Wes Craven wasn't always the "Master of Horror" who gave us Freddy Krueger or the meta-commentary of Scream. In 1972, he was just a guy with a tiny budget and a lot of anger about the Vietnam War. When the movie Last House on the Left 1972 hit theaters, it didn't just scare people. It made them sick. Literally. People were reportedly fainting in the aisles or demanding their money back because what they saw wasn't the fun, gothic horror of Dracula or the Wolfman. It was something much more mean-spirited.

The movie follows two teenage girls, Mari and Phyllis, who head into the city for a concert and end up crossing paths with a group of escaped convicts. What happens next is a grueling, grainy sequence of events that basically pioneered the "exploitation" genre. But if you look past the low-budget grime, there’s a weirdly sophisticated core to it.

The Bergman Connection Nobody Expected

Most people watching a drive-in horror flick in the early seventies weren't exactly looking for Swedish art-house references. But honestly, Wes Craven and producer Sean S. Cunningham basically remade Ingmar Bergman’s The Virgin Spring (1960). It’s the same plot. A young girl is murdered, and her parents take a brutal, calculated revenge on the killers when they unknowingly seek shelter at the family home.

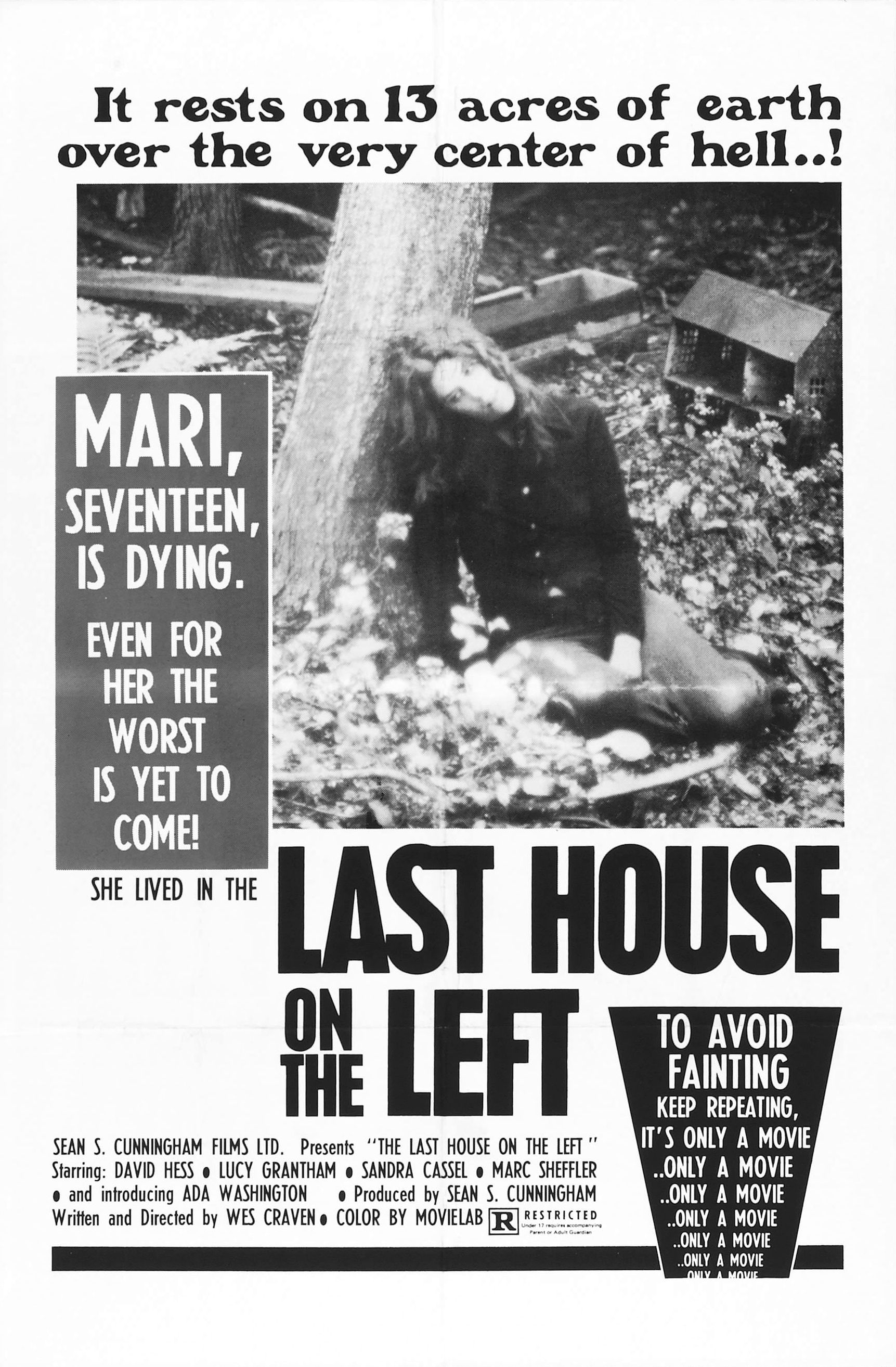

Craven took that high-brow premise and dragged it through the mud of 1970s American nihilism. While Bergman’s film wrestled with God and silence, Last House on the Left 1972 wrestled with the fact that "nice" people are capable of becoming monsters if you push them hard enough. It’s a cynical view. The tagline "To avoid fainting, keep repeating, 'It's only a movie...'" became one of the most famous marketing gimmicks in history, but for many, it didn't help.

