You open up a standard Bible, flip past the Old Testament, and there it is. Matthew. Then Mark. Then Luke and John. It feels like a natural progression, right? Like someone sat down and said, "Okay, let’s put these in the exact order they happened." But honestly, that’s not what happened at all. If you’re looking for a chronological timeline, the New Testament Bible order is going to frustrate you. It’s organized by type and, frankly, by length.

Think about it.

The earliest writings in the New Testament aren't even the Gospels. While Matthew sits at the front of the line, most scholars, including experts like Bruce Metzger or Bart Ehrman, agree that Paul’s letters—specifically 1 Thessalonians—were likely written decades before the first Gospel hit the scene. We’re talking about a gap of maybe twenty years. So why do we read it the way we do?

The logic behind the New Testament Bible order

The current layout isn't random. It’s actually pretty systematic once you see the pattern. It’s grouped into four or five main buckets: the Gospels, the history of the early church (Acts), the letters (Epistles), and then the apocalyptic finale (Revelation).

Most people assume the Gospels are first because they are the "most important." In a theological sense, sure. They tell the story of Jesus. But the early church fathers who finalized the canon—guys like Athanasius in his 367 AD Easter Letter—were looking for a narrative flow. You start with the life of Christ, move to the spread of his message, dive into the instructions for how to live, and end with the future.

The Gospel Quartet

Matthew comes first largely because the early church believed it was the "most Jewish" Gospel. It bridges the gap between the Old and New Testaments perfectly with all those genealogy records. Mark is the shortest and punchiest. Luke is the first half of a two-part history project. Then there’s John. John is the outlier. It’s deeply philosophical and doesn’t follow the "synoptic" (seeing together) vibe of the first three.

If you were to arrange these by when they were actually written, Mark would almost certainly jump to the front of the line. Most modern scholars hold to "Markan Priority," the idea that Matthew and Luke actually used Mark as a source.

The strange case of the Epistles

Now, this is where the New Testament Bible order gets really quirky. Once you get past the book of Acts, you hit the letters of Paul. You might think they are ordered by when he wrote them. They aren't. They aren't even ordered by the importance of the city he was writing to.

Basically, they are ordered by length.

It sounds crazy, but it's true. Romans is the longest letter Paul wrote, so it goes first. Then 1 Corinthians, then 2 Corinthians, and so on, all the way down to Philemon, which is just a tiny little note. It’s like a librarian decided to organize a shelf by the size of the books rather than the Dewey Decimal System.

- Romans: The heavyweight champion of theology.

- The "Corinthians": Dealing with a messy, chaotic church.

- Galatians through Colossians: Shorter letters to specific regions.

- The "T-Letters": 1 & 2 Thessalonians.

- The Pastoral Epistles: 1 & 2 Timothy and Titus (written to individuals, not churches).

- Philemon: The shortest.

After Paul, you get the "General Epistles" like Hebrews, James, and Peter. These are generally grouped because they weren't written to one specific church but to the "general" Christian population.

👉 See also: Finding a Religious Chocolate Advent Calendar That Actually Focuses on Jesus

Why does the order even matter?

Does it change the meaning if you read it out of order? Not necessarily. But it does change your perspective. If you only read the New Testament Bible order as it is printed, you might miss the frantic, "boots-on-the-ground" energy of the early movement.

When you read Galatians knowing it was written while the church was in an absolute identity crisis, it hits different. When you realize that 1 Thessalonians was written to people who were genuinely confused about why their friends were dying before Jesus came back, the text stops being "ancient scripture" and starts being a real conversation.

The outliers: Hebrews and Revelation

Hebrews is a bit of a mystery. For a long time, people thought Paul wrote it, which is why it sits right after Philemon. Most scholars today are like, "Yeah, probably not Paul." But the order stuck. And then there's Revelation. It’s at the end because it’s the end. It deals with the eschaton—the final things. It’s the only book that really fits its physical location in the binding of the book.

How to actually read the New Testament for better context

If you want to move beyond just flipping pages, try these approaches. They help break the "length-based" monotony of the standard New Testament Bible order.

- The Luke-Acts Connection: Read Luke and then immediately read Acts. They are written by the same guy (Luke the physician) and are meant to be one continuous story. Reading them back-to-back is like watching a movie and its sequel in one sitting.

- The Chronological Paul: Start with 1 Thessalonians, then Galatians, then 1 & 2 Corinthians and Romans. It lets you see how Paul’s theology matured as he dealt with more complex problems.

- The Markan Start: Start with Mark. It’s fast. It’s raw. It gives you the "action movie" version of Jesus before you get into the dense, legalistic debates found in Matthew or the high-level philosophy of John.

