Honestly, if you grew up anytime in the last fifty years, you probably have a very specific image burned into your brain: a tiny mouse wearing a cut-out Ping-Pong ball as a helmet, gripping the handlebars of a red toy motorcycle. It’s iconic. But when you revisit The Mouse and the Motorcycle by Beverly Cleary as an adult, you realize it isn't just a "cute" animal story. It’s actually a pretty gritty look at independence, the risks of technology, and the weird, silent bond between kids and the hidden worlds they imagine.

Cleary published this in 1965. Think about that.

The world was changing, and children's literature was starting to move away from the hyper-moralistic "be a good boy" tropes of the fifties. Then comes Ralph S. Mouse. He isn't a hero. He’s a reckless, slightly selfish, and incredibly bored rodent living in a run-down hotel in California. He’s basically every teenager who ever wanted to steal their dad’s car keys.

The Mountain View Inn: A Masterclass in Setting

The story kicks off at the Mountain View Inn, a drafty, aging hotel in the Sierra Nevada Mountains. Cleary doesn't paint it as a luxury resort. It’s a place with threadbare carpets and "the smell of ancient dust." It's the perfect staging ground for a boy named Keith and a mouse named Ralph to cross paths.

Most people remember the bike, but they forget the logistics. Ralph lives behind the baseboards of Room 215. His family is constantly terrified of the vacuum cleaner—the "monster" that threatens their very existence. This isn't whimsical fluff; for a mouse, life is high-stakes survival. When Keith’s family checks in, Ralph spots the toy motorcycle on the nightstand. He doesn't just want it. He needs it.

It’s the ultimate symbol of speed and escape.

How the Magic Actually Works (It’s Not What You Think)

There is a very specific mechanic in this book that most AI or modern "fantasy" writers would over-explain with complex lore. In Ralph’s world, the motorcycle doesn't have an engine. It doesn't run on gas. To make it go, Ralph has to make the noise.

Pb-pb-b-b-b.

If he stops making the noise, the bike stops. This is a brilliant narrative device. It ties the "magic" directly to the imagination and the physical breath of the character. It’s a meta-commentary on how play works. If you stop believing in the game, the game ends. I've always found it fascinating that Cleary chose this over a "magic" bike that just works on its own. It makes Ralph’s agency—and his mistakes—completely his own.

🔗 Read more: Evil Kermit: Why We Still Can’t Stop Listening to our Inner Saboteur

The Reality of Ralph’s "Teenage" Rebellion

Ralph S. Mouse is a rebel. He’s tired of his mother worrying about him. He’s tired of the "crumbs" of life. When Keith lets him use the motorcycle, Ralph doesn't immediately become a hero. He almost dies in a wastebasket because he gets too cocky.

He loses the bike.

That’s a huge plot point that people tend to gloss over in their nostalgia. He loses Keith’s most prized possession in a pile of dirty laundry. The middle of the book is actually quite heavy with guilt. Ralph has to face the fact that his desire for speed and "coolness" had real-world consequences for the person who trusted him. It's a lesson in accountability that feels earned, not preached.

Why Beverly Cleary Was a Genius

Cleary didn't talk down to kids. She understood that a child’s world is full of small injustices and huge desires.

- She captured the specific frustration of being too small to reach things.

- She understood the transactional nature of friendship (Keith provides the bike/food; Ralph provides the wonder).

- The prose is lean. No fluff.

She once said in an interview with The Atlantic that she wrote the books she wanted to read as a child—books about "the sort of children who lived in my neighborhood." Even when she added a talking mouse, the emotions stayed grounded in that neighborhood reality.

The "Aspirin Run" and the Turning Point

The climax of The Mouse and the Motorcycle is the famous Aspirin Run. Keith gets a fever. His parents are worried. The hotel is out of aspirin, and the drugstores are closed. This is where Ralph moves from being a "taker" to a "giver."

He braves the vacuum cleaner, the hotel cat (a terrifying antagonist named Chirp), and the sheer distance of the hallways to bring a single tablet of aspirin to Keith. It’s a classic "hero's journey" compressed into the floorboards of a motel. He uses the motorcycle not for a joyride, but as a tool for a mission.

It’s the moment Ralph grows up.

💡 You might also like: Emily Piggford Movies and TV Shows: Why You Recognize That Face

Misconceptions About the Series

A lot of people think this is a standalone book. It’s actually the start of a trilogy. You’ve got Runaway Ralph (where he goes to a summer camp) and Ralph S. Mouse (where he goes to school).

Runaway Ralph is arguably darker. He ends up in a cage. It deals with the reality that "freedom" often comes with the price of loneliness. If you only read the first one, you’re missing the full arc of Ralph’s realization that the world is much bigger—and much more dangerous—than Room 215.

Another misconception: the 1986 TV movie. While it's a nostalgia trip (with that classic stop-motion animation), it simplifies a lot of the internal struggle Ralph feels. The book is much more focused on the internal monologue of a mouse who feels trapped by his biology.

The Legacy of the Red Motorcycle

Why does this book still sell? Why is it still on school reading lists in 2026?

Because it’s about the first taste of power.

For a kid, a bicycle is their first motorcycle. For Ralph, the toy is his. It represents the transition from being a passenger in life to being the driver. Cleary tapped into that universal human (and mouse) desire for autonomy.

If you’re looking for a deep dive into the technicalities of the writing, look at her verbs. She doesn't use "flowery" language. She uses "active" language. Ralph doesn't "move quickly"; he scampers, darts, and vibrates with energy.

Actionable Steps for Parents and Readers

If you're planning to introduce a new generation to The Mouse and the Motorcycle, or if you're revisiting it yourself, here is how to get the most out of the experience:

📖 Related: Elaine Cassidy Movies and TV Shows: Why This Irish Icon Is Still Everywhere

Read it aloud, but do the voices.

