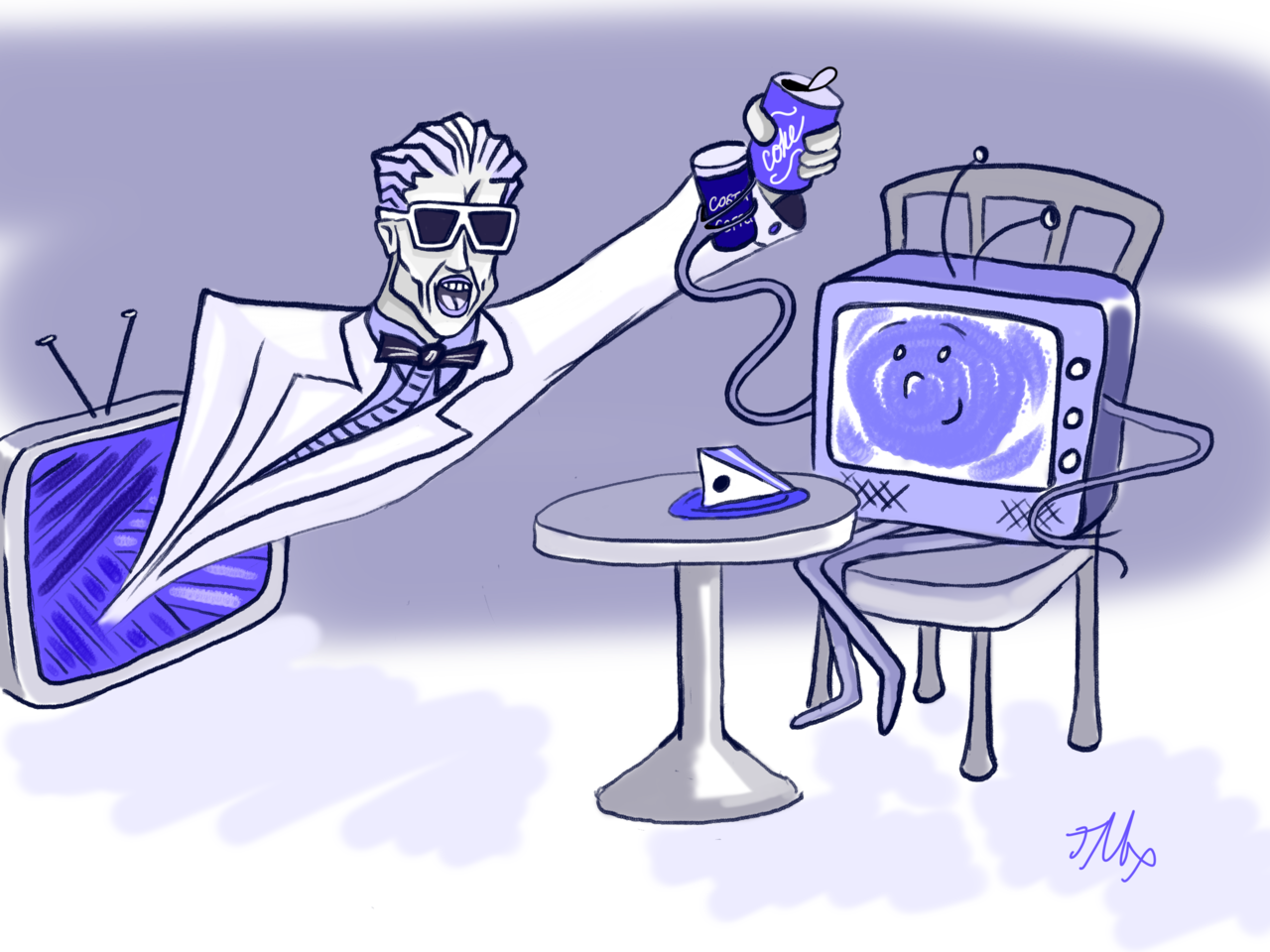

On a chilly Sunday night in November 1987, sports fans in Chicago were just trying to catch the highlights. It was 9:14 PM. Dan Roan, a veteran sports anchor for WGN-TV, was mid-sentence during the "Nine O'Clock News" when the screen suddenly flickered into an abyss of blackness. For about thirty seconds, a man wearing a rubbery, grinning Max Headroom mask—the iconic 80s "cyberpunk" pitchman—bounced erratically against a vibrating sheet of corrugated metal. There was no audio. Just a buzzing, rhythmic drone that felt like a digital migraine.

Then it stopped.

Roan, looking genuinely bewildered, laughed it off on air. "If you're wondering what happened, so am I," he told the viewers. But the hackers weren't done. Two hours later, during a broadcast of Doctor Who on the PBS affiliate WTTW, the mask returned. This time, there was audio. Distorted, screeching audio. The figure mocked WGN pundit Chuck Swirsky, hummed the theme to Clutch Cargo, and ended the transmission by getting spanked with a flyswatter by an accomplice in a French maid outfit.

It was weird. It was brazen. And nearly forty years later, nobody knows who did it.

How the Max Headroom Signal Intrusion Actually Happened

Most people assume hacking a TV station requires a room full of supercomputers. In 1987, it just required a high-gain antenna and a very well-placed van. This wasn't a "software" hack. It was an act of raw physical radio frequency (RF) dominance.

