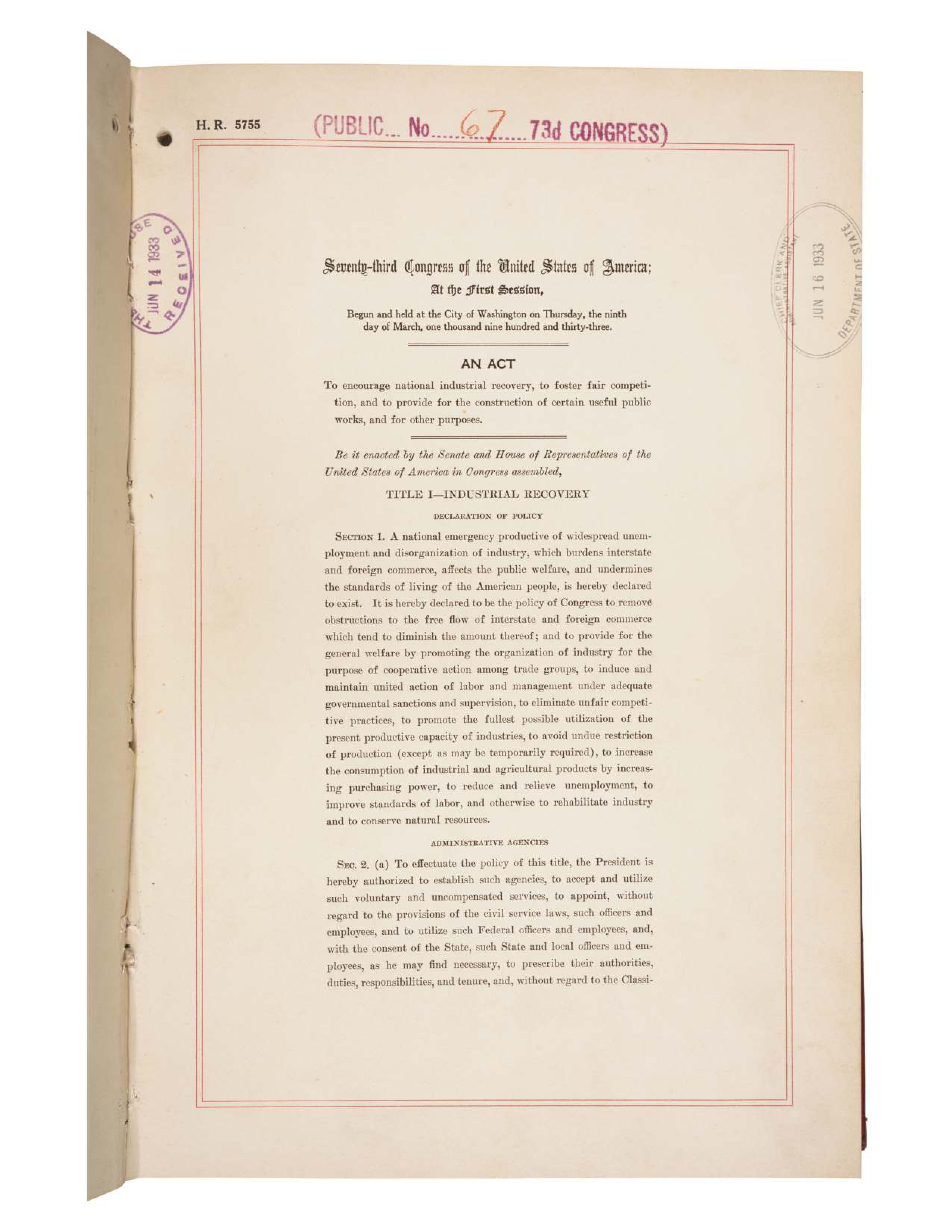

The Great Depression wasn't just a "bad economy." It was a total, terrifying collapse of the American way of life. By 1933, 13 million people were out of work. Banks were locking their doors. People were literally starving in the streets of the wealthiest nation on earth. Franklin D. Roosevelt stepped into this chaos and decided the government needed to stop playing referee and start playing quarterback. That's how we got the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933. It was the crown jewel of the New Deal, or at least it was supposed to be.

Honestly, it was a massive, messy experiment. FDR wanted to stop the "cutthroat competition" that was driving prices into the dirt and forcing companies to slash wages just to survive. The idea was simple: if businesses stopped fighting each other and started cooperating on prices and wages, everyone would win. Workers would get more money, businesses would stay afloat, and the economy would stabilize. But, as you've probably guessed, telling every business in America how to run their shop didn't go over perfectly.

What the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 Actually Did

The law was basically split into two halves. Title I was the part that dealt with industrial recovery. It created the National Recovery Administration, or the NRA. Not the gun guys—this was the "Blue Eagle" NRA. If you were a business owner back then, you wanted that Blue Eagle sticker in your window. It told customers "We do our part." To get it, you had to follow "codes of fair competition."

These codes weren't suggestions. They were law.

They set minimum wages, maximum hours, and even dictated how much you could charge for a haircut or a ton of coal. It was a wild departure from the "laissez-faire" capitalism that had ruled the US for decades. Suddenly, the federal government was in the boardroom. It was bold. It was also, according to some critics at the time, kinda sounding like the stuff happening in Italy or Germany. That's a heavy charge, but people were desperate.

