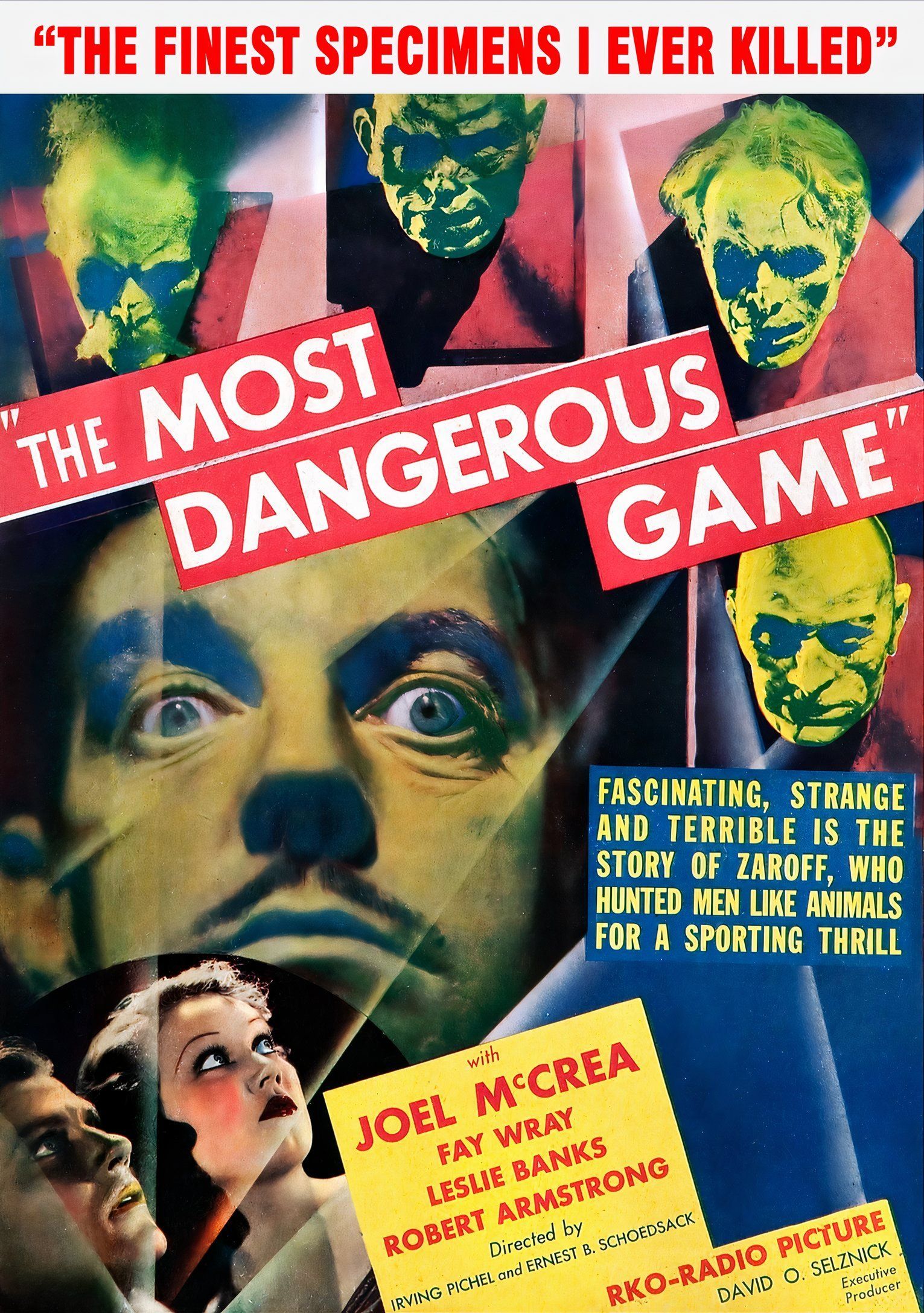

Pre-Code Hollywood was a wild, lawless frontier. Before the Hays Office started wagging its finger and censoring every drop of blood or hint of "immorality," filmmakers were doing things that would still make modern audiences flinch. The Most Dangerous Game 1932 is the poster child for this era. It’s lean. It’s mean. It’s barely an hour long, yet it manages to pack in more psychological dread and genuine "ick factor" than most three-hour modern blockbusters. Honestly, it’s kind of a miracle it even exists in the form it does.

