If you look at a middle colonies map today, it looks like a simple bridge. It’s that strategic stretch of land connecting the icy New England winters to the sprawling tobacco plantations of the South. But back in the 1700s? It was chaos. It was a messy, loud, multi-ethnic experiment that shouldn't have worked, yet somehow became the blueprint for the United States.

Geography is destiny. You’ve probably heard that before. In the case of New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware, it’s actually true.

The Weird Geography of the Middle Colonies Map

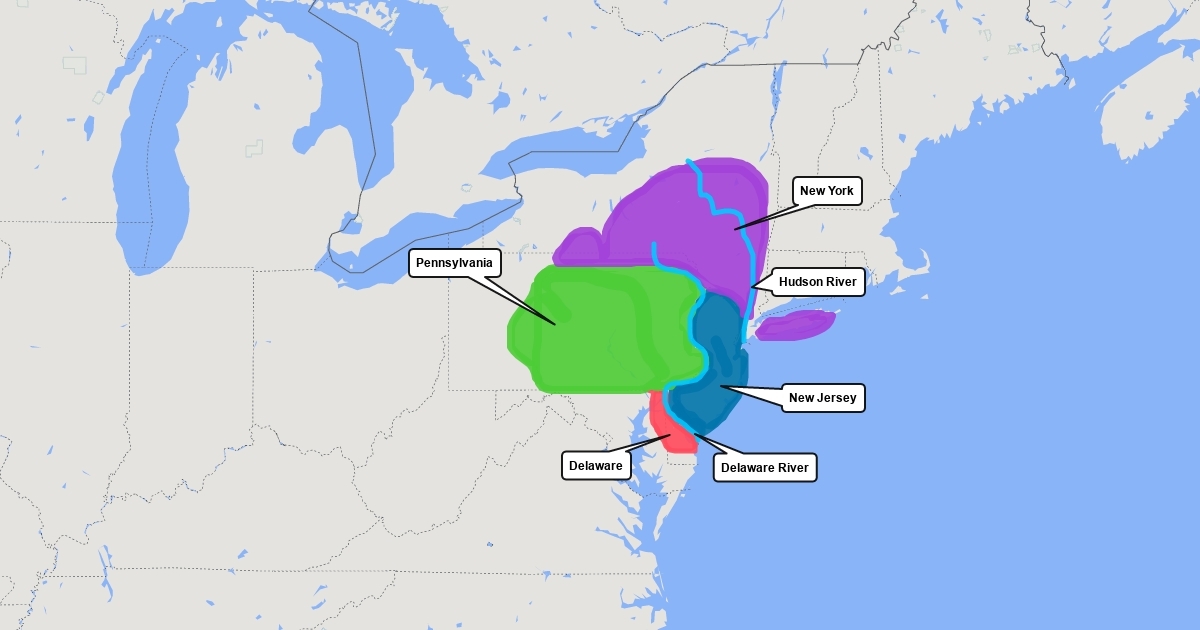

Most people glance at a map of the four middle colonies and see four distinct shapes. But the real story is in the water. Look closely at the Hudson, the Delaware, and the Susquehanna rivers. These weren't just lines on a page; they were the superhighways of the 18th century.

Unlike the rocky, unforgiving soil of Massachusetts or the swampy, malaria-prone lowlands of Virginia, the middle colonies hit the geological jackpot. The soil was deep. It was rich. Glacial shifts thousands of years prior had dumped a layer of fertile silt across the region that made it the "Breadbasket" of the Atlantic world.

Think about the sheer scale of it.

While a farmer in Connecticut was struggling to clear enough stones to plant a row of corn, a farmer in the Schuylkill Valley was exporting thousands of bushels of wheat to the Caribbean. The middle colonies map reveals a massive network of river valleys that fed directly into two of the finest natural harbors on the planet: New York City and Philadelphia.

It was a logistical dream.

Philadelphia vs. New York: A Tale of Two Ports

If you trace the coastline on a middle colonies map, your eye naturally stops at those two massive hubs. They weren't just cities; they were competing philosophies.

Philadelphia was the brainchild of William Penn. He wanted a "Greene Country Towne." He designed it on a grid—which you can still see on any modern street map—to prevent the cramped, fire-prone conditions of London. By the mid-1700s, it was the largest city in British North America. It was the intellectual heart of the continent.

New York was different. It was scrappy. It was originally New Amsterdam, a Dutch trading post, and it never quite lost that "money-first" attitude even after the English took over in 1664. When you look at the tip of Manhattan on a historical map, you’re looking at the most valuable real estate in the colonies.

The Dutch influence is the secret sauce here.

They brought a level of religious tolerance that was unheard of in the 1600s. While the Puritans in the North were busy banishing anyone who disagreed with them, the Dutch in New York (and later the Quakers in Pennsylvania) basically said, "We don't care who you pray to, as long as your money is good."

💡 You might also like: Finding the most affordable way to live when everything feels too expensive

That’s why the ethnic makeup of the middle colonies map was so diverse. You had English, Dutch, German, Scots-Irish, French Huguenots, and enslaved Africans all shoved into the same geographic space.

It was the original melting pot. Sorta.

The Breadbasket Reality

Grain. It sounds boring, right? But grain built the middle colonies.

Because the climate was temperate—neither too hot nor too cold—the growing season was long enough to produce massive surpluses. This changed everything. It meant these colonies didn't just survive; they thrived through trade.

