If you’ve ever walked through the winding, salt-crusted alleys of Gamaliya in Old Cairo, you’ve felt it. That heavy, humid sense of history pressing in from the limestone walls. It’s exactly the atmosphere Naguib Mahfouz bottled up in his masterpiece. Honestly, the Naguib Mahfouz Cairo Trilogy isn't just a set of books. It’s a time machine. It’s a family therapy session gone wrong. It’s a brutal, honest look at how a country breaks apart and puts itself back together through the eyes of one chaotic household.

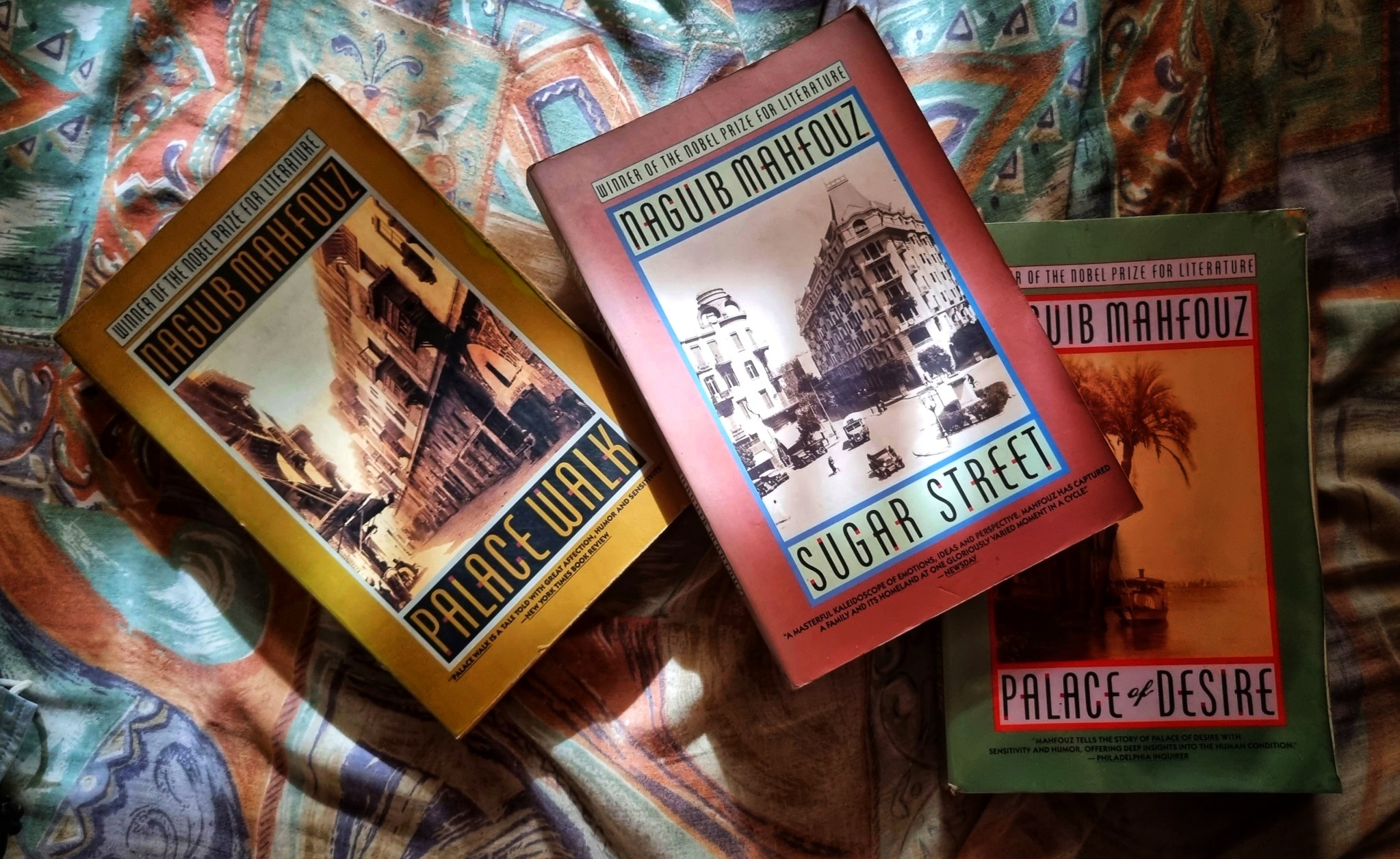

Most people hear "classic literature" and think of dry, dusty pages and homework. That's a mistake. This trilogy—Palace Walk, Palace of Desire, and Sugar Street—is essentially the original prestige TV drama. You’ve got a tyrannical father living a double life, children struggling with repressed sexuality and political radicalism, and a mother who represents the silent heart of a vanishing world.

Mahfouz didn't just write these stories; he lived them. He was born in 1911, right in the thick of the British occupation, and he watched the 1919 Revolution from his window as a kid. That raw, firsthand energy is why the Naguib Mahfouz Cairo Trilogy feels so visceral. It isn't just about "history." It's about how history ruins your dinner and dictates who you’re allowed to love.

The Tyrant of Palace Walk

Let’s talk about Al-Sayyid Ahmad Abd al-Jawad. He is, without a doubt, one of the most complex "villains" in literary history, though Mahfouz would probably just call him a man of his time.

During the day and into the night, he’s a carouser. He drinks, he dances, he spends time with beautiful performers, and he’s the life of the party among his elite Cairo social circle. But the second he steps across his own threshold? Total silence. His wife, Amina, and their children live in a state of perpetual "yes, sir." He rules with an iron fist.

It's a bizarre duality.

The first book, Palace Walk (Bayn al-Qasrayn), focuses on this suffocating domesticity. Amina isn’t even allowed to leave the house. Ever. When she finally dares to step outside to visit a nearby mosque while her husband is away, it triggers a family catastrophe. It sounds small to a modern reader, but in the context of 1917 Cairo, it’s an earthquake.

