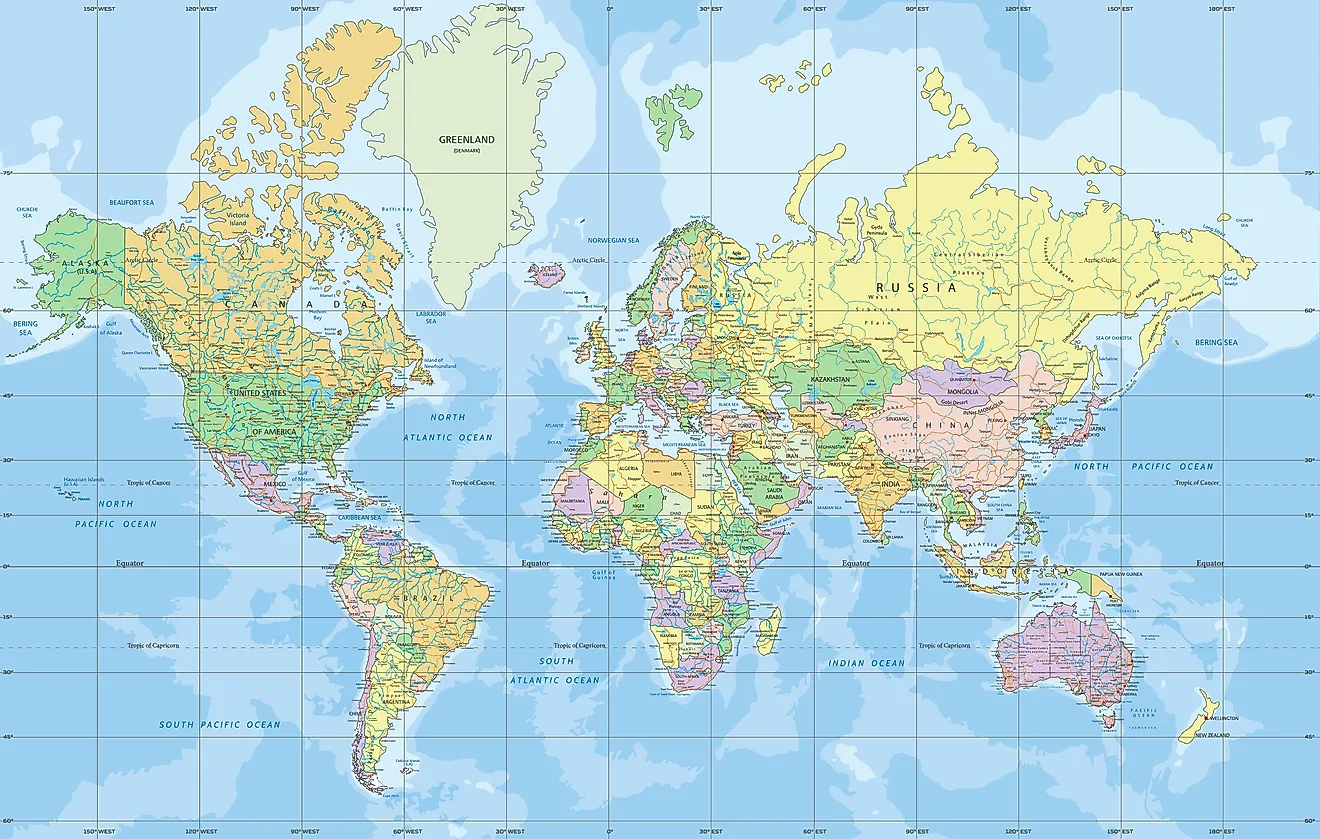

You’ve seen it a thousand times. It's hanging in every elementary school classroom, plastered across Google Maps, and likely folded up in your glovebox if you’re still a fan of paper. It’s the Mercator projection world map. We’ve used it for centuries to get from point A to point B without ending up in the middle of the Atlantic. But honestly? It’s kind of a mess.

If you look at a standard Mercator map, Greenland looks like a massive, icy continent roughly the size of Africa. It’s imposing. It’s huge. But in reality, Africa is about fourteen times larger than Greenland. You could fit the United States, China, India, and most of Europe inside Africa’s borders, and you’d still have room for a few extra countries. The Mercator map doesn't care about that. It’s not trying to show you how big things are; it’s trying to show you how to sail a ship.

Gerardus Mercator, a Flemish cartographer, dropped this map back in 1569. Back then, sailors weren't worried about the relative landmass of Brazil versus Scandinavia. They were worried about dying at sea. They needed a map where a straight line on the paper corresponded to a constant compass bearing. Mercator figured out a mathematical way to wrap the Earth’s sphere onto a cylinder. It worked. It changed the world. But it also distorted our entire perception of what the planet actually looks like.

The Math Behind the Distortion

The problem is fundamentally geometric. You can't flatten a sphere onto a plane without stretching something. Think about peeling an orange. If you try to lay the peel flat on a table, it tears or wrinkles. To make it a perfect rectangle, you have to stretch the top and bottom.

