Blake Edwards was on fire in the late fifties. He had already given the world Peter Gunn, a show that basically redefined "cool" for the television screen, but then he decided to pivot. He wanted something smoother. More elegant. That’s how we got the Mr. Lucky TV series, a show that feels like a stiff drink in a high-end lounge. It only lasted one season, from 1959 to 1960, but honestly? It left a fingerprint on the medium that’s still visible if you know where to look.

You’ve got John Vivyan playing the lead, a guy named Mr. Lucky. He’s a professional gambler. Not the gritty, desperate kind you see in modern Vegas movies, but a sophisticated operator with a tuxedo and a moral compass that points, mostly, in the right direction. He runs a high-stakes gambling yacht called the Fortuna. It’s anchored just outside the three-mile limit to keep things legal—or at least legal-ish.

The DNA of Cool

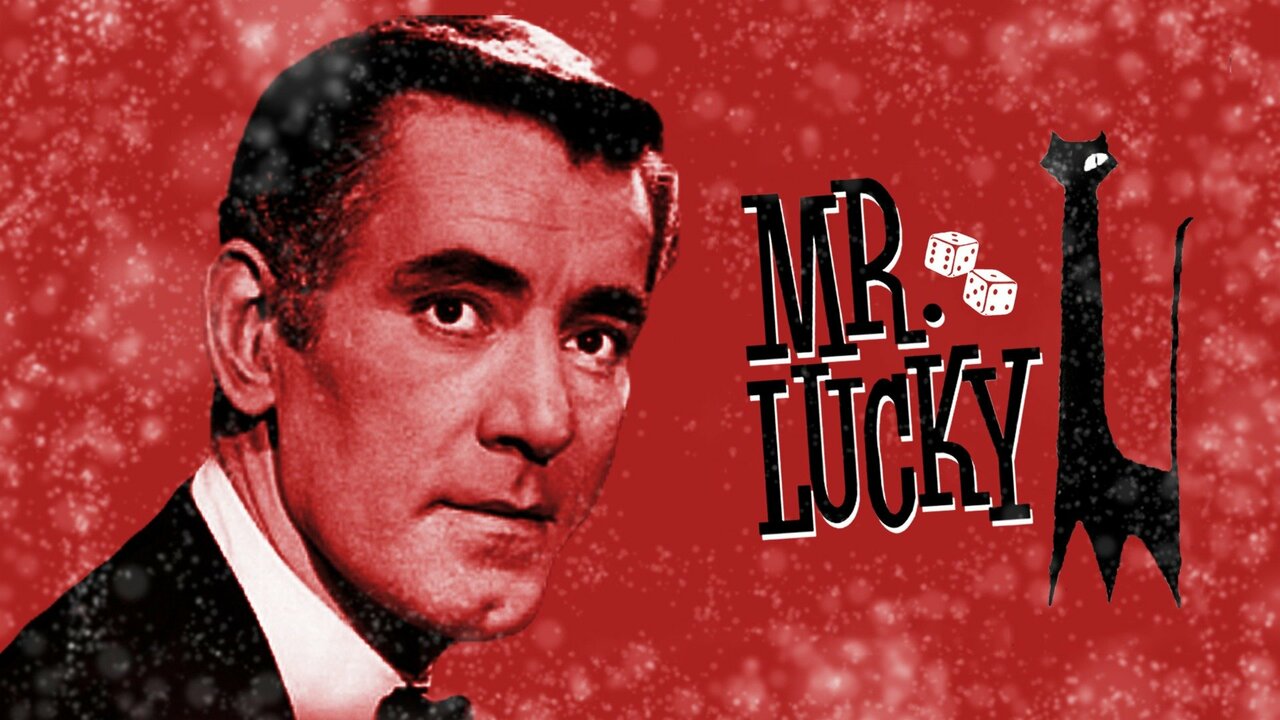

The show didn't just appear out of thin air. It was loosely—and I mean very loosely—based on the 1943 film Mr. Lucky starring Cary Grant. But where the movie was a wartime romantic drama, the TV show was a sleek, weekly adventure. It captured a specific post-war American aspiration. People wanted to be the guy who didn't sweat. They wanted to be the guy who could handle a crooked card shark in the morning and a beautiful woman in the evening without losing his cool.

Ross Martin played Andamo, Lucky’s right-hand man. This was before Martin became a household name in The Wild Wild West, and you can see him honing that sidekick energy here. The chemistry between Vivyan and Martin is basically the heartbeat of the show. It’s a "buddy" dynamic before that became a tired trope. They weren't just business partners; they were two guys who genuinely seemed to enjoy the chaos of their lives.

The music? That’s the secret sauce. Henry Mancini. If you recognize that name, it’s probably because of the Pink Panther theme or "Moon River." For the Mr. Lucky TV series, Mancini composed a jazz-heavy score that was so popular the soundtrack album actually hit the top of the charts. Think about that for a second. A television soundtrack was competing with pop stars. That was the power of the "lounge" aesthetic back then.

