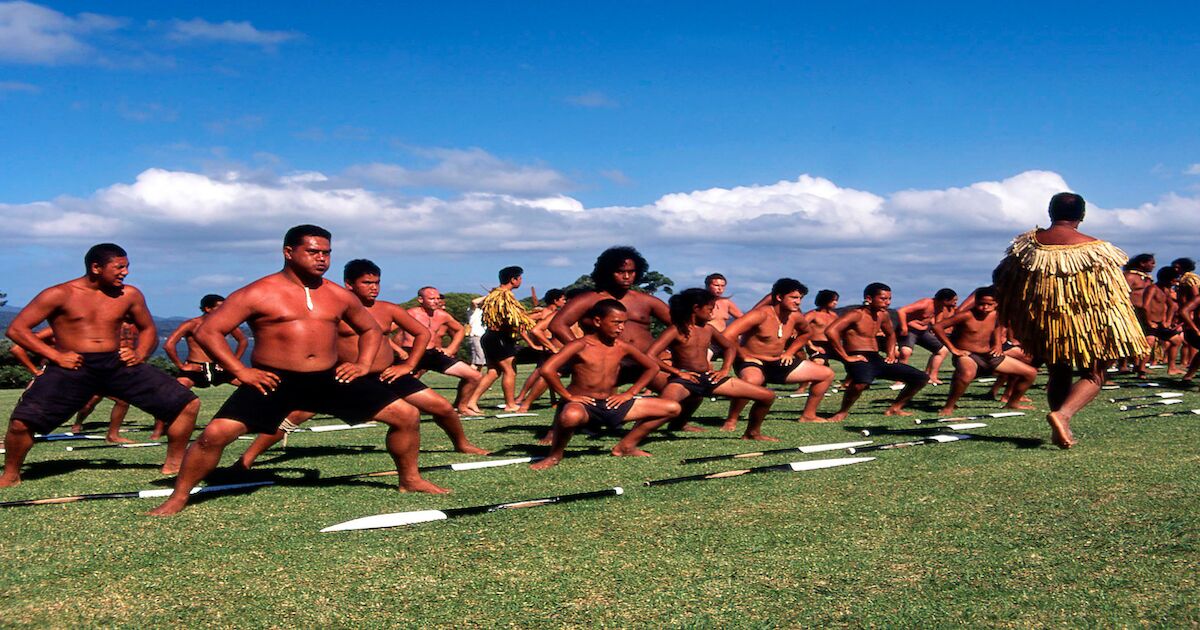

It starts with a silence so thick you could cut it with a knife. Then, a roar. Tens of thousands of fans in a stadium like Eden Park or Twickenham suddenly go quiet because they know what's coming. One man steps forward. He screams a challenge that echoes off the rafters, and suddenly, fifteen giants are slapping their thighs and chests in a terrifying, rhythmic unison.

If you’ve watched rugby, you’ve seen the New Zealand All Black haka dance. It’s the most iconic image in international sports. But honestly? Most people outside of Aotearoa (that’s the Māori name for New Zealand) kind of fundamentally misunderstand what they’re looking at. They think it’s just a "war dance" meant to scare the other team. Sure, that’s a part of it. But if you think it’s just about intimidation, you're missing the entire soul of the thing.

The haka is a bridge. It’s a connection to ancestors, a statement of identity, and a very literal way of grounding yourself before a storm.

The two faces of the New Zealand All Black haka dance

For decades, the world only really knew one version: Ka Mate. It’s the one about the hairy man who brought the sun. It was composed by Te Rauparaha, a chief of the Ngāti Toa tribe, around 1820. The story goes that he was hiding in a kūmara (sweet potato) pit from his enemies, and when he climbed out, he saw the sunlight and a friendly chief. "It is life! It is life!" he shouted.

But things changed in 2005.

Before a massive Tri-Nations match against South Africa in Dunedin, the All Blacks debuted Kapa o Pango. This wasn't a borrowed piece of history; it was written specifically for the team by Derek Lardelli, a master of Māori arts. While Ka Mate is legendary, Kapa o Pango is personal. It talks about the silver fern. It talks about the land. It ends with a thumb-across-the-throat gesture that caused a massive stir in the media back in the day. Critics called it violent. The players? They said it was about drawing "hauora"—the breath of life—into the body.

Basically, the All Blacks now have a choice. Depending on the gravity of the match or the location, they pick the one that fits the "vibe."

📖 Related: Bethany Hamilton and the Shark: What Really Happened That Morning

Is it actually an unfair advantage?

Every few years, someone in the sports media world gets annoyed. They claim the New Zealand All Black haka dance gives the Kiwis a psychological edge that other teams shouldn't have to deal with. They argue that while the All Blacks are getting their adrenaline peaking, the opposition has to stand there like statues, getting cold and intimidated.

Honestly, it’s a bit of a reach.