If you’ve ever watched a movie where a group of people are hunted for sport—think The Hunger Games, The Hunt, or Hard Target—you’re looking at the DNA of this 1932 classic. But those movies usually have a political message or a social commentary angle. This one? It’s just pure, primal terror. It asks a simple, terrifying question: What happens when the world’s greatest hunter gets bored with animals and starts looking for a "more challenging" prey?

The RKO Connection and the King Kong Secret

Here is a bit of trivia that usually blows people’s minds: The Most Dangerous Game 1932 was filmed at the exact same time, on the exact same sets, as the original King Kong.

Think about that for a second.

Directors Ernest B. Schoedsack and Merian C. Cooper were basically pulling double shifts. They’d film the giant ape during the day and then switch over to the human-hunting-human story at night. They even used the same actors. Fay Wray, the legendary scream queen, is the lead in both. Robert Armstrong is in both. If the jungle in this movie looks familiar, that’s because it’s the same tangled, foggy mess that Kong called home. This wasn't just a cost-cutting measure; it gave the film a massive, big-budget atmosphere that most "B-movies" of the time couldn't touch.

The pacing is breathless. There’s no "fluff." You get a shipwreck, a mysterious island, and a creepy Russian Count within the first ten minutes. It doesn't waste your time with backstory that doesn't matter. It just drops you right into the nightmare.

Count Zaroff: The Villain Who Defined a Trope

Leslie Banks plays Count Zaroff, and man, is he unsettling. Most villains back then were either pantomime monsters or mustache-twirling caricatures. Zaroff is different. He’s sophisticated. He’s a "civilized" man who plays the piano and drinks fine wine, which makes his obsession with "the chase" even more revolting. He’s not a mindless killer; he’s a bored aristocrat.

📖 Related: Gwendoline Butler Dead in a Row: Why This 1957 Mystery Still Packs a Punch

He basically tells our hero, Sanger Rainsford (played by Joel McCrea), that he’s bored with hunting tigers because they can’t reason. He wants something that can think. Something that can fight back.

What’s truly wild is the way Zaroff talks about his "game." He calls it "the outdoor chess." There is a weird, sexualized undertone to his hunt that you just wouldn't see a few years later once the Production Code was strictly enforced. He’s not just looking for a kill; he’s looking for an experience. The way he looks at Fay Wray’s character, Eve, makes it very clear that the "prize" for winning the hunt isn't just survival—it’s her. It’s grimy. It’s uncomfortable. It’s effective.

Why the Pre-Code Era Mattered for This Story

If this movie had been made in 1935 instead of 1932, it would have been a totally different (and worse) film.

In the actual 1932 version, we see "trophy rooms" that aren't just filled with animal heads. There are human heads in jars. There’s a directness about the violence and the stakes that feels very modern. The filmmakers didn't have to hide the Count’s true intentions behind metaphors. They just showed it.

The special effects for the time were actually pretty groundbreaking. The matte paintings and the way they layered the shots created a sense of scale that was rare. But the real star is the atmosphere. The island feels like a living, breathing trap. The "Great Swamp" sequence is a masterclass in tension, using sound design (the squelching mud, the distant dogs) to do the heavy lifting.

The Most Dangerous Game 1932 vs. The Short Story

Most people read Richard Connell’s original short story in middle school. It’s a staple of English class. But the movie makes some massive changes, and for once, they actually work.

👉 See also: Why ASAP Rocky F kin Problems Still Runs the Club Over a Decade Later

In the story, Rainsford is alone. In the movie, they added Eve and her brother. This was a smart move for a few reasons:

- It raises the stakes. Rainsford isn't just saving his own skin; he’s protecting someone else.

- It gives Zaroff a clearer motivation (his creepy obsession with Eve).