Mahfouz uses this family as a microcosm for Egypt itself. Just as the Egyptian people were chafing under British rule, the family was chafing under the Al-Jawad patriarch. The tension is palpable. You can almost smell the incense and the jasmine. Then the 1919 Revolution breaks out, and the political world crashes into the private world. Fahmy, the idealistic son, becomes the heartbeat of the resistance. His fate—which I won’t spoil, though the book has been out since the 50s—is the moment the trilogy shifts from a family drama into a national epic.

What People Get Wrong About Mahfouz

There is a common misconception that Mahfouz was just a "realist" who took notes on what he saw. People think he was just a guy with a clipboard.

✨ Don't miss: Weather Forecast Calumet MI: What Most People Get Wrong About Keweenaw Winters

That’s wrong.

He was a philosopher by training. He studied at Cairo University and was obsessed with the tension between science and religion. You see this play out in the second and third books, Palace of Desire (Qasr al-Shawq) and Sugar Street (al-Sukkariyya).

The character Kamal is basically Mahfouz’s surrogate. Kamal grows up, loses his faith, falls into unrequited love, and spends his time arguing about Darwin and Nietzsche while his brothers get involved in the Muslim Brotherhood or the Communist party.

It’s messy.

Life is messy.

The Naguib Mahfouz Cairo Trilogy works because it doesn't offer easy answers. It shows that even when the British leave, or even when the old patriarch dies, the problems don't just vanish. They just change shape. The "Old Cairo" of the first book, with its rigid codes of honor, slowly dissolves into the modern, cynical, politically fractured Cairo of the 1940s.

The Language of the Streets

One thing that’s hard to capture in translation is the "vibe" of the Arabic. Mahfouz was a master of using Modern Standard Arabic to describe things that were intensely local and colloquial.

He made the street names famous.

🔗 Read more: January 14, 2026: Why This Wednesday Actually Matters More Than You Think

- Bayn al-Qasrayn: Between the two palaces.

- Qasr al-Shawq: Palace of desire.

- Al-Sukkariyya: Sugar street.

These aren't just poetic titles; they are actual locations in the Gamaliya district. If you go there today, you can find the shops and the balconies he described. Critics like Edward Said have pointed out that Mahfouz did for Cairo what Dickens did for London or Balzac did for Paris. He mapped the soul of the city.