Look at the history of how teams respond. In 1989, the Irish captain Willie Anderson led his team forward until they were nose-to-nose with the All Blacks. It was legendary. In 2007, France stood in a line wearing tricolor flags and stared them down from two feet away. Then you had the 2019 Rugby World Cup, where England formed a "V" formation to surround the haka. They got fined for crossing the halfway line, but they won the game.

The reality? The haka doesn't win games. The All Blacks win games because their grassroots system is a machine. But the haka does set a standard. If you're wearing that black jersey, you aren't just playing for yourself. You're playing for every person who did that dance before you. That’s a lot of weight to carry.

Why the feet matter more than the hands

If you watch a professional kapa haka performer, they’ll tell you the power comes from the legs. It’s called whitiwhiti kōrero. The feet stay heavy. They stamp. This isn't ballet; it's about being "papatūānuku"—connected to the earth.

When you see a player like TJ Perenara or Aaron Smith leading the New Zealand All Black haka dance, look at their eyes. That bulging eye look? That’s pūkana. It’s not just a "scary face." It’s a way of showing intensity and passion. It’s meant to show that you are fully present. No distractions. No fear. Just the moment.

👉 See also: Simona Halep and the Reality of Tennis Player Breast Reduction

The evolution of "The Haka" in the professional era

There was a time, believe it or not, when the All Blacks were actually kind of bad at the haka. In the 1970s and early 80s, footage shows them sort of hopping around awkwardly. It looked more like a line dance at a wedding than a fierce cultural challenge. The non-Māori players didn't really know the movements, and there wasn't a huge emphasis on getting it "right."

That changed in the late 80s with Buck Shelford.

Shelford, a hard-as-nails No. 8 with deep Māori roots, insisted that if they were going to do it, they were going to do it properly. He made the team practice. He taught them the meaning of the words. He turned it into a weapon of unity. Since then, the team has employed cultural advisors like Te Wehi Wright to ensure that every finger flick and every foot stomp is culturally accurate. It’s no longer a performance; it’s a discipline.

Acknowledging the controversy

We have to be real here: the haka in sports isn't without its critics within the Māori community too. Some feel that seeing a sacred cultural practice used to sell Adidas jerseys and Gatorade is a bit... off. It's called "commodity fetishism" in academic circles.

However, the general consensus in New Zealand has shifted toward pride. Most see the New Zealand All Black haka dance as a vehicle for Māori culture to occupy center stage in a world that often tries to sideline indigenous voices. When the All Blacks do the haka in front of 80,000 people in Paris or London, they are forcing the world to acknowledge Māori language and sovereignty. That’s a powerful thing.

What you should look for next time

Next time you see the All Blacks line up, don't just look at the guy in the front. Watch the guys in the back. Watch the new players. You can see the sheer terror and pride in their faces. It’s their "coming of age."

✨ Don't miss: NFL Pick 'em Predictions: Why You're Probably Overthinking the Divisional Round

- The Leader: Usually someone with Māori lineage, but not always. It’s about who has the "mana" (prestige/power) to lead the group.

- The Response: See how the other team reacts. Do they retreat? Do they advance? This "war of nerves" is often more interesting than the dance itself.

- The Silence: The moment after the haka is the loudest. The crowd erupts, and the energy in the stadium shifts instantly.

How to respect the tradition as a fan

If you're ever lucky enough to be at a game, there are a few "unwritten rules" for watching the New Zealand All Black haka dance.

- Don't whistle or boo. In some cultures, whistling is cheering. In New Zealand, whistling during a haka is seen as a massive sign of disrespect.

- Watch the whole thing. Don't head to the bar or the bathroom. You're watching a living piece of history.

- Understand the "why." It’s not just for the fans. It’s for the players to find their "inner taniwha" (monster/spirit).

The New Zealand All Black haka dance is a rare thing in modern, sanitized professional sports. It’s raw. It’s messy. It’s loud. It’s one of the few times you see professional athletes show genuine, unscripted emotion before the whistle even blows. It reminds us that sports aren't just about stats or contracts. They're about where we come from.

To truly appreciate the haka, you have to look past the theatricality. It’s a heartbeat. When those fifteen men move as one, they aren't just a rugby team anymore. They're a representation of a tiny island nation at the bottom of the world, telling the rest of the planet: "We are here. We are strong. And you're going to have to go through us."

Moving forward with the Haka

If you want to understand the cultural mechanics better, look up the work of Dr. Ngāhuia Te Awekōtuku or Peter Sharples. They've spent decades explaining how kapa haka (the broader art form) functions as a tool for social cohesion.

For the casual fan, the best way to honor the tradition is simple: learn the words to Ka Mate. Understanding that the "Hairy Man" who fetched the sun is a metaphor for overcoming adversity changes how you hear the chant. It stops being noise and starts being a story. One of survival. One of life.

Watch the feet. Hear the breath. Respect the silence. That’s how you watch a haka.