The Great Depression wasn't just a "bad economy." It was a collapse of the very idea of American industry. By the time Franklin D. Roosevelt took office in March 1933, the country was effectively bleeding out. Banks were closed. Factories were silent. People were desperate. To stop the bleeding, FDR threw a massive, experimental bandage over the whole thing called the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933.

It was a wild gamble.

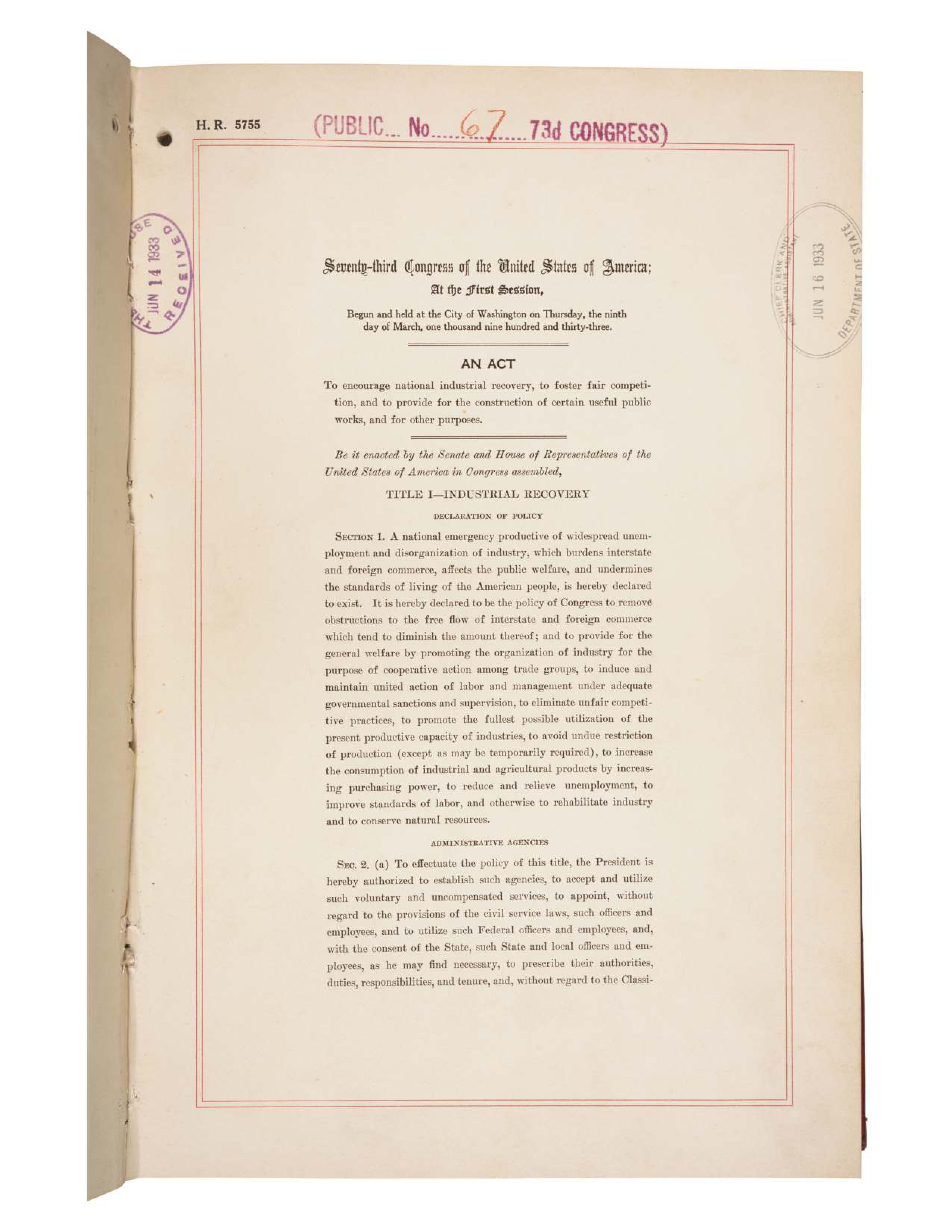

Honestly, the NIRA was probably the most ambitious—and controversial—piece of legislation ever passed in Washington. It didn't just try to tweak interest rates or hand out a few checks. It tried to reorganize the entire American economy from the top down.

Think about that.

The government basically told every major industry, from coal mining to dry cleaning, that they had to sit in a room and agree on "codes of fair competition." They wanted to stop the "race to the bottom" where companies kept cutting wages just to survive. If you’ve ever wondered why we have a 40-hour work week or why you have a legal right to join a union, you can trace a lot of those DNA strands back to this one messy, 1933 law.

What the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 actually did

The law was split into two main chunks, or "Titles." Title I was the part everyone talked about—the National Recovery Administration (NRA). No, not the gun guys. This NRA was led by a colorful, cigar-chomping former general named Hugh S. Johnson. He was a polarizing figure, to say the least.

The goal was simple: stop the cutthroat price-cutting. Under the NRA, businesses in the same sector drafted "codes." These codes set minimum wages, maximum hours, and even prices. If a business followed the rules, they got to display a "Blue Eagle" poster in their window with the slogan "We Do Our Part."