The technical term for this is broadcast signal intrusion. To understand why it worked, you have to look at how TV stations got their video to the transmitter. Back then, WGN used a Studio-to-Transmitter Link (STL). They’d beam a microwave signal from their studio on Bradley Place directly to a receiver atop the John Hancock Center. The hackers simply parked themselves somewhere in the line of sight and blasted a more powerful signal on the same frequency.

📖 Related: How to actually make Genius Bar appointment sessions happen without the headache

Imagine two people shouting. If the first person is a mile away and the second person is standing right next to you with a megaphone, you’re only going to hear the megaphone. That’s essentially what happened. The WGN engineers at the Hancock Center were helpless; their equipment just "locked on" to the strongest signal it could find.

By the time the WTTW intrusion happened later that night, the hackers had refined their setup. WTTW didn't have engineers on duty at the transmitter site to manually switch frequencies, which is why the second hijack lasted over 90 seconds. It only ended because the pranksters decided they were finished.

The Investigation That Hit a Brick Wall

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) didn't find it funny. Neither did the FBI. Signal hijacking is a felony, and the authorities were terrified that if someone could interrupt the news to show a guy in a mask, they could also interrupt it to broadcast false emergency alerts or political propaganda.

Investigators fanned out across Chicago. They looked for people with specialized knowledge of microwave equipment. They checked the "Max Headroom" mask sales at local costume shops. They even analyzed the corrugated metal backdrop, thinking it might be a specific type of industrial siding found in a local warehouse.

Nothing.

👉 See also: IG Story No Account: How to View Instagram Stories Privately Without Logging In

The audio was the biggest hurdle. Because it was so heavily distorted and recorded on primitive equipment, voice stress analysis and other forensic tools of the era were basically useless. There were theories, of course. Some pointed to the underground "phreaker" culture—early hackers who obsessed over telecommunications. Others thought it might be a disgruntled ex-employee of a local TV station who knew the exact frequencies and locations of the STL links.

Even today, Reddit sleuths and amateur investigators point fingers at specific individuals in the Chicago tech scene of the late 80s. One popular theory involving two brothers with a penchant for avant-garde video art made waves a few years ago, but it was never proven. The statute of limitations has long since expired, yet the perpetrators remain silent. Honestly, the mystery is probably the only reason we still talk about it. If it had been a couple of bored college kids who got caught a week later, it would be a footnote in a textbook. Instead, it’s a legend.

Why We Can't (Easily) Do This Anymore

You might wonder why we don't see this happening today during the Super Bowl or the Oscars. The transition from analog to digital television changed the game entirely.

In the analog days, you just had to be louder than the original signal. In the digital age, signals are encrypted and compressed. If you try to "overlay" a digital signal today, the receiver usually just sees a pile of corrupted data and displays a black screen or an error message. It doesn't gracefully transition into your pirate broadcast.

Furthermore, modern STLs are often fiber-optic or highly encrypted digital microwave links. You can't just point a dish at a skyscraper and hope for the best. The barrier to entry moved from "owning a powerful antenna" to "possessing high-level cryptographic keys and network access."

✨ Don't miss: How Big is 70 Inches? What Most People Get Wrong Before Buying

The Cultural Shadow of the "Headroom" Incident

There is something uniquely unsettling about the footage. The low-res grain. The jerky movement. The way the mask’s jaw doesn't move when the voice speaks. It taps into "uncanny valley" territory. Max Headroom himself was already a weird character—a fictional AI played by actor Matt Freely, designed to look like a glitchy computer program. Using that specific face to hijack a real-world signal was a meta-commentary that felt like the future had arrived in the creepiest way possible.

It also highlighted the vulnerability of our information systems. We trust that when we turn on the TV, the people on the screen are who they say they are. The Max Headroom signal intrusion shattered that illusion for a few minutes. It proved that the "official" voice of the media could be silenced by anyone with enough technical know-how and a sense of mischief.

Lessons and Takeaways for the Modern Era

While the specific method used in 1987 is largely obsolete, the spirit of the Max Headroom intrusion lives on in modern cybersecurity. It was one of the first high-profile examples of "social engineering" through technology—using a recognizable pop-culture icon to create confusion and grab attention.

If you’re interested in the history of broadcast security or the evolution of hacking, there are a few things you should actually do to dive deeper:

- Watch the original WTTW footage: Pay close attention to the background and the audio. You’ll notice the hackers were likely in a small, cramped space—possibly the back of a van, which explains the "swaying" motion of the backdrop.

- Research the "Captain Midnight" incident: Occurring just a year before the Chicago hack, this involved a man named John R. MacDougall who hijacked a Home Box Office (HBO) satellite signal to protest high prices. Unlike the Max Headroom hackers, he was caught because he left a paper trail.

- Explore SDR (Software Defined Radio): If you want to understand how frequencies work today, getting a cheap RTL-SDR dongle allows you to see how the airwaves are crowded with signals. It’s a legal way to see the "invisible" world the 1987 hackers exploited.

- Read the FCC reports: Most of the primary documents from the 1987 investigation are available through FOIA requests or online archives. They reveal just how panicked the government was about the potential for "electronic terrorism."

The Max Headroom signal intrusion remains the ultimate "cold case" of the digital age. It was a prank that turned into a myth, a brief moment where the mask of professional broadcasting slipped and showed us something chaotic underneath. It reminds us that no matter how secure we think our networks are, there’s always someone out there looking for a way to break in—just for the hell of it.