Breaking down the timeline (The "Real" Order)

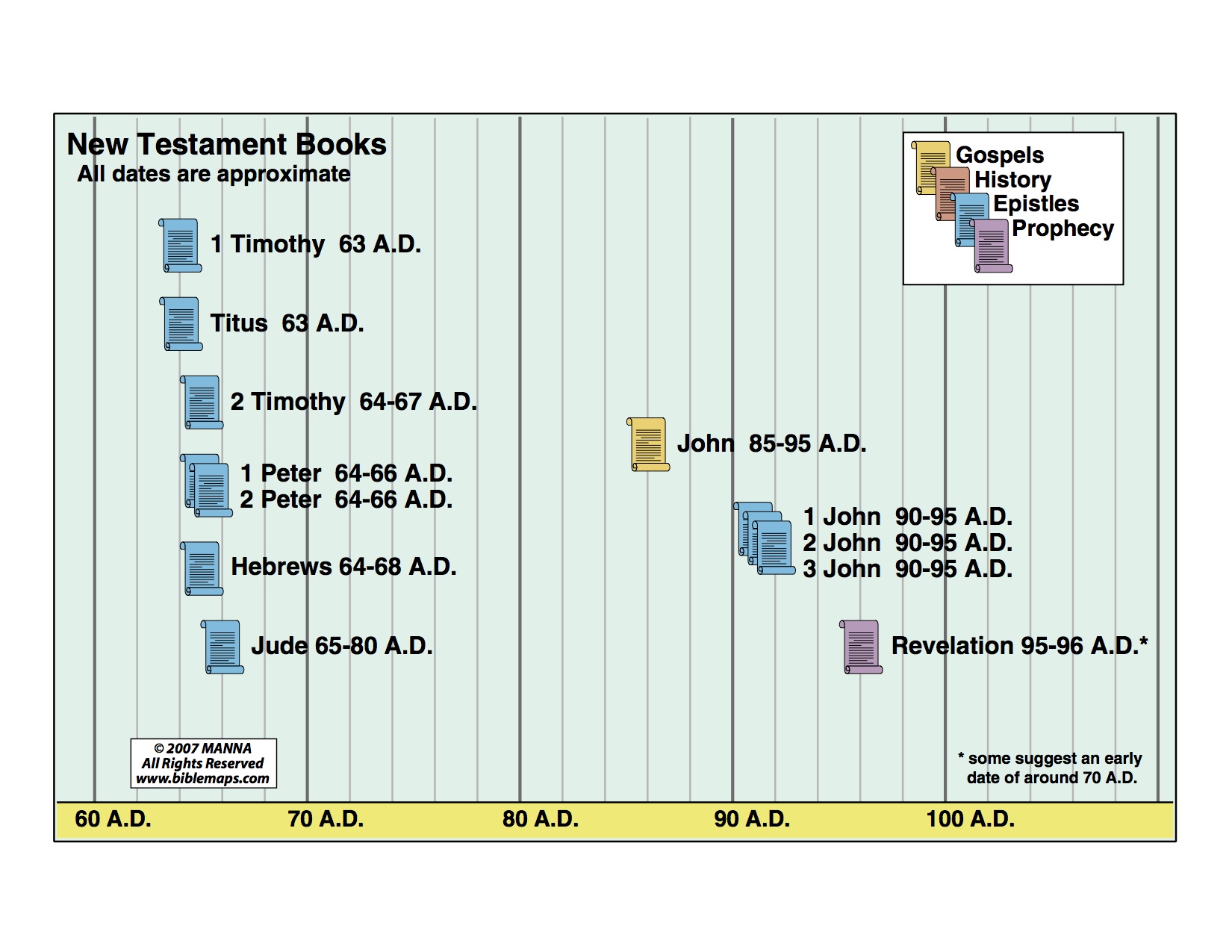

Since we know the New Testament Bible order we see today is more about categorization, what does the actual timeline look like? While dates are debated, the consensus usually falls somewhere in these windows:

- 50–60 AD: The early letters of Paul (1 Thessalonians, Galatians, Romans).

- 60–70 AD: The Gospel of Mark and the later Pauline letters.

- 70–85 AD: Matthew and Luke-Acts. By this point, the Temple in Jerusalem had been destroyed, which heavily influences the tone of these books.

- 90–100 AD: The Gospel of John, the letters of John, and Revelation.

It's a bit of a mind-trip to realize that for the first 20 years of the church, there were no "Gospels" to read. People relied on oral tradition and these circulating letters.

Actionable Next Steps

If you’re looking to deepen your understanding of how the New Testament came together, don't just take the table of contents at face value.

- Get a Chronological Study Bible. These are formatted to put the text in the order it was likely written or when the events occurred. It’s a total game-changer for seeing how ideas developed.

- Compare the "Big Three" Synoptics. Open Matthew, Mark, and Luke to the same story (like the feeding of the 5,000). Look at what Matthew adds and what Mark leaves out. You’ll start to see the "editor’s hand" in the New Testament Bible order.

- Read the "Intro" to each book. Most Bibles have a one-page summary before the book starts. Check the "Date Written" section. If you see a book written in 90 AD followed by one written in 55 AD, ask yourself why they are ordered that way. Usually, it's just because the first one was longer!

The Bible isn't just a book; it's a library. And like any library, the way the books are shelved tells you a lot about the people who organized it. Understanding the New Testament Bible order helps you realize that the early church wasn't just preserving a story—they were trying to build a cohesive narrative for a new movement.