On a Mercator projection world map, the distortion increases as you move away from the equator. Near the 0° latitude line, things are pretty accurate. But as you head toward the poles, the map stretches vertically and horizontally at the same rate. This preserves shapes (conformal mapping) but wreaks havoc on size. This is why Antarctica looks like an infinite white abyss at the bottom of your screen, when it's actually the fifth-largest continent.

Why Google Maps (Still) Uses It

You’d think in 2026, with all our satellite data and AI, we’d have moved on to something more "honest." But Web Mercator—a slightly tweaked version of the original—is the industry standard for digital mapping.

Why? Because of local accuracy.

When you’re zooming into a street level in downtown Chicago, you want the intersections to look like 90-degree angles if they are actually 90-degree angles. If Google used an equal-area projection like the Gall-Peters, the streets would look skewed and tilted the further north you went. For a global view, it’s misleading. For finding a Starbucks three blocks away, it’s perfect. It keeps the "rhumb lines" straight, which is basically a fancy way of saying it keeps the world looking square when you’re zoomed in close.

📖 Related: The Richter Earthquake Magnitude Scale: Why We Still Use It Even Though It’s Technically Outdated

The Gall-Peters Controversy and the Social Impact

In the 1970s, a historian named Arno Peters started making a lot of noise. He claimed the Mercator projection world map was a tool of "cartographic imperialism." His argument was that by making northern, developed nations (Europe, North America, Russia) look massive while shrinking equatorial regions (Africa, South America, Southeast Asia), the map subconsciously reinforced a sense of colonial superiority.

He promoted the Gall-Peters projection instead.

This map is an "equal-area" projection. Africa looks like a long, stretching teardrop, and Europe looks tiny. It’s jarring to look at because the shapes are distorted, even if the sizes are correct. While Peters was right about the size bias, cartographers mostly rolled their eyes at his "new" discovery, since James Gall had actually created the projection decades earlier in 1855. It wasn't a conspiracy; it was just a different set of trade-offs.

Still, the debate hit a nerve. Boston Public Schools actually ditched Mercator for Gall-Peters in 2017 to give students a more "equitable" view of the world. It’s a classic example of how a simple tool for navigation can become a political lightning rod.

Other Maps You Should Probably Know About

If Mercator is for sailing and Gall-Peters is for fairness, what’s the "best" map?

There isn't one.

- The Robinson Projection: This was the National Geographic standard for a long time. It doesn't try to be perfect at anything. It distorts shape, area, and distance just a little bit everywhere to make the whole thing look "right" to the human eye.

- The Winkel Tripel: This replaced the Robinson at NatGeo in 1998. It’s a compromise projection that minimizes three types of distortion: area, direction, and distance. It’s arguably the most visually "accurate" flat map we have, though it’s useless for navigation because the lines of longitude are curved.

- The Dymaxion Map: Created by Buckminster Fuller, this looks like a folded-up piece of origami. It shows the Earth as one continuous landmass in a giant ocean. It has almost no distortion of shape or size, but it’s nearly impossible to use for traditional directions.

- AuthaGraph: This Japanese design is probably the most mathematically accurate flat map in existence. It maps the 3D sphere onto a 2D plane by dividing the world into 96 triangles. It's weird. It's beautiful. It shows the world as it really is, but you’ll have a hard time finding the North Pole on it.

The Mercator Legacy in the Age of Satellites

We don't really need the Mercator projection world map to navigate anymore. We have GPS. Your phone isn't calculating rhumb lines on a paper chart; it’s using trilateration from a constellation of satellites.

Yet, Mercator persists because of its utility in the browser. It allows for seamless panning and zooming. If you used a globe-based projection for a web map, the map would have to "re-project" every time you moved your finger, which would be a laggy nightmare.

We’ve basically traded geographic truth for user experience.

✨ Don't miss: What Does Mirrored Mean? Why Your Tech and Brain Are Doing the Same Thing

Actionable Insights for Using World Maps

If you're using a map for anything beyond finding the nearest pizza place, keep these points in mind so you don't get fooled by the 16th-century math:

- Check the Scale: If you’re looking at a Mercator map, remember that the scale bar at the bottom only applies to the latitude it’s sitting on. The "inch" at the equator represents much more distance than the "inch" at the top of the map.

- Use https://www.google.com/search?q=TrueSize.com: This is a great interactive tool where you can drag countries around a Mercator map and watch them shrink or grow. Dragging the UK over the equator or moving Indonesia up to Europe is a massive eye-opener.

- Swap Your Perspective: Try looking at a "South-Up" map or a Dymaxion map once in a while. It breaks the "North is Up" bias and forces your brain to see the planet as a floating rock rather than a static piece of paper.

- Context Matters: Use Mercator for local street directions. Use Winkel Tripel or Robinson for looking at global climate patterns or population density. Use Gall-Peters if you specifically want to compare the actual physical footprint of two nations.

The Mercator projection world map isn't "wrong." It’s just a tool designed for a specific job that it still does better than almost anything else. The mistake isn't in the map itself, but in our tendency to forget that the map is not the territory. It’s an abstraction. A very useful, very distorted, and very famous abstraction. Overcoming that distortion starts with simply realizing that Greenland isn't actually trying to swallow the rest of the world. It's just drawn that way.