The LGM-30 Minuteman III is old. Honestly, it’s ancient in tech years. Most of the hardware sitting in those reinforced concrete silos across the Great Plains was installed during the Nixon administration, and yet, it remains the backbone of the American land-based nuclear triad. It’s a strange, terrifying, and technically fascinating piece of Cold War engineering that just won't quit.

You’ve probably seen the photos of the boring white tubes. They look like something out of a 1960s sci-fi flick. But there is nothing boring about a three-stage solid-fuel rocket that can travel 6,000 miles and hit a target with terrifying precision. We're talking about a machine that accelerates to 15,000 miles per hour. That’s Mach 23.

The Aging Giant in the Room

People often ask why we are still using the LGM-30 Minuteman III when your iPhone has more computing power than the entire missile wing at Malmstrom Air Force Base. It’s a valid question. The tech inside these missiles is so old that the Air Force famously used 8-inch floppy disks up until 2019 to coordinate some of the functions.

They finally upgraded to secure digital chips, but the core architecture is still deeply analog. Why? Because you can’t hack an analog system from a laptop in a basement across the world. There's a brutal, functional simplicity to it.

The Minuteman III was the first Multiple Independently Targetable Reentry Vehicle (MIRV) missile. In its heyday, one rocket could carry three separate warheads, each headed for a different city or military base. Under current arms control treaties, specifically the New START treaty, they’ve been "downloaded" to carry just a single warhead, usually the W78 or the W87.

What’s actually under the hood?

Inside that 60-foot frame, you have three stages of solid rocket motors. Unlike liquid-fueled rockets—think of the old Soviet R-7 or even a SpaceX Falcon 9—solid fuel is stable. It stays in the missile, ready to go at a second’s notice. You don’t have to spend hours fueling it while a satellite watches from above. You just turn the keys.

The guidance system is where things get really "vintage." The NS50 missile guidance system uses a gyro-stabilized platform. It doesn't use GPS. You can’t jam it. It relies on Newtonian physics—accelerometers and gyros—to know exactly where it is in space relative to where it started.

Life in the Missile Fields

If you ever drive through North Dakota, Wyoming, or Montana, you’ll see them. Well, you won't see the missiles, but you’ll see the fences. Small, rectangular plots of land with some antennas and a heavy concrete slab. Underneath that slab sits the LGM-30 Minuteman III, kept at a constant temperature, monitored 24/7 by Missile Combat Crews.

These crews are young. Often in their early 20s. They spend 24-hour shifts underground in a "capsule" that looks like a relic from the set of Dr. Strangelove. It’s a high-pressure, low-glitz job. They call themselves "Missileers."

There’s a common misconception that these guys are just waiting to push a big red button. It’s not a button. It’s a series of switches and keys that must be turned simultaneously by two different people located in different parts of the capsule. This is the "Two-Man Rule." It’s a fail-safe against a single person having a mental breakdown and starting World War III.

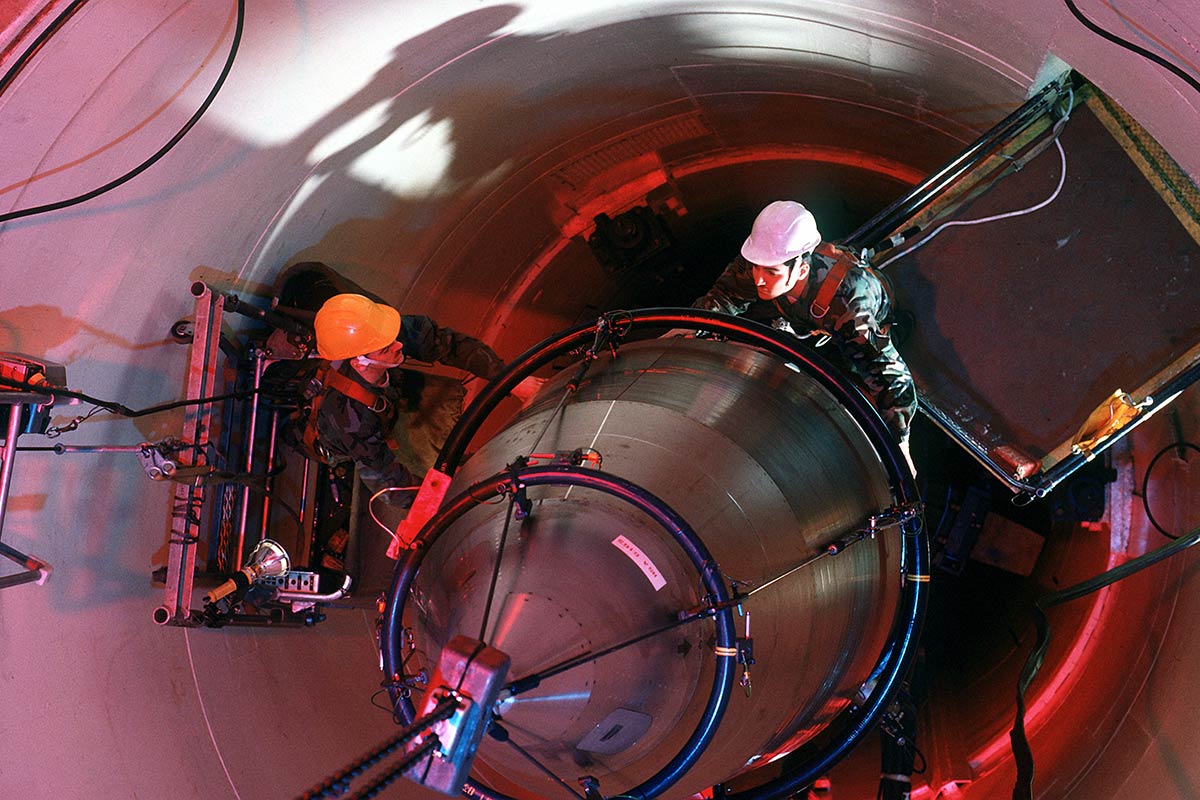

The Maintenance Nightmare

Keeping a 50-year-old missile ready to fire is a logistical headache that would make a Master Mechanic weep. The Air Force Global Strike Command spends billions of dollars on what they call "Sustainment."