People took this seriously.

✨ Don't miss: Why Every Tornado Warning MN Now Live Alert Demands Your Immediate Attention

You’ve got to imagine the social pressure. If a grocery store didn't have that Blue Eagle in the window, neighbors would often boycott them. It was a sort of patriotic peer pressure meant to keep the economy from eating itself.

Then there was Title II. This created the Public Works Administration (PWA). While the NRA was busy trying to manage prices, the PWA was out there building things. We're talking massive infrastructure—the stuff we still use. The Hoover Dam? The Triborough Bridge? The Overseas Highway to Key West? All of that happened because of the funding mechanisms tucked inside the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933.

The Section 7(a) Bombshell

If you ask a labor historian about this law, they won’t talk about the Blue Eagle. They’ll talk about Section 7(a).

This tiny section was a revolution in print. It stated, for the first time in federal law, that workers had the right to organize and bargain collectively through representatives of their own choosing. Before this, if you tried to start a union, your boss could basically fire you, blackball you, or call in private security to break your legs.

Section 7(a) changed the vibe.

Suddenly, workers felt like the President wanted them to join a union. John L. Lewis, the legendary leader of the United Mine Workers, famously sent organizers into the coal fields shouting, "The President wants you to join the union!" It wasn't technically true—FDR was a bit more cautious than that—but the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 gave them the legal cover they needed to try.

Why it didn't actually work (and why that's okay)

Here is the truth: the NIRA was a bit of a disaster in practice.

🔗 Read more: Brian Walshe Trial Date: What Really Happened with the Verdict

It was too big. Too fast. Too bureaucratic.

Imagine trying to write specific rules for 500 different industries in just a few months. You had codes for the "Legitimate Full-Length Dramatic and Musical Theatrical Industry" and codes for the "Dog Food Industry." It became a joke. Big companies often hijacked the code-writing process to crush their smaller competitors. If you were a small mom-and-pop shop, you couldn't always afford the higher wages the big guys agreed to.

Prices started to rise faster than wages.

By 1934, the honeymoon was over. People started calling the NRA "National Run Around" or "Nuts Running America." The General in charge, Hugh Johnson, was eventually pushed out as the administration became a tangled mess of red tape and lawsuits.

Then came the "Sick Chicken Case."

In 1935, a small poultry company in Brooklyn—A.L.A. Schechter Poultry Corp.—was accused of violating the Live Poultry Code. They were selling "unfit" chickens and ignoring wage/hour rules. The case went all the way to the Supreme Court. In Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States, the Court basically nuked the entire NRA. They ruled that the government couldn't delegate that much power to the President and that the feds didn't have the right to regulate local businesses that didn't do interstate commerce.

The National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 was dead.

💡 You might also like: How Old is CHRR? What People Get Wrong About the Ohio State Research Giant

The ghost of the NIRA

Even though the law was struck down, it didn't really "die." It just morphed.

FDR and his allies realized they couldn't do everything at once, so they broke the NIRA into pieces. The labor protections from Section 7(a) became the National Labor Relations Act (Wagner Act) of 1935. The wage and hour standards eventually became the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938.

We kept the parts that worked and ditched the parts that didn't.

Lessons for the 2020s

You see a lot of echoes of the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 in today’s debates about the "Green New Deal" or industrial policy. Whenever someone says the government should help guide certain industries—like electric vehicles or microchips—they are using the logic of the NIRA.

The big takeaway? Regulation is hard.

When you try to plan an entire economy, you get "unintended consequences." But when you do nothing, you get the Great Depression. The NIRA was a middle ground. It failed as a law, but it succeeded as a psychological shock to the system. It gave people hope when they had none.

If you’re researching this period, don’t just look at the legal text. Look at the posters. Look at the photos of "NRA parades" where thousands of people marched in the streets just because they felt like someone was finally trying something.

Actionable insights from the 1933 experience

- For business owners: The NIRA proves that "voluntary" industry standards usually favor the biggest players. If you see a trade association pushing for new regulations today, check if those rules might accidentally (or intentionally) squeeze out smaller startups.

- For workers: Understanding the NIRA helps you realize that labor rights aren't "natural." They were fought for in the 1930s through massive strikes and messy legislation. Section 7(a) is the grandfather of your right to discuss pay with your coworkers today.

- For policy nerds: The "Sick Chicken" case is a masterclass in constitutional limits. It’s a reminder that even in a national emergency, the U.S. government has to follow the rules of the road regarding "interstate commerce."

- Further Reading: If you want the real, gritty details, check out The Coming of the New Deal by Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. It’s an old book, but it captures the chaos of the NRA offices better than anything written recently. You can also dig through the National Archives to see the original "Blue Eagle" posters and the letters from ordinary citizens complaining about their local "code violators."

The National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 wasn't a perfect solution. Far from it. But it was a bold attempt to answer a question we are still asking: how much should the government interfere to keep the economy fair for everyone? We still haven't quite figured that one out.

Study the history of the NRA's Public Works Administration projects in your local area; many parks, schools, and bridges built with those 1933 funds are still standing and serve as a physical record of the Act's enduring legacy. Check the cornerstones of older public buildings—you might just find a brass plaque from that era.