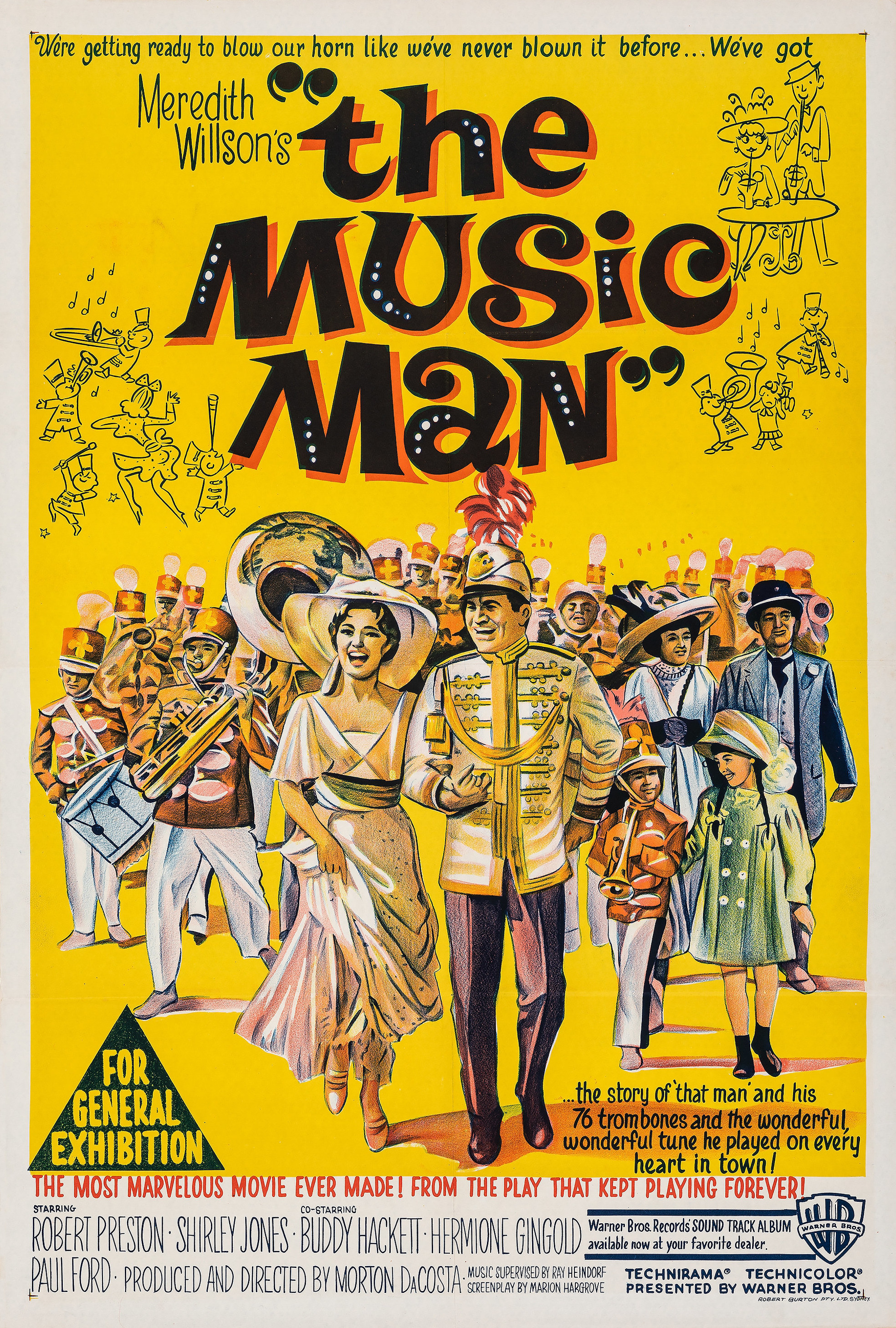

You know that feeling when a movie just clicks? It’s not just the nostalgia or the Technicolor glow. It’s the rhythm. When the music man movie 1962 hit theaters, it wasn't just another Broadway transfer. It was a lightning strike. Honestly, if you look at the landscape of movie musicals today, they often feel sterilized or over-edited. But in 1962, Morton DaCosta—who also directed the stage version—did something pretty ballsy. He kept it theatrical. He didn't try to make it "gritty" or "realistic." He leaned into the artifice, and that’s exactly why we’re still talking about Professor Harold Hill sixty-plus years later.

The Robert Preston Factor: Why Casting Almost Ruined Everything

Let’s be real for a second. Warner Bros. almost blew it.

Big time.

Jack Warner, the legendary and often stubborn head of the studio, didn't want Robert Preston. He wanted Frank Sinatra. Can you imagine? Ol' Blue Eyes as Harold Hill? It would have been a disaster. Sinatra had the pipes, sure, but he didn't have the "rhythm speech" down. He didn't have that frantic, fast-talking, Midwestern con-man energy that Preston had pioneered on Broadway since 1957.

Preston had played the role over 1,300 times before the cameras even started rolling. He knew the character in his bones. Thankfully, Meredith Willson, the creator of the show, dug his heels in. He basically told the studio that if Preston wasn't the lead, they weren't getting the movie. It’s one of those rare moments in Hollywood history where the right creative decision actually won out over the "safe" commercial one.

