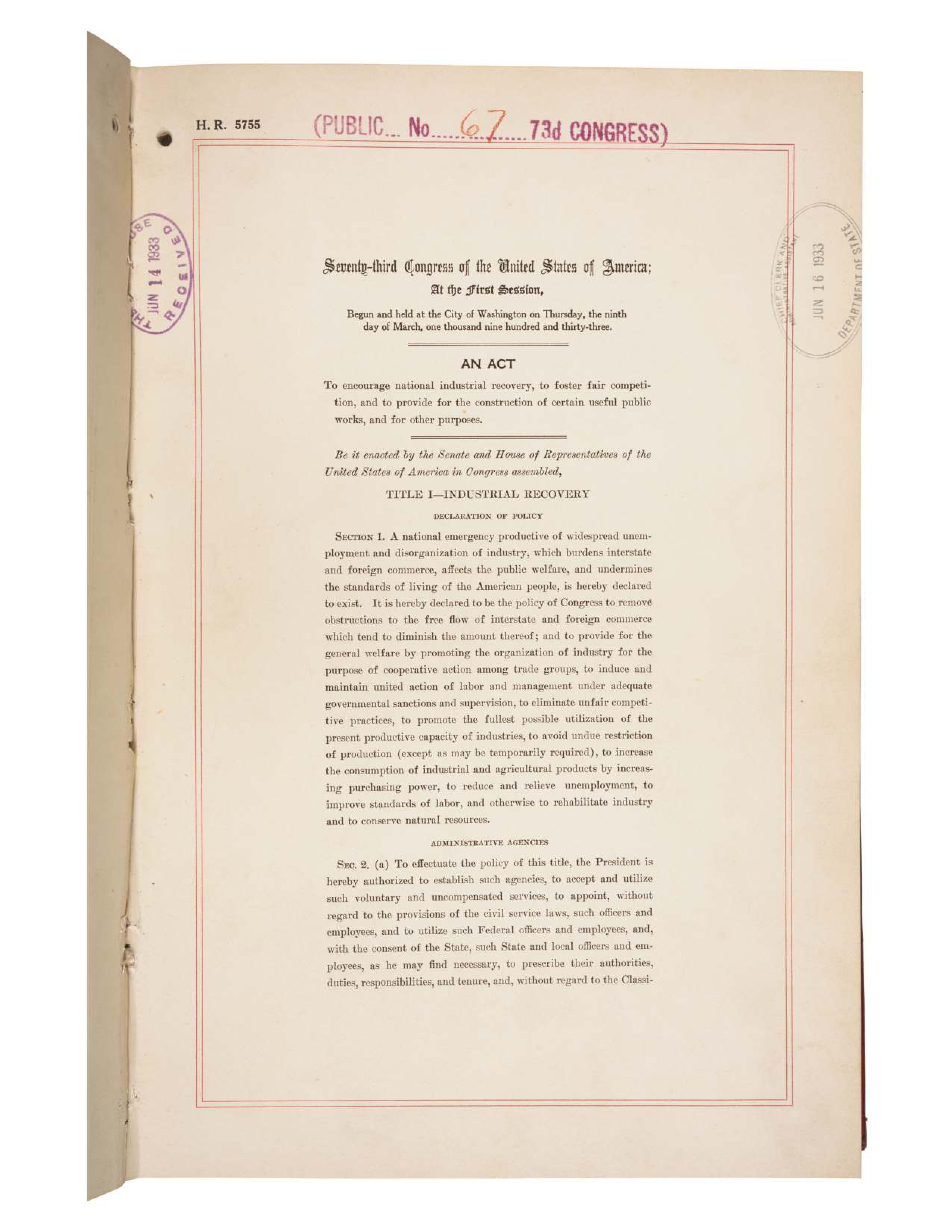

Franklin D. Roosevelt had been in office for roughly one hundred days when he signed the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933. The country was a mess. One out of every four people couldn't find a job, and the ones who had work were watching their wages slide into the basement. People were desperate. Honestly, the NIRA was basically a "hail mary" pass designed to stop the bleeding of the Great Depression by fundamentally changing how American business functioned. It wasn't just a law; it was a total overhaul of the relationship between the government, the boss, and the worker.

You’ve probably seen the blue eagle posters in old history books. That was the symbol of the NRA—the National Recovery Administration—which the act created. Businesses that played ball got to display that eagle. If you didn't? Well, you were basically branded as a traitor to the recovery. It was intense.

The Wild Ambition of the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933

The core idea was simple but radical: stop "cutthroat competition." In 1933, businesses were undercutting each other so hard on prices that they were going broke, which led to layoffs, which led to less spending, which led to more price cuts. A death spiral. FDR and his advisors, like Raymond Moley and Rexford Tugman, thought they could fix this by letting industries write "codes of fair competition."

These codes were basically rules for how to run a business. They set minimum wages. They limited how many hours a person could work in a week so that the remaining work could be spread around to more people. They even set floor prices for goods.