The acting is uneven, sure. But David Hess, who played the lead villain Krug, brings this terrifying, unpredictable energy that feels dangerously real. He wasn't a slasher villain with a mask; he was just a guy who looked like your neighbor if your neighbor was a sociopath.

📖 Related: The A Wrinkle in Time Cast: Why This Massive Star Power Didn't Save the Movie

Why the Movie Last House on the Left 1972 Felt So Different

If you watch it now, the film looks dated. The blood is the color of bright red paint. The soundtrack is—and I’m being serious here—bizarrely upbeat in places. David Hess actually wrote and performed the music, and having a folk-pop song playing while someone is being stalked creates this jarring, surreal dissonance that makes the violence feel even more wrong.

That was the point.

Craven wanted to strip away the "safety" of cinema. In 1972, the evening news was showing actual footage from Vietnam. People were seeing death on their TV screens every night during dinner. Craven felt that the horror movies of the time were too polite. He wanted to show that violence isn't cinematic or cool. It’s messy, it’s humiliating, and it leaves everyone involved—victims and perpetrators—totally hollow.

The Censorship Wars

The movie Last House on the Left 1972 has a legendary history with the censors. In the UK, it was famously banned as a "video nasty." The BBFC (British Board of Film Classification) refused to give it a certificate for decades. It wasn't until 2002 that the film was finally released uncut in Britain. Think about that. It took thirty years for the government to decide adults could handle this movie.

👉 See also: Cuba Gooding Jr OJ: Why the Performance Everyone Hated Was Actually Genius

Even in the States, it was a nightmare. Theater owners would often cut out the most offensive parts themselves, leading to dozens of different versions of the film floating around. Some prints were missing the infamous "chainsaw" finale, while others were trimmed to avoid an X rating.

Breaking the Rules of Storytelling

Most movies have a "hero." This one doesn't. Not really. When Mari’s parents, the Collingwoods, realize who is in their house, they don't call the police. They turn into the very thing they hate. The father, played by Gaylord St. James, uses a chainsaw. It’s a total breakdown of the "civilized" family unit. This was shocking back then because it suggested that the "moral" suburbs were just a thin veneer over primal savagery.

There is a subplot involving two bumbling police officers that almost feels like it belongs in a different movie. It's goofy. It’s slapstick. Most critics hate it. But some film historians, like Kim Newman, have suggested this was Craven's way of showing how useless authority is when real evil shows up. The cops are literally a joke while the tragedy is unfolding.

The Lasting Legacy and the 2009 Remake

When they remade the film in 2009, they cleaned it up. The production values were higher, the acting was more "professional," and the gore was more realistic. But it lost the soul of the original. The 1972 version feels like a snuff film found in an attic. That graininess gives it a documentary-like quality that makes it harder to watch than a high-definition 4K horror movie today.

✨ Don't miss: Greatest Rock and Roll Singers of All Time: Why the Legends Still Own the Mic

It influenced everything that came after it. Without Last House on the Left 1972, you probably don't get The Texas Chain Saw Massacre or The Hills Have Eyes. It proved there was a market for "uncomfortable" cinema. It wasn't about the jump scares; it was about the dread that sits in your stomach for three days after the credits roll.

Things to Look For if You Watch It (Or Rewatch It)

- The Tone Shifts: Notice how the movie flips from comedy to horrific violence in seconds. It’s meant to keep you off-balance.

- The Soundtrack: Listen to David Hess's lyrics. They are often describing what's happening on screen but in a weirdly poetic, detached way.

- The Setting: The woods feel claustrophobic despite being outdoors. It’s a masterclass in low-budget location scouting.

- The Ending: Look at the faces of the parents after their "victory." They don't look relieved. They look destroyed.

If you’re a horror fan, you kind of have to see the movie Last House on the Left 1972 at least once, even if you hate it. It’s a piece of history. It represents the moment horror stopped being about monsters under the bed and started being about the monsters living in the house next door. Or, more accurately, the monsters living inside us.

To truly understand this era of film, you should compare it to the "Video Nasty" era in the UK or look into the "Slasher" boom of the early 80s that followed. The jump from this film to Halloween is massive, showing how the genre moved from raw exploitation back into stylized suspense. If you want to dive deeper, look up the documentary Celluloid Bloodbath or read Wes Craven's own interviews about his time working in the New York film industry during the early 70s. It was a gritty time, and it produced a gritty movie.

Check out the original theatrical trailer if you can find it online; it’s a masterclass in 70s exploitation marketing. After that, look for the "Krug and Company" alternate title sequences, which show how the movie was re-branded to try and trick audiences into seeing it twice. Understanding the distribution of this film is just as fascinating as the movie itself.