But unlike Dickens, Mahfouz has this specific Middle Eastern fatalism. There’s a sense that time is a circle. By the time we get to the third generation of the family in Sugar Street, we see the grandsons repeating the same mistakes their grandfather made, just under different political banners. One grandson is a devout Islamist; the other is a staunch Marxist. They both end up in the same prison cell.

The irony is thick enough to cut with a knife.

Why You Should Care in 2026

You might be wondering why a series of books written in the 1950s about the 1920s matters now.

Because we are still living in the world Mahfouz described.

The clash between tradition and modernity? Still happening. The struggle of women to claim space in a patriarchal society? Still the headline news. The feeling that your government doesn't represent you? That’s universal.

The Naguib Mahfouz Cairo Trilogy is a masterclass in E-E-A-T (Experience, Expertise, Authoritativeness, and Trustworthiness) before that was even a Google acronym. Mahfouz had the lived experience of the transition from monarchy to republic. He had the expertise of a civil servant who saw the inner workings of the Egyptian bureaucracy. He wrote with an authority that eventually earned him the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1988—the first Arabic-language writer to ever get it.

When you read these books, you aren't just "consuming content." You’re absorbing a century of cultural evolution.

💡 You might also like: Black Red Wing Shoes: Why the Heritage Flex Still Wins in 2026

The Evolution of the Family Dynamic

In the first book, the family is a monolith. In the second, it’s a fragmenting mirror. By the third, it’s a pile of shards.

Amina, the mother, is perhaps the most tragic and beautiful figure. She begins as a woman who isn't allowed to see the street, but by the end, she is the only thing holding the memory of the family together. Her resilience is quiet. It isn't the loud, shouting resilience of the politicians. It’s the resilience of someone who keeps making bread while the world burns.

Mahfouz shows us that change is inevitable, but it’s rarely a straight line. It’s a zig-zag.

The grandkids in Sugar Street think they are so much more "advanced" than their grandfather, Al-Sayyid Ahmad. But in their own ways, they are just as dogmatic. They’ve replaced his religious/patriarchal dogma with political dogma. Mahfouz sort of stands back and watches this with a weary, knowing smile. He’s seen it all before.

Actionable Steps for Navigating the Trilogy

If you’re ready to tackle this mountain of literature, don't just dive in blindly. You'll get lost in the names.

- Get the Everyman’s Library edition. The translation by William Maynard Hutchins and others is generally considered the gold standard for English speakers. It flows naturally and captures the grit.

- Keep a family tree. Seriously. By the time you get to the third book, the number of grandchildren and their varying political affiliations will make your head spin. Scribble a map on a bookmark.

- Read it for the gossip first. Forget the "literary importance" for a second. Read it for the drama. Read it for the scandalous affairs, the secret meetings, and the family blowouts. The "meaning" will find you eventually, but the story is what keeps you turning pages.

- Watch the old Egyptian films. If you can find them with subtitles, the 1960s film adaptations are iconic. They give a visual face to the characters that is hard to shake once you’ve seen it.

- Visit the Naguib Mahfouz Museum. If you ever find yourself in Cairo, go to the Al-Tekkeyya Al-Gulshany in the Gamaliya district. It’s a dedicated space that houses his personal belongings and medals. Seeing his small, round glasses and his simple desk makes the epic scale of the Trilogy feel much more human.

The Naguib Mahfouz Cairo Trilogy is a commitment. It’s over 1,300 pages of text. But it’s a commitment that pays off because it changes how you see the world. It teaches you that every person walking down a crowded street is carrying an entire world of history, secrets, and ghosts behind their eyes. That’s the magic of Mahfouz. He turned a few streets in Cairo into the center of the universe.

To truly understand the impact of his work, start with the first hundred pages of Palace Walk. Pay attention to the way the house feels like a character itself. Notice how the light hits the "mashrabiya" screens. Once you feel the atmosphere, the rest of the 1,200 pages will fly by. Focus on the relationship between Kamal and his father; it's the emotional core that explains the shift from old Egypt to the new world.