Parts break. Companies that made the original gaskets or circuit boards went out of business forty years ago. Sometimes, the Air Force has to "cannibalize" parts or hire specialized firms to reverse-engineer components from scratch.

- Propellant aging: Over decades, solid fuel can crack or pull away from the casing.

- Corrosion: Water is the enemy of a steel silo buried in the dirt.

- Obsolescence: Finding technicians who understand the specific coding languages used in the 70s is getting harder every year.

The Sentinel Transition

The LGM-30 Minuteman III isn’t going to live forever. The replacement is already in the works: the LGM-35A Sentinel. But the transition is messy. It’s expensive. Some estimates suggest the overhaul will cost upwards of $100 billion.

Critics argue that we don't even need land-based missiles anymore. They say submarines are stealthier and bombers are more flexible. They call the Minuteman III silos "targets" because their locations are public knowledge. If a nuclear war starts, these silos are the first things the other side hits.

But proponents of the "Triad" disagree. They argue that having 400 separate targets spread across the Midwest creates a "targeting problem" for an enemy. You can't just take out one submarine; you have to hit 400 individual silos simultaneously. That’s the deterrent. It’s about making the cost of an attack too high to calculate.

🔗 Read more: How Do I Find Who Is Calling Me: The Real Truth About Reverse Phone Lookups

Security and the "Broken Arrow" Fears

There have been scares. In 2008, the Air Force accidentally shipped four MK-12 forward adapter sections (part of the Minuteman's reentry system) to Taiwan instead of helicopter batteries. Then there was the 2014 cheating scandal where missileers were caught sharing answers on proficiency tests.

These incidents remind us that the LGM-30 Minuteman III is a human system as much as a mechanical one. The tech might be cold and indifferent, but the people managing it are susceptible to boredom, fatigue, and error.

Despite the drama, the safety record of the actual warheads is remarkably robust. The Permissive Action Links (PALs) and the specialized "Environmental Sensing Devices" ensure that these things cannot detonate unless they experience the specific physical forces of a launch and a flight through space. You could drop a hammer on one, and it wouldn't go off. Probably don't try that, though.

Why We Should Pay Attention

The Minuteman III is a survivor. It outlasted the USSR. It outlasted the Cold War. Now, it finds itself in a new era of "Great Power Competition" with a rising China and a resurgent Russia.

It’s a bizarre paradox: the most powerful weapon in the American arsenal is also one of its oldest. It sits in the dirt, silent, waiting, and hopefully, it will stay that way until the last one is finally dismantled and replaced by the Sentinel.

Understanding this missile isn't just for military buffs. It’s about understanding the reality of global security. We live in a world where peace is maintained by the threat of "Prompt Global Strike"—the ability to put a warhead on any doorstep on Earth in 30 minutes or less.

Understanding the Specs (The Real Numbers)

To get a sense of the scale, you have to look at what this thing actually does during a flight. It's not just a straight line.

The Boost Phase

The first stage burns for about 60 seconds. It’s a massive kick that gets the missile out of the silo and into the upper atmosphere. The second and third stages take over in sequence, shedding weight as they go. By the time the third stage is done, the "bus"—the part carrying the warhead—is in space.

The Mid-course Phase

This is where the LGM-30 Minuteman III does its real work. It coasts through the vacuum of space in a ballistic arc. At this point, it’s traveling at its maximum velocity. It’s high above the atmosphere, far above where any airplane could ever reach.

The Reentry Phase

As gravity pulls the warhead back down, it hits the atmosphere at incredible speeds. The heat shield has to withstand temperatures that would melt almost any other material. It’s a white-hot streak across the sky. From launch to impact: roughly 30 minutes.

How to Track the Future of the Minuteman

If you want to keep tabs on what’s happening with these relics, there are a few things you can do. The military doesn't keep everything secret; they actually want people to know the deterrent is working.

- Watch for "Glory Trip" launches. A few times a year, the Air Force pulls a random Minuteman III from a silo, hauls it to Vandenberg Space Force Base in California, and launches it toward the Kwajalein Atoll in the Pacific. They do this to prove the old birds still fly. These launches are usually announced a day or two in advance.

- Monitor the NDAA (National Defense Authorization Act). This is where the budget for the Sentinel replacement lives. If you see the budget for "GBSD" (Ground Based Strategic Deterrent) fluctuating, you're seeing the political battle over the future of the Minuteman.

- Visit a Museum. If you want to see one up close without being tackled by security, go to the National Museum of the United States Air Force in Dayton, Ohio. They have a Minuteman III on display. It's much bigger in person than it looks in photos.

- Follow Global Strike Command. Their official press releases often detail the "Sustainment" efforts. It's a great way to see how they are dealing with the aging electronics and the transition to the LGM-35A.

The LGM-30 Minuteman III is a haunting piece of history that happens to still be active. It represents a different era of engineering—one where things were built to last decades under the most extreme conditions imaginable. Whether you view it as a necessary evil or an outdated relic, its presence in the American landscape is undeniable.