- Wheat.

- Barley.

- Oats.

- Rye.

These were the staples. On a middle colonies map, you can practically visualize the flow of flour from the inland mills down to the docks. This created a middle class of merchants and millers that didn't really exist in the same way elsewhere. In the South, you had wealthy plantation owners and poor laborers. In the middle, you had a bustling "middling sort."

Honestly, it was the start of the American dream.

The lack of a single dominant religion or ethnic group meant that people had to learn to get along to make a profit. It wasn't always peaceful. There were riots, land disputes, and horrific instances of frontier violence, particularly as settlers pushed west into Indigenous lands.

The Disputed Borders of the Middle Colonies Map

Maps lie. Or, at least, they represent what people wanted to own, not necessarily what they actually controlled.

Take the border between Pennsylvania and Maryland. For decades, it was a total mess. The charters were poorly written, and both families—the Penns and the Calverts—claimed the same strip of land. It got so bad that people were getting arrested by rival sheriffs in the same town.

Eventually, they had to bring in two experts, Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon.

The Mason-Dixon line is famous now as the cultural divide between North and South, but originally, it was just a way to fix a messy middle colonies map. It was a high-tech solution to a colonial headache.

📖 Related: Executive desk with drawers: Why your home office setup is probably failing you

And then there’s Delaware.

If you look at a map, Delaware looks like a tiny nub on the side of Pennsylvania. For a long time, it actually was part of Pennsylvania, known as the "Lower Counties." They eventually broke away because they didn't want to be governed from Philadelphia. It’s a tiny detail on the map, but it shows how even within this "unified" region, people were fiercely protective of their local identity.

Iron, Timber, and the Industrial Spark

While the South was tied to the soil and New England was tied to the sea, the middle colonies were tied to the mountains.

The Appalachian range runs right through the western edge of the middle colonies map. This gave them access to huge deposits of iron ore and endless forests for charcoal. By the time the Revolution rolled around, Pennsylvania and New Jersey were the industrial engines of the colonies.

Long before the Industrial Revolution really kicked off, the "iron plantations" of the middle colonies were churning out pots, pans, and—critically—long rifles.

You’ve got to realize how unique this was.

You had a region that could feed itself, trade with the world, and manufacture its own tools. It was self-sufficient in a way that the other colonies weren't. This economic power gave the middle colonies a massive amount of leverage during the Continental Congresses.

The Social Fabric of the Map

It wasn't all just dirt and trade. The middle colonies map was a map of ideas.

Because there was no "official" church, the region became a haven for radical thinkers. This is where Benjamin Franklin flourished. He was a Boston transplant who realized that the middle colonies were the only place where someone with his brain and his lack of pedigree could actually become a superstar.

The diversity wasn't just a fun fact; it was a survival strategy.

When you have Mennonites, Lutherans, Quakers, and Catholics all living in the same county, you can't have a theocracy. You have to have a secular government. You have to have pluralism. This is why so many of the foundational ideas of the U.S. Constitution—freedom of the press, freedom of religion—actually started in the middle colonies.

👉 See also: Monroe Central High School Ohio: What Local Families Actually Need to Know

How to Read a Middle Colonies Map Like a Historian

If you’re looking at one for a project or just out of curiosity, stop looking at the state lines. Instead, look at the "Fall Line."

The Fall Line is the point where the rivers stop being navigable for large ships because of waterfalls or rapids. On any middle colonies map, this line dictated where the major cities were built. Trenton, Philadelphia, and Wilmington are all roughly on this line.

It’s where the tide meets the rock.

Once you see that, you see why the population settled where it did. You see why the "backcountry" was so culturally different from the "tidewater" regions. The people living above the Fall Line were often the newer immigrants—the Germans and Scots-Irish—who were forced further inland.

This created a tension that defined colonial politics.

The wealthy merchants in the east wanted peace and trade. The settlers in the west wanted protection from raids and more land. This internal map of conflict is what eventually pushed Pennsylvania to become one of the most radical states during the American Revolution.

Actionable Insights for Your Map Study

If you’re trying to master this topic, don't just memorize the four states. Do this instead:

- Trace the Fall Line: Find a topographical map and overlay it with a middle colonies map. You’ll see exactly why cities popped up where they did.

- Follow the Flour: Look at the trade routes from Lancaster, PA, to Philadelphia. It explains the entire economy of the 18th century.

- Check the Ethnic Pockets: Research where the "German Coast" of Pennsylvania was compared to the Dutch influence in the Hudson Valley. The map will start to look like a patchwork quilt rather than a solid block.

- Analyze the River Basins: Understand that the Delaware River wasn't just a border; it was a shared resource that linked three of the four colonies together into a single economic unit.

The middle colonies weren't just a "middle" ground. They were the center of gravity. They took the best parts of the North and the South—the industry and the agriculture—and mixed them with a level of social tolerance that the world hadn't seen yet. When you look at that map, you’re looking at the birth of the American identity.

Keep exploring the nuances of the river valleys. The geography explains the politics every single time.

Next Steps for Deep Research:

- Compare a 1750 map of the region with a 2026 satellite view to see how the original river settlements evolved into the "Northeast Corridor" megalopolis.

- Examine the "Walking Purchase" of 1737 to see how map-making was used as a tool for land theft against the Lenape people.