It’s almost a century later, and we're still arguing about the same things. Honestly, if you pick up a copy of The Mis-Education of the Negro today, it feels less like a history book and more like a mirror. A very loud, very honest mirror. Carter G. Woodson didn’t just write a critique of the American school system back in 1933; he basically performed a forensic autopsy on the psyche of a people who were being taught to hate themselves.

Think about that for a second.

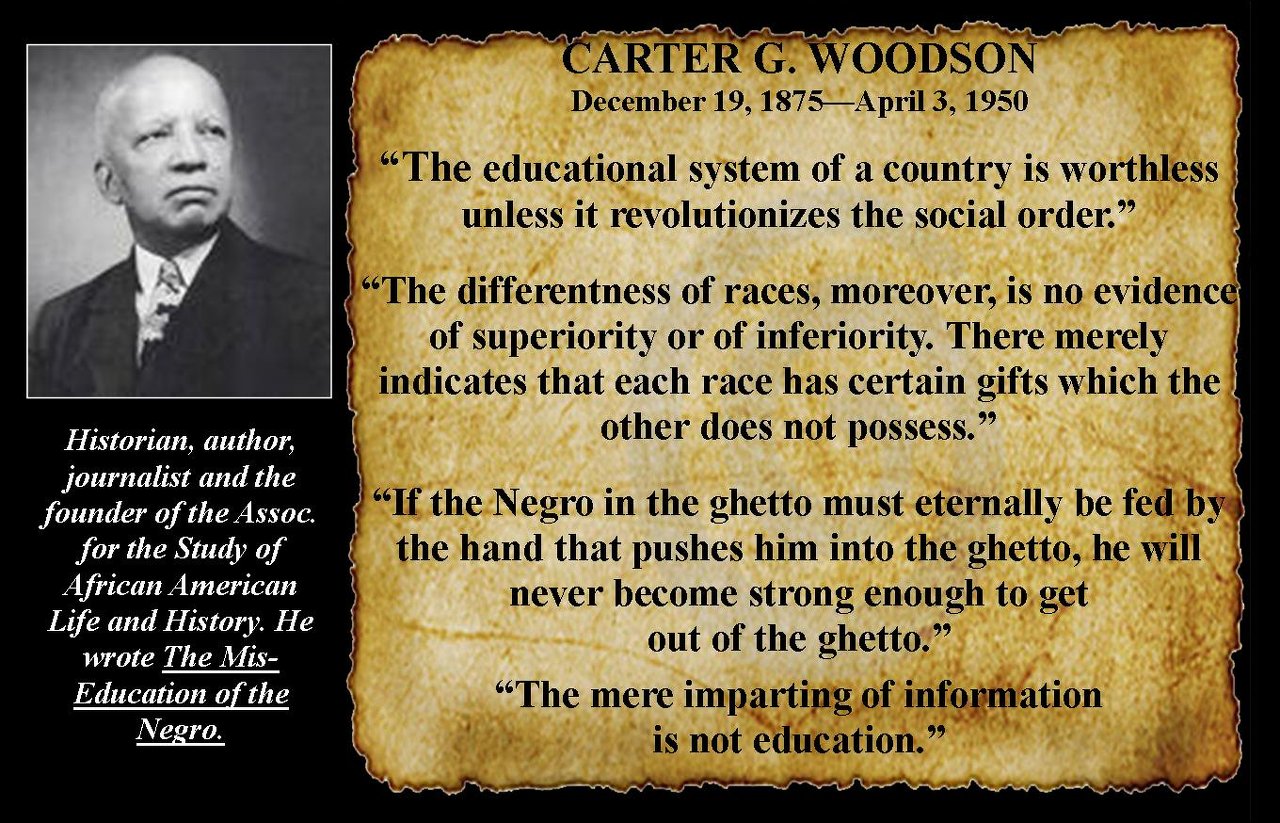

Woodson was the second Black person to ever get a PhD from Harvard. He wasn't some outsider looking in. He was a man who had mastered the highest levels of "white" education only to realize that the system was fundamentally broken for people like him. He saw that the more "educated" Black people became in these traditional institutions, the more they seemed to drift away from their own communities. They were becoming strangers to their own kin.

The Core Conflict in The Mis-Education of the Negro

Woodson’s big realization was pretty simple but devastating. He argued that if you control a man’s thinking, you don't have to worry about his actions. You don't have to tell him to stand back or go to the back door. He will go there without being told. And if there is no back door, he will cut one out for his special benefit.

It’s heavy stuff.

The central thesis of The Mis-Education of the Negro isn't just about bad textbooks or missing history. It’s about the psychological conditioning that happens when a curriculum ignores your existence or, worse, mentions you only as a problem to be solved or a victim to be pitied. Woodson noticed that Black students were being taught to admire the accomplishments of others while being told—implicitly or explicitly—that they had none of their own. This created a weird kind of "highly trained" person who could solve complex math problems but couldn't figure out how to build a business in their own neighborhood.

Woodson was looking at the 1930s, but you've gotta wonder how much has actually changed. We still see the same patterns. Students go through sixteen years of schooling and might only hear about Black people during February. And even then, it’s usually just a highlight reel of the Civil Rights Movement. It’s "Rosa sat, Martin stood, and then everything was fine." Woodson would have hated that. He argued that this kind of superficial "inclusion" is just another form of miseducation because it doesn't give you the tools to actually change your reality.

