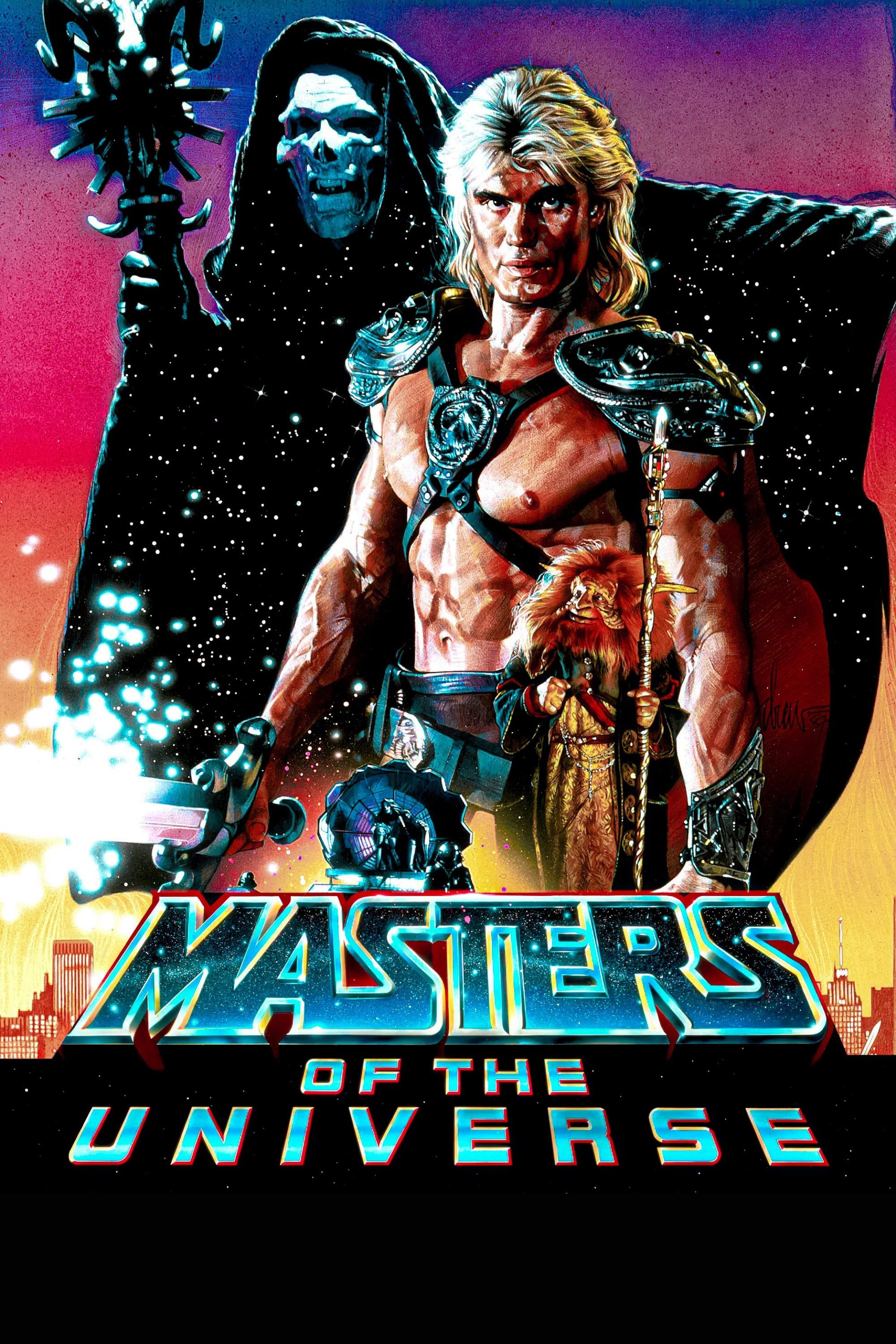

He-Man didn't belong on Earth. Not really. But back in the late eighties, Cannon Films was bleeding cash and desperation has a funny way of birthing cult classics. If you grew up with a plastic Power Sword in your hand, the Masters of the Universe 1987 live-action film probably felt like a fever dream. It wasn't the bright, colorful Eternia we saw in the Filmation cartoons. It was grimy. It was dark. It was basically "Star Wars" meets a suburban car wash.

People hated it then. Critics absolutely tore it to shreds. They called it a cheap knock-off, a cynical cash-in on a toy line that was already starting to lose its grip on the cultural zeitgeist. But here's the thing: they were wrong. Or, at the very least, they were looking at it through the wrong lens. Looking back now, with the benefit of decades of cinematic context, the movie is a fascinating artifact of practical effects and Shakespearean ambition trapped inside a B-movie budget.

The Cannon Films Gamble

You can't talk about this movie without talking about Golan-Globus. Cannon Films was the wild west of Hollywood. They were the ones churning out Death Wish sequels and Chuck Norris vehicles. When they landed the rights to Mattel’s crown jewel, they didn't have the $100 million a project like this actually required. They had about $22 million, which, even in 1987, was tight for an intergalactic epic.

Director Gary Goddard was handed a monumental task. He had to bring He-Man to life without the budget for a sprawling, alien world. The solution? Bring the war to Earth. It’s a classic trope used to save money on set construction, but in the context of the Masters of the Universe 1987 production, it created this weird, liminal space where high fantasy collided with the neon-soaked reality of the 80s.