It sounds like a dream for workers, right? In many ways, it was. Section 7(a) of the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 was a bombshell. It gave workers the right to organize and bargain collectively. This was the first time the federal government really stepped up and said, "Yes, unions are legal and protected." Before this, trying to start a union often ended with getting your head cracked by a company goon or getting fired on the spot. Suddenly, the law was on the worker's side.

But here is where it gets messy. Because the government allowed businesses to collude on prices (something that usually gets you thrown in jail for antitrust violations), the big players in each industry basically wrote the rules to screw over the small guys. If you were a small dry cleaner in Brooklyn, you suddenly had to follow the same price and wage rules as a massive industrial chain. It didn't always work out.

📖 Related: Neiman Marcus in Manhattan New York: What Really Happened to the Hudson Yards Giant

The Blue Eagle and the Pressure to Conform

The NRA chief was a guy named Hugh S. Johnson. He was a retired general with a massive personality and a drinking habit to match. He ran the NRA like a military campaign. He staged parades. He gave fiery speeches. He wanted every American consumer to only buy from businesses that displayed that Blue Eagle.

"We Do Our Part." That was the slogan.

It was essentially a government-sanctioned boycott. If a shop didn't have the sticker, people assumed they were exploiting workers or selling "hot goods." This created a massive amount of social pressure. Imagine if today the government told you that you were "un-American" for buying a latte from a shop that didn't follow a specific federal pricing index. That’s what it felt like.

Why the Supreme Court Killed It

The National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 didn't last long. It was signed in June 1933, and by May 1935, it was dead. The end came because of chickens. Seriously.

The case was A.L.A. Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States. The Schechter brothers ran a wholesale poultry business in Brooklyn. They were accused of violating the "Live Poultry Code"—specifically, they were accused of selling "unfit" chickens and ignoring the wage and hour rules. They fought it all the way to the Supreme Court.

👉 See also: Rough Tax Return Calculator: How to Estimate Your Refund Without Losing Your Mind

The Court was unanimous. They ruled that the NIRA was unconstitutional for two big reasons. First, the government was delegating too much legislative power to the executive branch and private industry groups. You can't just let a bunch of business owners write laws. Second, the Court said the federal government didn't have the power to regulate "intrastate" commerce—business that happens entirely within one state—under the Commerce Clause.

FDR was furious. He called it a "horse-and-buggy" interpretation of the Constitution. But the NIRA was gone. Just like that.

The Long-Term Impact on Business and Labor

Even though it failed as a law, the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 changed everything. It was like a rough draft for the modern American economy. When it died, the government didn't just give up. They took the pieces that worked and made them separate laws.

The labor protections from Section 7(a) eventually became the Wagner Act (National Labor Relations Act) of 1935. The wage and hour ideas eventually turned into the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, which gave us the 40-hour workweek and the minimum wage we still argue about today.

It also changed the way we think about the "safety net." Before 1933, the idea that the federal government was responsible for your paycheck or your working conditions was pretty foreign. After the NIRA, it became the expectation.

✨ Don't miss: Replacement Walk In Cooler Doors: What Most People Get Wrong About Efficiency

What Most People Get Wrong About 1933

A lot of people think the NIRA saved the economy. Honestly? Most economists today think it might have actually slowed down the recovery. By keeping prices artificially high and allowing big companies to act like monopolies, it made it harder for the economy to naturally adjust. It created a lot of bureaucracy and "red tape" before that was even a common phrase.

However, you can't ignore the psychological boost it gave the country. For a few years, it felt like someone was actually in charge and doing something.

Real-World Takeaways for Business Leaders

If you look at the history of the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933, there are some pretty clear lessons for how we handle economic crises today.

- Top-down control is hard. Trying to micromanage every industry from a central office in D.C. resulted in "codes" that were thousands of pages long and impossible to enforce fairly.

- Labor rights are sticky. Once you give workers the right to organize, you can't easily take it back. The surge in union membership during the NIRA years changed the power balance of the 20th century.

- Public sentiment is a tool. The Blue Eagle campaign showed that you don't always need a law to change behavior if you have a strong enough brand and enough social pressure.

Practical Steps for Understanding Economic Policy

History repeats itself, especially when it comes to government intervention in the markets. To truly understand how acts like the NIRA influence today’s landscape, consider these actions:

- Audit your industry's "hidden" codes. While we don't have an NRA today, look at how industry trade groups and lobbyists set standards that function similarly to the 1933 codes, often favoring established players over startups.

- Study the Wagner Act. Since this was the direct "child" of the NIRA, understanding its current state will give you a better handle on modern labor disputes and unionization efforts at companies like Amazon or Starbucks.

- Trace the Commerce Clause. Keep an eye on Supreme Court cases involving the Commerce Clause. The same legal arguments used to kill the NIRA are still used today to challenge federal regulations on everything from healthcare to the environment.

- Evaluate "Social License." Look at modern ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) movements. In many ways, they are the digital version of the Blue Eagle—a way for companies to show they are "doing their part" to avoid consumer boycotts, regardless of whether a specific law requires it.

The National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 was a flawed, messy, and ultimately unconstitutional experiment. But it was also the moment America decided that the "free market" shouldn't be a free-for-all at the expense of the human being. Whether you think it was a bold rescue or a bureaucratic disaster, we are still living in the world it built.