The book relies heavily on the sounds—the pb-pb-b-b-b of the motor. It was designed to be heard. If you aren't making the engine noises, you're doing it wrong.

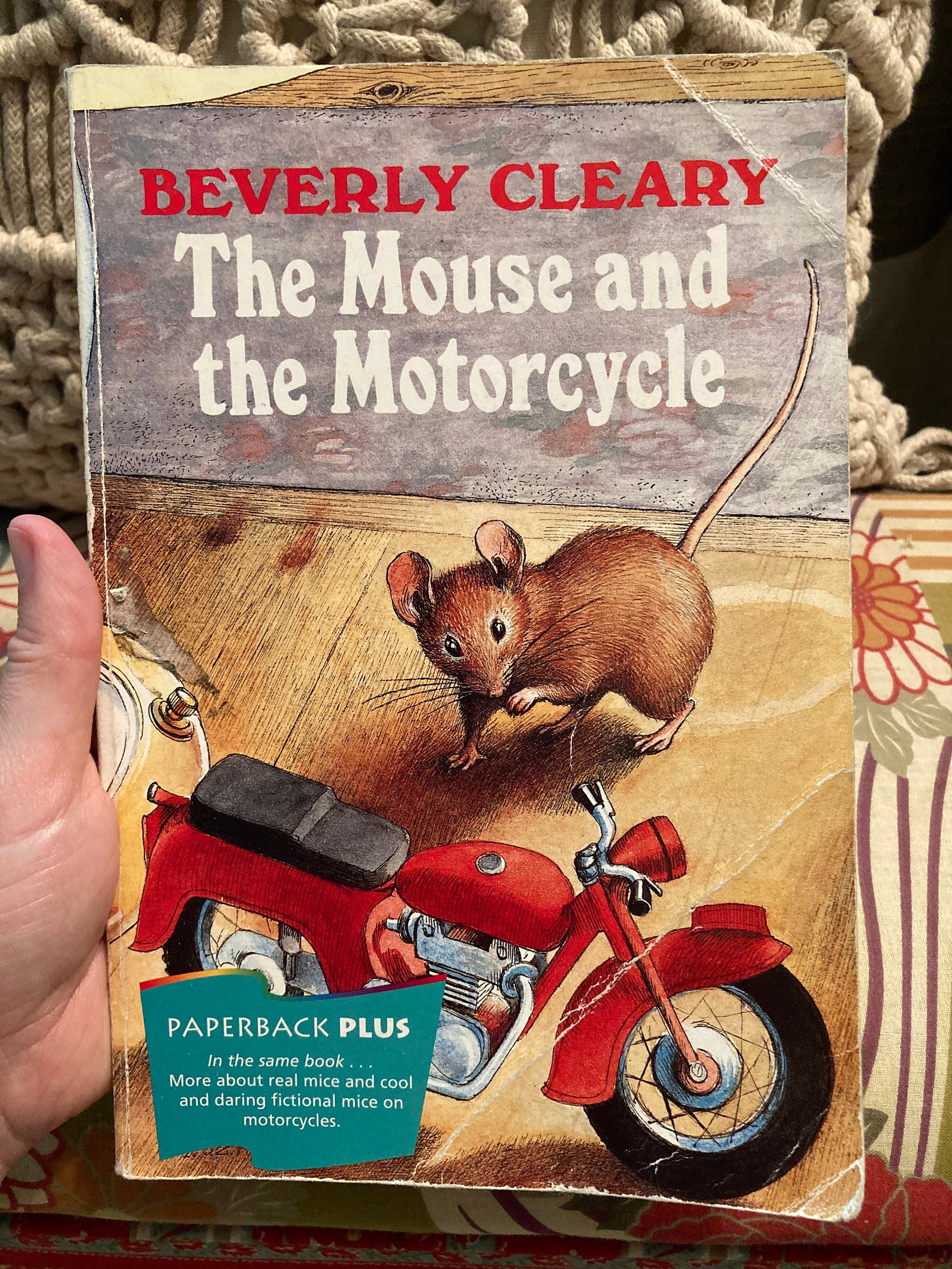

Look at the illustrations by Louis Darling.

While there have been many covers over the years, the original Darling illustrations captured the "heavy" feel of the toy motorcycle. It wasn't a cheap plastic toy; it was metal. It had weight. That weight is important to the story’s physics.

Discuss the ethics of the "deal."

Talk about whether Ralph was right to take the bike in the first place. It opens up great conversations with kids about boundaries and "borrowing" versus "stealing."

Visit an old roadside motel.

The Mountain View Inn is a character itself. If you’re ever on a road trip, find one of those old-school, two-story motels with exterior walkways. It makes the scale of Ralph's journey much more real when you see the length of a "standard" hotel hallway.

Check out the rest of the Cleary collection.

If Ralph clicks, move to Dear Mr. Henshaw. It's a completely different vibe—much more emotional and grounded—but it shows Cleary’s range. She wasn't just the "mouse lady." She was a chronicler of the American childhood experience.

The magic of Ralph isn't that he can talk or ride a bike. It's that he feels exactly like we do when we're stuck in a small room dreaming of the open road. He’s a tiny, furry reminder that adventure is usually just a pb-pb-b-b-b away.

Next Steps for Your Reading List:

- Secure a copy of the original 1965 edition (or a reprint with Louis Darling's art) to see the intended visual scale.

- Compare the themes of "mechanical imagination" in this book with The Borrowers by Mary Norton to see how different authors handle small-scale world-building.

- Track down the 1980s live-action/claymation adaptation for a masterclass in practical effects before the CGI era took over.