- It allows for dialogue that explains the Count’s twisted philosophy without it being a lonely monologue.

Some purists might hate the addition of a female lead just to have a "damsel," but Fay Wray isn't just a prop. She’s the one who first notices things are wrong. She’s the one who finds the "trophy room." She’s the catalyst for the escape.

Why We Are Still Obsessed With the Hunter/Hunted Dynamic

There is something deeply baked into the human psyche about the fear of being hunted. It’s our oldest nightmare. The Most Dangerous Game 1932 tapped into that better than almost any film since.

Look at Predator. Look at Squid Game.

They all owe a debt to this 63-minute movie. The idea that "civilization" is just a thin veneer and that underneath it all, we are just animals is a theme that never gets old. Rainsford starts the movie as a callous hunter who doesn't believe animals feel fear. By the end, he is the animal. The irony isn't subtle, but it's powerful.

Interestingly, the movie was actually banned in some countries upon release because it was deemed too disturbing. Even in the U.S., it was edited down for re-releases to meet the newer, stricter moral standards of the late 30s. We are lucky to have the restored versions today that show the Count in all his twisted glory.

✨ Don't miss: Ashley My 600 Pound Life Now: What Really Happened to the Show’s Most Memorable Ashleys

Technical Brilliance in a Tiny Package

The cinematography by Henry Gerrard is surprisingly experimental. He uses "wipes"—where one scene literally slides off the screen to reveal the next—in a way that feels like a comic book. This gives the film a pulpy, fast-paced energy.

Then there's the score by Max Steiner. This was one of the first films to have an extensive "wall-to-wall" musical score. Before this, movies were often quite quiet, with music only used during titles or specific scenes. Steiner (who also did King Kong) used the music to tell the story, with specific themes for the hunt and for the Count. It’s grand, operatic, and slightly over-the-top, which fits the gothic vibe perfectly.

Common Misconceptions About the 1932 Version

A lot of people think this is a "silent movie" because of the year. It’s not. It’s a full "talkie" and uses sound quite brilliantly. Another misconception is that it's a slow, plodding drama. Honestly, it’s the opposite. It’s faster than most modern action movies.

Some people also confuse it with the dozens of remakes and "inspired by" films. There was A Game of Death in 1945 and Run for the Sun in 1956. None of them capture the specific, nightmare-logic intensity of the 1932 original. There is a grit to the black-and-white film stock that makes the jungle feel much more dangerous than a color version ever could.

Actionable Insights for Film Buffs and Horror Fans

If you’re going to watch The Most Dangerous Game 1932, don't just treat it like a museum piece.

- Watch the Criterion Collection or a high-quality restoration. The grainy, low-res YouTube versions don't do justice to the incredible set design and lighting. You need to see the detail in the Count's fortress to appreciate the "Gothic" feel.

- Pay attention to the sound. Listen to how they use silence in the jungle vs. the booming music in the castle. It's a lesson in tension-building.

- Compare it to the story. If you haven't read Richard Connell's story in a while, give it a quick re-read before or after. The differences in Rainsford's character are fascinating. In the story, he's much more cold-blooded.

- Look for the Kong sets. Seriously, it’s a fun game to try and spot the log bridge or the specific rock formations that appear in the King Kong movie.

The film is a reminder that you don't need a $200 million budget or CGI monsters to terrify an audience. You just need a compelling hook, a truly charismatic villain, and a deep understanding of the human fear of the dark.

Whether you're a student of film history or just someone looking for a creepy late-night movie, this film delivers. It’s a lean, mean, hunting machine of a movie that hasn't lost its edge in nearly a century. If you haven't seen it, you're missing out on the blueprint for the entire "survival horror" genre. Just remember: stay off the mud flats at night, and never, ever trust a man with a private island and a collection of human-sized jars.

To truly appreciate the evolution of this genre, your next step should be a double feature. Watch this 1932 classic and then jump straight to 1987's Predator. You'll see exactly how the "rules of the game" established by Count Zaroff are still being followed today, shot for shot, trap for trap.