🔗 Read more: Anime Pink Window -AI: Why We Are All Obsessing Over This Specific Aesthetic Right Now

Why the "Talented Tenth" Failed the Community

You’ve probably heard of W.E.B. Du Bois and his idea of the Talented Tenth. He thought the top 10% of Black people would lead the rest to freedom through education and leadership. Woodson wasn't so sure. In The Mis-Education of the Negro, he actually takes a pretty hard swing at the Black elite of his time.

He noticed a trend.

The more degrees these folks got, the more they looked down on the "uneducated" masses. They wanted to move away. They wanted to distance themselves from the struggle. Woodson saw this as a tragedy. He believed that education should make you more useful to your community, not more ashamed of it. He writes about how the educated Black man would rather spend his money at a white business that discriminates against him than support a Black business owner who didn't go to college.

It’s a cycle of self-sabotage.

Woodson wasn't just complaining, though. He was obsessed with the idea of "industrial" versus "classical" education. He didn't think one was better than the other, but he thought both were being taught wrong. If you teach a man to be a plumber but don't teach him how to own the plumbing company, you’ve just trained a servant. If you teach a man to be a philosopher but he can't fix his own sink, he’s useless in a crisis. Woodson wanted a marriage of the two: high-level thinking paired with practical, community-building skills.

The Psychological Trap of the "Back Door"

Let’s talk about that "back door" quote again because it’s the most famous part of the book for a reason. Woodson was describing a mental state. When the education system teaches you that you are inferior, you start to internalize that. You start to seek permission for things you should just do.

💡 You might also like: Act Like an Angel Dress Like Crazy: The Secret Psychology of High-Contrast Style

Basically, it's about agency.

If you don't know your own history—real history, not the watered-down version—you don't know what you're capable of. You end up waiting for someone else to give you a job, a house, or a right. Woodson's whole point was that true education is about self-liberation. It’s about looking at the world and realizing you have the power to reshape it.

He was incredibly frustrated with how the church was functioning at the time, too. He felt many ministers were miseducated themselves, teaching a version of Christianity that focused only on the afterlife while ignoring the poverty and injustice happening right outside the church doors. He wanted a "social gospel" that actually addressed the needs of the people. This wasn't about being anti-religious; it was about being pro-reality.

The Problem with "Standardized" Success

Woodson’s critique of the 1930s education system feels eerily similar to modern critiques of standardized testing and "one size fits all" schooling. He saw that the system was designed to produce workers, not thinkers. Specifically, it was designed to produce workers who wouldn't challenge the status quo.

When you look at The Mis-Education of the Negro through a 2026 lens, you see the roots of what we now call "culturally responsive teaching." Woodson was advocating for that before it had a fancy name. He believed that if you start with the student's own life, their own community, and their own heritage, they will be much more engaged and successful. It seems obvious, right? But it was radical then, and in some places, it’s still radical now.

There’s this misconception that Woodson just wanted Black people to learn about Black history. It’s more than that. He wanted everyone to learn the truth. He argued that white people were also being miseducated because they were being taught a false sense of superiority that prevented them from seeing the world clearly. Miseducation, in his view, was a collective American disease. It’s just that Black people were the ones dying from it.

📖 Related: 61 Fahrenheit to Celsius: Why This Specific Number Matters More Than You Think

What We Get Wrong About Woodson Today

A lot of people think The Mis-Education of the Negro is just a "pro-Black" book. It is, but it’s also a "pro-truth" book. Woodson wasn't interested in fairy tales. He was a historian. He founded the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (now ASALH) because he wanted the facts. He wanted the records. He wanted the evidence of what people had actually built, written, and fought for.

Some critics today might say Woodson was too hard on his own people. He definitely didn't pull any punches. He criticized the lack of business sense, the imitation of white society, and the "parasitic" nature of some leaders. But he did it because he cared. He saw the potential of the Black community and was devastated by how it was being wasted.

It’s also important to remember that Woodson wasn't saying "don't go to school." He was saying "don't let school happen to you." He wanted people to be critical consumers of information. If a textbook says something that contradicts your lived experience or the evidence you see with your own eyes, question it. That’s what a real education looks like.

Actionable Lessons from Woodson’s Philosophy

So, what do we actually do with this? If you’re feeling "miseducated" or just want to break out of the cycle Woodson described, here’s how you actually apply his work in the real world:

- Audit Your Sources: Stop relying on a single narrative. If you’re learning about history, economics, or even art, look for the voices that are usually left out. Woodson was all about finding the "hidden" records.

- Support Community Infrastructure: Woodson was big on economic self-sufficiency. Before you spend money at a massive corporation, see if there’s a local business or a community-owned alternative.

- Be a Critical Thinker, Not a Memo-Repeater: If you can repeat a fact but can’t apply it to solve a problem in your own neighborhood, you’re just "trained," not "educated." Focus on skills that create value for the people around you.

- Teach the Next Generation Early: Don't wait for the school system to give your kids the full story. Supplement their education with books, stories, and experiences that reflect their heritage and the diversity of the human experience.

- Reconnect with "Uneducated" Wisdom: Some of the smartest people Woodson knew didn't have degrees. They had "mother wit" and survival skills. Don't let your education make you too proud to learn from the people who actually keep the world running.

Woodson’s work is a call to action. It’s a reminder that freedom starts in the mind. If you haven't read it lately, go grab a copy—the real one, not just the quotes you see on Instagram. It’s uncomfortable, it’s challenging, and it’s exactly what we need if we’re ever going to stop cutting our own back doors.