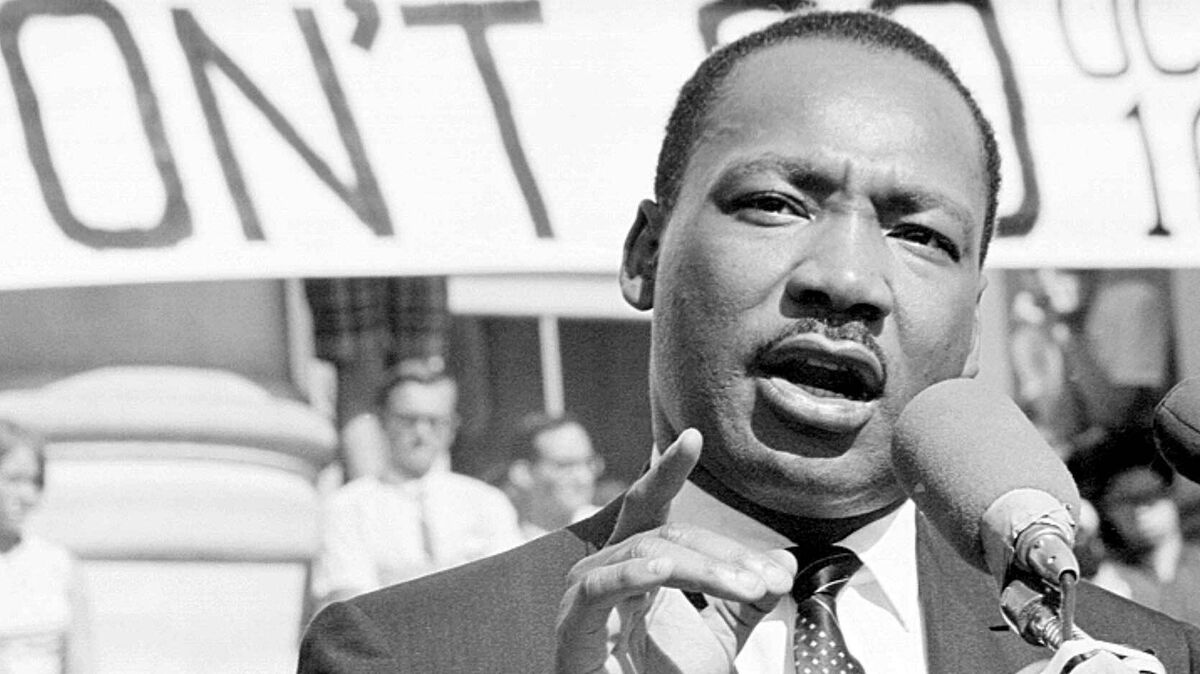

History isn't just a bunch of dusty dates in a textbook. Honestly, if you look at the Martin Luther King civil rights movement, it’s more like a blueprint for how people actually change the world when the odds are stacked against them. People think they know the story. They think it’s just a guy with a dream standing in front of a giant marble statue in D.C., but it was way messier than that. It was dangerous. It was calculated.

Dr. King wasn’t just a dreamer; he was a master strategist.

Think about it. In the 1950s and 60s, the United States was a place where, depending on your skin color, you couldn't eat at certain counters or even use the same bathroom as someone else. It sounds surreal now, but it was the law. King didn't just show up and give a speech to fix it. He and a massive network of activists—people like Bayard Rustin, Ella Baker, and Ralph Abernathy—had to figure out how to break a system that was designed to stay broken.

The Strategy Behind the Struggle

Most folks forget that the Martin Luther King civil rights movement was basically an exercise in high-stakes psychology. King leaned heavily into nonviolent resistance. That wasn't just because he was a man of the cloth; it was because he knew how it would look on the evening news.

Imagine sitting in your living room in 1963. You turn on the TV and see students in their Sunday best being sprayed with high-pressure fire hoses. You see police dogs lunging at teenagers. Then you see the protesters just standing there. They aren't fighting back. That contrast? That was the point.

- It stripped away the moral high ground of the oppressors.

- It forced the federal government to look like the "bad guy" if they didn't intervene.

- It made the average person in Ohio or Oregon realize that "peaceful" segregation was a lie.

King was influenced by Gandhi, sure, but he also had to navigate the specific, brutal reality of the American South. The Montgomery Bus Boycott wasn't just a one-day thing. It lasted 381 days. People walked to work in the rain for over a year. They carpooled. They wore out their shoes. It was an economic siege. This wasn't just about "feelings"; it was about hitting the city where it hurt: the wallet.

What People Get Wrong About the "I Have a Dream" Speech

We’ve all heard the snippets. It’s the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. (Note the "Jobs" part—people usually leave that out). But here is a weird fact: King almost didn't say the "I have a dream" part.

He had a prepared script. It was a bit more formal. Mahalia Jackson, the legendary gospel singer, was standing nearby and shouted, "Tell 'em about the dream, Martin!" He pivoted. He went off-script. The most famous speech in American history was, in its most iconic moments, an improvisation.

