It’s April 30, 1939. You’re standing in a swamp in Queens that used to be a literal ash dump—the one F. Scott Fitzgerald called a "valley of ashes" in The Great Gatsby. But the smell of garbage is gone. Instead, there’s this massive, blindingly white spike hitting 700 feet in the air and a giant ball next to it. They called them the Trylon and the Perisphere. For a couple of bucks, you weren't just visiting a park; you were stepping into "The World of Tomorrow."

The New York World's Fair 1939 wasn't just some corporate trade show. It was a massive, desperate, beautiful attempt to convince a generation scarred by the Great Depression that the future wouldn't actually suck.

Honestly, we’re still living in the shadow of that fair. When you look at how we design cities or why we’re obsessed with the "smart home," you can trace the DNA right back to those 1,200 acres in Flushing Meadows. It’s kinda wild how much they got right, and even weirder how much they got wrong.

The Futurama: When GM Invented the American Suburb

If you wanted to see the biggest hit of the fair, you had to wait in line for hours at the General Electric or General Motors pavilions. But GM’s "Futurama" was the real MVP. Designed by Norman Bel Geddes, it was basically a ride where you sat in moving chairs and looked down at a massive scale model of the United States in 1960.

Imagine seeing 50,000 miniature cars on automated highways. Back then, most of America was still dirt roads and rural farms. People walked out of that exhibit with a "carry-home" pin that said, "I have seen the future." And they believed it. Bel Geddes wasn't just dreaming; he was pitching a lifestyle. He showed them high-speed expressways bypassing cities, which basically became the blueprint for the Interstate Highway System we use today.

💡 You might also like: Different Kinds of Dreads: What Your Stylist Probably Won't Tell You

It's sorta fascinating because the fair sold the car as the ultimate tool of freedom. They didn't mention the traffic jams or the way those highways would eventually tear apart urban neighborhoods. They just showed the shiny, streamlined perfection of it all.

Not Just Shiny Gadgets: The Politics of 1939

While everyone was staring at the "Elektro the Moto-Man"—a seven-foot-tall robot that could smoke cigarettes (yes, really)—the real world was falling apart. The New York World's Fair 1939 opened just months before Germany invaded Poland.

There was a massive "League of Nations" building and a "Peace and Freedom" area. But the tension was thick. The Czechoslovakian pavilion ended up being funded by personal donations because, by the time the fair was in full swing, their country had already been occupied by the Nazis. The USSR had a massive pavilion with a statue of a worker holding a star, which was eventually torn down when the fair moved into its second season in 1940 because, well, the political climate had shifted "just a bit."

The "Town of Tomorrow" and the Birth of the Kitchen Gadget

If you go to a tech convention now, you see VR headsets. In 1939, people were losing their minds over the "Dishwasher."

📖 Related: Desi Bazar Desi Kitchen: Why Your Local Grocer is Actually the Best Place to Eat

The Fair had a section called the Town of Tomorrow. It featured fifteen demonstration homes. This is where the American obsession with the "modern kitchen" started. They showcased things like:

- Fluorescent lighting (which looked like alien tech at the time).

- The first public demonstration of television by RCA. David Sarnoff stood in front of a camera and his image was beamed to receivers a few miles away.

- "Talkies" were old news, but the idea of seeing a person's face while they spoke? Total sci-fi.

- Pre-packaged foods and the rise of the "all-electric" home.

Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz might have popularized the suburban ideal later, but the New York World's Fair 1939 built the set for it. Companies like Westinghouse and Borden (with Elsie the Cow) weren't just selling products; they were selling the idea that technology would do all your chores so you could spend your time... well, they weren't quite sure what you'd do, but it would be glorious.

Why It Ended Up Losing a Fortune

For all its cultural impact, the fair was kind of a financial disaster. It cost about $160 million to build—in 1939 money. That’s billions today.

The planners expected 60 million people. They got about 45 million. Why? Because the world was at war. By the second season in 1940, the theme shifted from "The World of Tomorrow" to "For Peace and Freedom" to try and drum up patriotic support. The whimsical futurism felt a bit hollow when the newsreels were showing London being bombed.

👉 See also: Deg f to deg c: Why We’re Still Doing Mental Math in 2026

When the fair closed in October 1940, they didn't just pack up. They demolished almost everything. The steel from the Trylon and Perisphere was actually melted down to be used for the war effort. It’s a bit poetic, honestly—the symbols of a peaceful future being turned into tanks and ships.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Fair

A lot of folks think the 1939 fair was the one with the Unisphere (that giant metal globe you see in Men in Black). Nope. That was the 1964 World's Fair.