Why It Was Canceled (The Real Story)

People often wonder why a show with good ratings and a massive cultural footprint got the axe after only thirty-four episodes. It wasn't because people stopped watching. It was actually because of a massive shift in the advertising world and a bit of moral panic.

💡 You might also like: Ashley My 600 Pound Life Now: What Really Happened to the Show’s Most Memorable Ashleys

The show was originally sponsored by Lever Brothers and Lifebuoy. But here’s the kicker: the mid-to-late fifties were a weird time for gambling on screen. The "payola" scandals and the general crackdown on quiz shows made networks twitchy about anything involving games of chance. Even though Lucky was the "good guy," the powers that be decided they wanted the gambling gone.

So, halfway through the season, the Fortuna was turned into a regular restaurant. No more dice. No more roulette. Just food.

It killed the vibe.

Imagine taking the "spy" out of a spy thriller and making the lead character a librarian. It just didn't work. The sponsor, Lever Brothers, eventually pulled out because they wanted a show that appealed more to women—the primary buyers of soap—and Mr. Lucky was decidedly a "guy’s show." Despite the efforts to save it, the show folded. It remains one of the great "what ifs" of early television history.

The Visual Language of Blake Edwards

If you watch an episode today, the first thing you’ll notice is the lighting. It’s noir. Deep shadows. Bright whites. It looked expensive. Most TV shows in 1959 were shot like stage plays—flat and functional. Edwards treated every episode like a miniature feature film. He used long takes. He let the camera linger on a glass of champagne or the reflection of the water on the hull of the boat.

📖 Related: Album Hopes and Fears: Why We Obsess Over Music That Doesn't Exist Yet

This wasn't accidental. Edwards was obsessed with the "sophisticated" look. He brought in cinematographer Guy Roe, who knew exactly how to make a low-budget TV set look like a million-dollar casino. You can see the lineage from this show directly to things like Ocean’s Eleven or even the more polished parts of the James Bond franchise. It was about an lifestyle as much as it was about a plot.

Lucky wasn't a superhero. He didn't have gadgets. He had his wits and a silver dollar that he would flip. Legend has it that John Vivyan actually had to practice that flip for hours because Edwards wanted it to look effortless. That’s the level of detail we’re talking about.

Where to Find It Today

Honestly, finding the Mr. Lucky TV series in high quality is a bit of a chore. It hasn't received the massive 4K restoration treatment that some of its contemporaries have. For a long time, it existed only in the memories of Boomers and on grainy bootleg tapes traded at conventions.

Eventually, it made its way to DVD via Timeless Media Group. If you can find that set, grab it. It’s the most complete version available. You might also find episodes rotating on classic TV networks like MeTV or Decades, though they tend to show up in the "graveyard" slots late at night.

A Legacy of Style

What’s fascinating is how the show influenced fashion. Men wanted those slim-cut suits. They wanted the narrow ties. The "Lucky look" was a precursor to the Mad Men era of style. It wasn't about being rugged; it was about being refined.

👉 See also: The Name of This Band Is Talking Heads: Why This Live Album Still Beats the Studio Records

There’s a specific episode, "The Money Game," where Lucky has to outmaneuver a guy who is essentially his dark mirror image. It’s a masterclass in tension. There are no explosions. No car chases. Just two men sitting across a table, talking. The stakes feel massive because the show spent so much time establishing that Lucky’s reputation was his most valuable asset. Once you lose your "luck," you lose everything.

Actionable Insights for Retro TV Hunters

If you’re looking to get into the show or explore this era of television, here is how you should approach it:

- Listen to the Score First: Before you even watch an episode, find the Mancini soundtrack on a streaming service. It sets the mood better than any trailer ever could.

- Watch the Pilot: "The Magnificent Guest" is the best entry point. It establishes the Fortuna and the central conflict perfectly.

- Look for Ross Martin’s Performance: Pay attention to how Martin handles the dialogue. He’s often the one providing the exposition, but he does it with such flair that you don't realize you're being "fed" information.

- Compare the Eras: Watch an episode from the first half of the season (the gambling era) and compare it to one from the end of the season (the restaurant era). You’ll see exactly why the show lost its steam.

- Check the Guest Stars: Like many shows of the time, Mr. Lucky featured actors who would go on to be huge. Look for appearances by people like Yvette Mimieux or Warren Oates.

The Mr. Lucky TV series isn't just a relic. It’s a snapshot of a moment when television was trying to figure out if it could be "cool" enough for adults. It proved that you didn't need a sprawling epic to capture an audience; you just needed a boat, a jazz score, and a guy who knew how to flip a coin.

Even though it’s been off the air for over sixty years, the ghost of the Fortuna still floats out there in the cultural ether. It reminds us that sometimes, being lucky is better than being good, but being both is the real trick.

To dig deeper into the world of Blake Edwards, your best bet is to look into his follow-up projects from the early sixties. Many of the crew members from Mr. Lucky moved directly onto his film sets, carrying that signature visual style into Hollywood's Golden Age. Seeking out the original 1943 film provides a startling contrast in tone that highlights just how much the TV version modernized the character for a New Frontier audience.