But let’s be real. If you only focus on the dream, you miss the bite. In that same speech, King talked about the "promissory note" that America had defaulted on. He said the nation had given Black citizens a "bad check" marked "insufficient funds." He was talking about systemic inequality, not just a color-blind future where everyone holds hands.

The Birmingham Campaign and the Letter

If you want to understand the grit of the Martin Luther King civil rights movement, you have to look at Birmingham, 1963. They called it "Bombingham" because it was so violent. King got thrown into a narrow, dark jail cell. While he was in there, he read a newspaper where local white clergymen called his actions "unwise and untimely."

He didn't have fancy stationery. He started writing his response on the margins of that newspaper and on scraps of toilet paper.

✨ Don't miss: How Many Amendments to the Constitution Are There? The Real Count and Why It’s Not Growing

That document, the Letter from Birmingham Jail, is arguably more important than the "Dream" speech. He basically told the "white moderate" that their preference for "order" over "justice" was a bigger hurdle than the KKK. He was calling out the people who said, "We agree with your goals, but not your methods." It was a blunt, intellectual slap in the face to anyone sitting on the sidelines.

Beyond the South: The Chicago Freedom Movement

A lot of people think the movement was just a "Southern thing." Nope.

In 1966, King moved into a dilapidated apartment in Chicago to highlight the terrible housing conditions in the North. He found out that the racism in the North wasn't necessarily in the laws (de jure), but it was definitely in the reality of how people lived (de facto). He faced some of the most violent mobs of his career in Chicago—not Alabama. He famously said that the crowds in Mississippi and Georgia had nothing on the "hate-filled" faces he saw in Illinois.

The Radical King vs. The Sanitized King

By the time he was assassinated in 1968, Dr. King was actually pretty unpopular. We love him now, but back then, his approval rating was tanking. Why? Because he started talking about things that made the establishment even more nervous than desegregation did.

- The Vietnam War: He came out swinging against it in his Beyond Vietnam speech at Riverside Church. He called the U.S. the "greatest purveyor of violence in the world today." That lost him his alliance with President Lyndon B. Johnson.

- The Poor People's Campaign: He started focusing on class. He wanted a "multiracial army of the poor" to march on Washington and demand a guaranteed income and better housing.

- Global Human Rights: He was looking at the bigger picture, connecting the struggle in the U.S. to anti-colonial movements in Africa and South America.

He was becoming a revolutionary, not just a reformer. When we talk about the Martin Luther King civil rights movement, we often stop at the 1965 Voting Rights Act. But King didn't stop there. He was pushing for a "radical redistribution of economic and political power."

✨ Don't miss: Missouri Archaeologists Amazon Geoglyphs: What Most People Get Wrong

Why This Matters in 2026

History repeats itself, but it also rhymes. Today, we still see debates about voting access, police reform, and economic gaps that look suspiciously like the ones King was fighting.

The movement taught us that change doesn't happen because people are nice. It happens because people organize. It happens because of "creative tension." King's brilliance was in making it impossible for the average person to look away from the injustice happening right in front of them.

If you’re looking to apply these lessons today, start with the "Small Wins" strategy. The Montgomery Boycott started with one woman—Rosa Parks—and one specific bus line. It wasn't about fixing the whole world on Monday morning. It was about one focused, tactical strike that grew into a landslide.

Moving Forward: Actionable Steps

Learning about the Martin Luther King civil rights movement shouldn't just be an academic exercise. It’s a set of tools you can use if you care about your community.

First, look at local legislation. King knew that federal laws like the Civil Rights Act of 1964 were the goal, but the pressure started at the municipal level. If you want to see change, start at city council meetings.

Second, understand the power of the "Economic Withdrawal." The movement used boycotts to force change. In today’s world, where you spend your money is probably your loudest political voice. Support businesses that align with your values and pull back from those that don't.

Third, get comfortable with being "uncomfortable." King’s whole philosophy was about creating a crisis that forced a negotiation. If you’re trying to change something at work or in your neighborhood, realize that polite requests often get ignored. You have to find a way to make the status quo more "expensive" or "painful" than the change you're asking for.

The legacy of Dr. King isn't found in a holiday or a street name. It's found in the realization that a group of determined people, armed with a clear plan and a whole lot of courage, can actually bend the arc of the moral universe toward justice. It just takes a lot more work than most people realize.

Check the Primary Sources

👉 See also: Is CBS News Liberal or Conservative? What Most People Get Wrong

To really get the full picture, don't just take a summary's word for it. Dig into these specific documents:

- Letter from Birmingham Jail (1963)

- The Drum Major Instinct sermon (1968)

- Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community? (King’s final book)

These texts show a man who was deeply worried about the future of the country but remained stubbornly hopeful that "we shall overcome." That hope wasn't a feeling—it was a tactic.