The second half, Title II, created the Public Works Administration (PWA). This was the construction side of things. It poured $3.3 billion—a staggering amount of money in 1933—into big projects. We're talking bridges, dams, schools, and hospitals. If you’ve ever driven across the Triborough Bridge in New York or looked at the Hoover Dam, you’re looking at the legacy of the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933. It put people to work. Real work.

The Blue Eagle and the Power of Social Pressure

Hugh S. Johnson was the guy Roosevelt picked to run the NRA. He was a retired general with a loud mouth and a lot of energy. He knew he couldn't just sue every bakery in America that didn't follow the rules, so he used branding.

He created the Blue Eagle logo.

"May God have mercy on the man or group of men who attempt to trifle with this bird," Johnson famously said. It was intense. If a shop didn't display the eagle, the public was encouraged to boycott them. It worked for a while. Millions of people marched in parades for the NRA. But behind the scenes, the codes were becoming a nightmare. There were eventually over 500 different codes. One code for the "corrugated and solid fiber shipping container industry." Another for the "shoulder pad manufacturing industry." It was bureaucratic bloat on a level the country had never seen.

Why Section 7(a) Was a Total Game Changer

If you care about labor rights, the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 is basically your Genesis. Section 7(a) was a tiny part of the law that had a massive impact. It guaranteed workers the right to organize and bargain collectively through representatives of their own choosing.

Before this, joining a union could get you fired, blacklisted, or beaten up by "company police." Now, the law said you had a right to be there.

Union membership exploded. The United Mine Workers, led by John L. Lewis, sent organizers into the coal fields shouting, "The President wants you to join the union!" It wasn't strictly true—FDR was a bit more cautious than that—but it worked. This section laid the groundwork for the middle class we recognize today. It changed the power dynamic in the American workplace forever, even if the NRA itself didn't last.

The Famous Case of the "Sick Chickens"

Every big government program eventually hits a wall, and for the NRA, that wall was the Supreme Court. The case was A.L.A. Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States. It’s often called the "Sick Chicken Case."

The Schechter brothers ran a wholesale poultry business in Brooklyn. They were accused of violating the Live Poultry Code. Among other things, they were charged with selling an "unfit" chicken and letting customers pick their own chickens from a coop, which was against the rules (you were supposed to just reach in and take whatever came out).

The case went all the way to the top. In 1935, the Supreme Court dropped a hammer on the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933. They ruled it was unconstitutional.

The justices argued that the federal government didn't have the power to regulate "intrastate" commerce (business happening within one state). They also said Congress had given the President too much power to make laws through these codes. Just like that, the Blue Eagle was dead. Roosevelt was furious. He called the decision a "horse-and-buggy" interpretation of the Constitution.

Was it a Failure or a Success?

Economists still argue about this. Some say the NRA actually slowed down recovery by keeping prices artificially high and making it harder for small businesses to compete. They argue that the "codes" were basically government-sanctioned monopolies. Others point out that it stopped the downward spiral of wages and gave people hope when they had absolutely none.

It's complicated.

The PWA (Title II) was objectively a huge success in terms of infrastructure. It built the foundation of modern America. And while the NRA part was struck down, the ideas didn't go away. The labor protections in Section 7(a) were brought back and strengthened in the Wagner Act of 1935. The minimum wage and maximum hours ideas eventually became the Fair Labor Standards Act.

Basically, the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 failed as a law but succeeded as a blueprint. It changed the relationship between the American citizen and the federal government. It proved that in a crisis, the government could—and would—intervene in the economy.

Actionable Insights for Today

History isn't just a list of dates. If you’re looking at how the NIRA impacts us now, consider these points:

👉 See also: EZ Pack Holdings LLC: What Really Happened with the Trash Truck Titan

Understand the Legal Precedent

The "Sick Chicken" case is still cited in law schools today. It sets the boundary for how much power Congress can hand over to the Executive branch. When you hear people arguing about "administrative state" or "regulatory overreach" in the news today, they are essentially having the same argument the Schechter brothers had in 1935.

Labor Power is Rooted Here

If you are involved in collective bargaining or labor relations, you’re working in the shadow of Section 7(a). It was the first time the US government took a pro-union stance on a national scale. Recognizing that historical shift helps explain why labor laws are structured the way they are today.

Infrastructure as Stimulus

The PWA side of the NIRA proved that government spending on physical infrastructure is one of the most effective ways to create jobs and long-term value. Whenever a new "Infrastructure Bill" comes through Congress, it's using the NIRA's playbook.

The Danger of Centralized Planning

The NIRA's collapse serves as a warning about trying to micromanage every detail of an economy. Creating 500+ codes for every tiny industry was impossible to enforce and created massive resentment. It shows that while government intervention can save a sinking ship, too much of it can capsize the boat.

To really understand the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933, you have to look at the Library of Congress archives or read the original 1933 text. You'll see the desperation of the era written between the lines. It was a time of "try anything" politics. Some of it worked, some of it was a disaster, but the America that came out the other side was fundamentally different than the one that went in.