The Shirley Jones Contrast

Then you’ve got Shirley Jones. She was fresh off an Oscar win for Elmer Gantry, which is about as far from a wholesome librarian as you can get. She brought a certain gravity to Marian Paroo. While Preston is bouncing off the walls, Jones provides the soul. Plus, she was actually pregnant during filming! If you look closely at some of those wide shots in the "76 Trombones" reprise, they had to be really careful with the costuming and angles to hide her growing bump.

Why the Music Man Movie 1962 Beats the Stage Version

Purists might argue, but the film adds a layer of Americana that the stage simply can’t capture.

📖 Related: Ashley Johnson: The Last of Us Voice Actress Who Changed Everything

The scale is massive.

When you see that final parade, it’s not just ten actors in hats. It’s a wall of brass. The production design by Paul Groesse is a masterclass in stylized realism. River City, Iowa, looks like a postcard that’s come to life, but it has these sharp, satirical edges. It’s a critique of small-mindedness just as much as it is a celebration of community.

Technical Wizardry in "Rock Island"

Think about the opening number, "Rock Island." There’s no music. It’s just the cadence of a train. In the music man movie 1962, the editing by William H. Ziegler matches the syncopation of the dialogue perfectly. The actors are swaying in unison to simulate the motion of the train car, creating a percussive foundation out of thin air. It’s a technical nightmare to film because if one person misses a beat, the whole illusion shatters.

Modern directors would probably use CGI or shaky cam to fix it. In '62? They just rehearsed until their feet bled.

The Secret Ingredient: Meredith Willson’s Iowa

A lot of people think The Music Man is just a lighthearted romp. It’s actually quite personal. Meredith Willson based River City on his hometown of Mason City, Iowa. He spent years trying to get the script right, famously going through dozens of drafts and cutting over forty songs before the show ever hit Broadway.

That’s why the dialogue feels so authentic.

👉 See also: Archie Bunker's Place Season 1: Why the All in the Family Spin-off Was Weirder Than You Remember

- "You've got trouble, right here in River City!"

- "I’ll tell you what’s gonna happen..."

- "A chunk of fudge for a woman who never spelled 'libertine'!"

It's specific. It’s weird. It’s packed with 1912 slang that somehow feels universal. Willson wasn't just writing "songs"; he was writing a rhythmic language.

The Supporting Cast Nobody Remembers (But Should)

We have to talk about the Buffalo Bills. No, not the football team. The barbershop quartet. They were actual champion singers (the 1950 SPEBSQSA champions, to be precise). Their integration into the plot—where Harold Hill uses music to distract the school board from seeing his lack of credentials—is a genius bit of writing. Every time they start singing "Lida Rose" or "Sincere," the movie stops being a plot and starts being an experience.

And then there's Hermione Gingold as Eulalie Mackecknie Shinn. Her interpretation of "the Grecian Urn" is peak physical comedy. She represents the pomposity of the town, but she does it with such flair that you can't help but love her.

Addressing the "Stiff" Critique

Some modern critics say the music man movie 1962 is too long or too "stagey."

I disagree.

The length (151 minutes) is necessary. You need that time to feel the town’s resistance soften. If Harold Hill wins them over in ninety minutes, it feels like a cheap trick. When it takes two and a half hours, it feels like a conversion. You see the change in Winthrop (played by a very young Ron Howard). That kid’s lisp wasn't just a gimmick; it was a symbol of his social anxiety, and music was the cure.

✨ Don't miss: Anne Hathaway in The Dark Knight Rises: What Most People Get Wrong

Speaking of Ron Howard, he’s actually quite good here. It’s easy to forget he was a child star before he was an Oscar-winning director. His performance in "Gary, Indiana" is genuinely charming without being overly "theatre kid" annoying.

The Legacy of 76 Trombones

The finale is where everything comes together. It’s loud. It’s brassy. It’s arguably one of the best-edited sequences in musical cinema. The way the "Think System" actually manifests—not as perfect music, but as a community coming together to support their kids—is the real heart of the film.

Harold Hill is a liar. He’s a fraud. He doesn't know a note of music.

But as Marian says, he gave the town something they never had: a reason to look at each other. He gave them "the bells on the hill." That nuance—that a con man can accidentally do more good than the "upright" citizens—is what keeps the movie from being sugary sweet. It’s got a bit of a bite to it.

How to Experience it Today

If you’re going to revisit this classic, don’t watch it on a phone. Please. The 4K restoration that’s been floating around recently is stunning. The colors pop in a way that modern digital films just can't replicate. The "Shipoopi" sequence alone is a riot of color that deserves a big screen.

Actionable Ways to Appreciate the Film:

- Listen to the "Rock Island" track first. Put on some good headphones and just listen to the rhythm. Notice how the "sh-sh-sh" of the steam engine is replicated by the actors' voices.

- Watch the 2003 and 2022 versions for comparison. If you want to see why the 1962 version reigns supreme, watch Matthew Broderick or Hugh Jackman tackle the role. They’re great performers, but they lack Preston's specific, frantic "vocal percussion."

- Check out the Mason City connection. If you're ever in Iowa, visit "The Music Man Square." It’s a trip to see how much of the film’s "fiction" was actually pulled directly from Willson’s real-life memories.

The music man movie 1962 isn't just a relic. It’s a blueprint for how to adapt a stage play without losing its soul. It understands that sometimes, the most "realistic" way to tell a story is to let the characters burst into song.

To really get the most out of your next viewing, pay close attention to the background characters in the "Marian the Librarian" sequence. Every single person in that library has a choreographed arc. It’s a level of detail that you just don't see much anymore. Go back and watch it again with a focus on the choreography by Onna White—it’s arguably some of the most athletic and inventive work of the era.