Frank Langella Saved Everything

Let’s be real. Dolph Lundgren looked the part. He was a literal god carved out of granite. His accent was a bit thick, and his acting was, well, "physical," but he held the sword with authority. But the reason we are still talking about this movie in 2026 isn't Dolph. It’s Frank Langella.

👉 See also: Questions From Black Card Revoked: The Culture Test That Might Just Get You Roasted

Langella didn't treat this like a toy commercial. He treated it like Richard III. He famously took the role because his son loved the toys, but he stayed for the scenery-chewing. Beneath pounds of heavy prosthetic makeup, Langella delivered a performance that is legitimately terrifying and oddly poetic. Most villains in 80s kids' movies were bumbling idiots. His Skeletor was a nihilist. When he stands in the throne room and whispers about becoming a god, you actually believe he might do it. He didn't just want to beat He-Man; he wanted to unmake the universe.

The makeup work by William Stout and the legendary Michael Westmore shouldn't be overlooked either. They moved away from the blue-skinned bodybuilder look of the cartoon and toward something more skeletal and regal. It was a pivot toward "Dark Fantasy," a genre that was thriving with films like Legend and Labyrinth.

The Moebius Influence

If the movie looks "off" to you compared to the toys, there's a reason for that. Production designer William Stout was heavily influenced by the French artist Jean "Moebius" Giraud. This is why the aesthetic feels more like a heavy metal comic book than a Saturday morning cartoon. The shock troopers didn't look like the plastic toys; they looked like cybernetic samurai. The Air Centurions—those flying soldiers that terrified kids—were a stroke of design genius.

They used a lot of matte paintings. Huge, sweeping vistas of the wasted lands of Eternia were hand-painted on glass. In an era before CGI dominated everything, these paintings provided a scale that the physical sets couldn't match.

✨ Don't miss: The Reality of Sex Movies From Africa: Censorship, Nollywood, and the Digital Underground

What Most People Get Wrong About the Plot

The common complaint is that the movie spends too much time on Earth with "the kids." Courtney Cox (pre-Friends) and Robert Duncan McNeill (pre-Star Trek: Voyager) play the teenagers who find the Cosmic Key. Yes, it’s a bit of a "E.T." rip-off. Yes, the scenes in the junkyard and the fried chicken shop feel small.

But look at the stakes. The Masters of the Universe 1987 film introduced the Cosmic Key—a device that could open portals anywhere through music. This wasn't just a MacGuffin. It was a clever way to bridge the gap between science fiction and fantasy. The creator of the key, Gwildor, was a replacement for Orko because Orko was technically impossible to film on their budget. Gwildor, played by Billy Barty, brings a weird, whimsical soul to the film that balances out the grimness of the villains.

Why It Failed (And Why It Lived)

The movie came out in August 1987. By then, the He-Man craze was cooling. Kids were moving on to the Transformers and the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. The toy line was struggling. Mattel was actually in the process of scaling back.

When the movie didn't become a Star Wars-level hit, Cannon Films collapsed shortly after. They had already started pre-production on a sequel. They had the sets built and the costumes ready. When the money dried up, they took those sets and that script, tweaked it, and turned it into the Jean-Claude Van Damme movie Cyborg. It's a bizarre footnote in cinema history. One movie's failure birthed a different action star's career.

🔗 Read more: Alfonso Cuarón: Why the Harry Potter 3 Director Changed the Wizarding World Forever

But the "failure" label is misleading. On home video, the movie became a titan. It lived on in the hearts of kids who appreciated the darker tone. It was a gateway drug to more mature fantasy.

The Practical Effects Masterclass

We live in a world of flat, digital lighting. The Masters of the Universe 1987 movie is the opposite. It is drenched in practical lighting effects. Sparklers, pyrotechnics, real smoke, and heavy animatronics. When Blade and Saurod—the movie-exclusive villains—hit the screen, they have a tactile weight. You can hear the clinking of their armor.

The final battle between He-Man and "God-Skeletor" (when Skeletor turns gold) is a psychedelic trip. It's all gold leaf and shimmering lights. It shouldn't work. It should look tacky. Instead, it looks like an old religious painting come to life.

Actionable Insights for Fans and Collectors

If you’re looking to revisit this era or understand its impact, don't just watch the movie. Look at the ripple effects it had on the franchise.

- Track down the "Movie Series" Figures: Mattel eventually released toys based on the film's designs. The Skeletor and God-Skeletor figures from the Masters of the Universe Classics line are highly sought after because they capture that Frank Langella menace.

- Study the Soundtrack: Bill Conti, who did the music for Rocky, composed the score. It is sweeping, brass-heavy, and honestly better than the movie probably deserved. Listen to it as a standalone piece of orchestral work.

- Check out the "Power of Grayskull" Documentary: There are deep dives into the production woes of Cannon Films that make you realize it's a miracle this movie was even finished.

- Look for the Easter Eggs: In the final post-credits scene (one of the first in cinema history!), Skeletor's head pops out of the water and he says, "I'll be back!" It's a haunting promise that we never got to see fulfilled.

The Masters of the Universe 1987 isn't a perfect movie. It's messy. It's weird. It's a product of a studio that was burning down while the cameras were rolling. But it has more heart and visual imagination than half of the $200 million blockbusters we see today. It dared to be different. It dared to make He-Man a bit more "adult." For that alone, it deserves a spot in the sci-fi hall of fame.

If you haven't seen it in a decade, go back. Ignore the cheesy Earth dialogue. Focus on the production design. Look at the way Langella moves. You'll see a film that was trying to be something much bigger than a toy commercial. It was trying to be a legend.