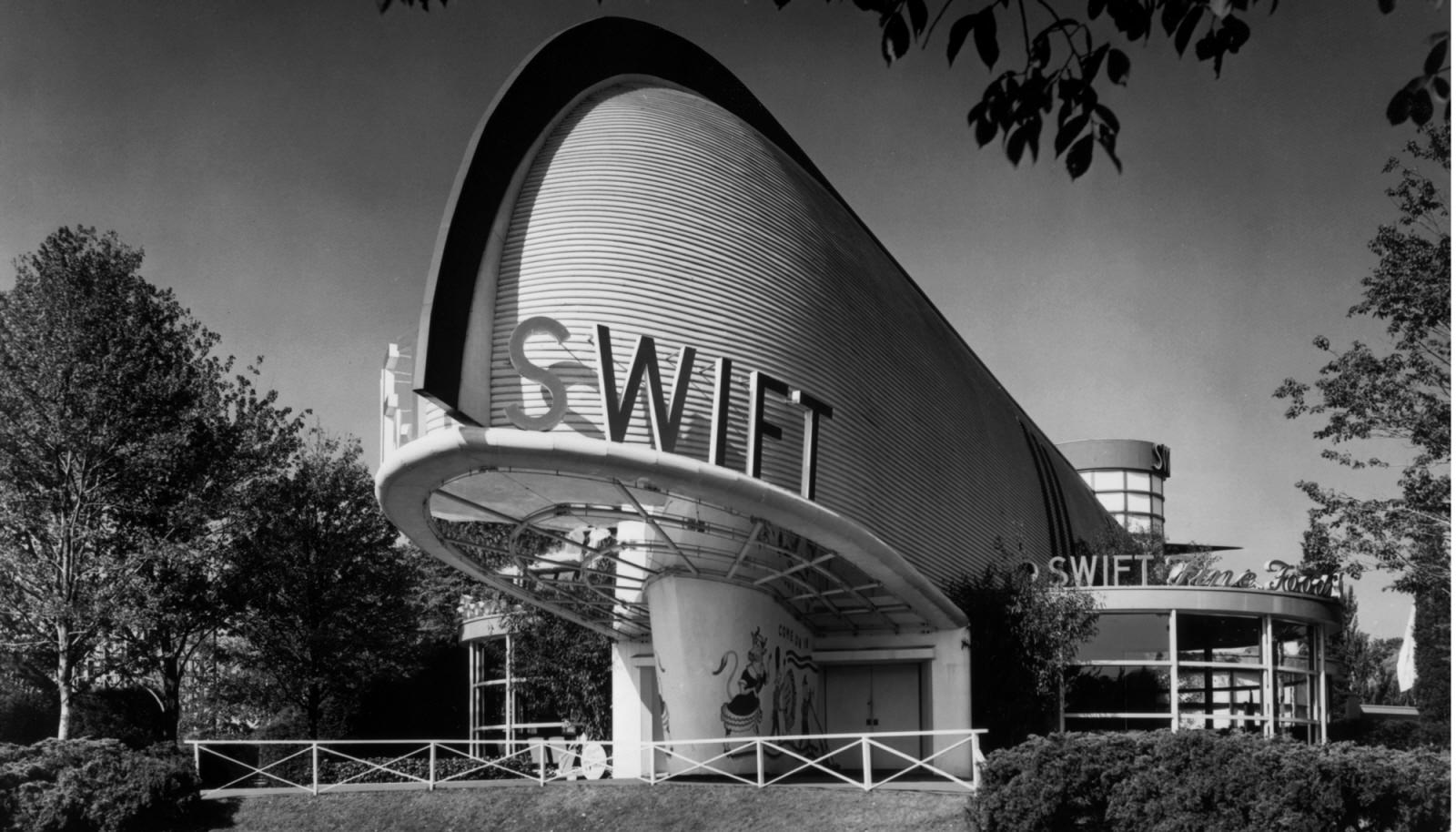

The 1939 fair was much more "Art Deco meets Sci-Fi." It was about streamlining. Everything had to look like it was moving at 100 mph, even if it was a pencil sharpener. This "Streamline Moderne" style defined an entire era of American design. If you've ever looked at a 1940s train or a classic toaster and thought it looked "fast," you’re seeing the influence of the New York World's Fair 1939.

How to Explore the Legacy Today

If you actually want to see where this happened, you have to go to Flushing Meadows-Corona Park in Queens.

- Find the Time Capsule: Westinghouse buried a time capsule to be opened in the year 6939. It contains things like a pack of Camels, a fountain pen, and a newsreel. There’s a marker on the ground where it’s buried.

- The Queens Museum: It’s housed in the New York City Building, which is one of the few structures left from the '39 fair. It has a mind-blowing scale model of the city, though that was updated for '64.

- The Pillars of the World: You can still find scattered remnants, like the underground infrastructure and some of the original statues' pedestals, if you're willing to wander the park with a map from the 30s.

Actionable Insights for History Lovers

If you're looking to dive deeper into the New York World's Fair 1939, don't just read a Wikipedia summary.

- Check out the "Prelinger Archives" online. You can find actual color home movies of people walking through the fair. Seeing the bright oranges and blues of the buildings—which were color-coded by zone—is way different than seeing grainy black-and-white photos.

- Look up the "Interborough Rapid Transit" (IRT) maps from 1939. It shows how the city literally built the subway extensions specifically to feed the fair, a move that permanently changed the geography of Queens.

- Read "Twilight at the World of Tomorrow" by James Mauro. It tracks the fair's creation alongside the rise of the Gestapo in Europe. It’s a great way to understand the cognitive dissonance of the time.

The fair taught us that the future is something you have to design, not just wait for. We might not have the flying cars they promised, but the belief that technology can solve human problems? That started in a Queens ash dump in 1939.