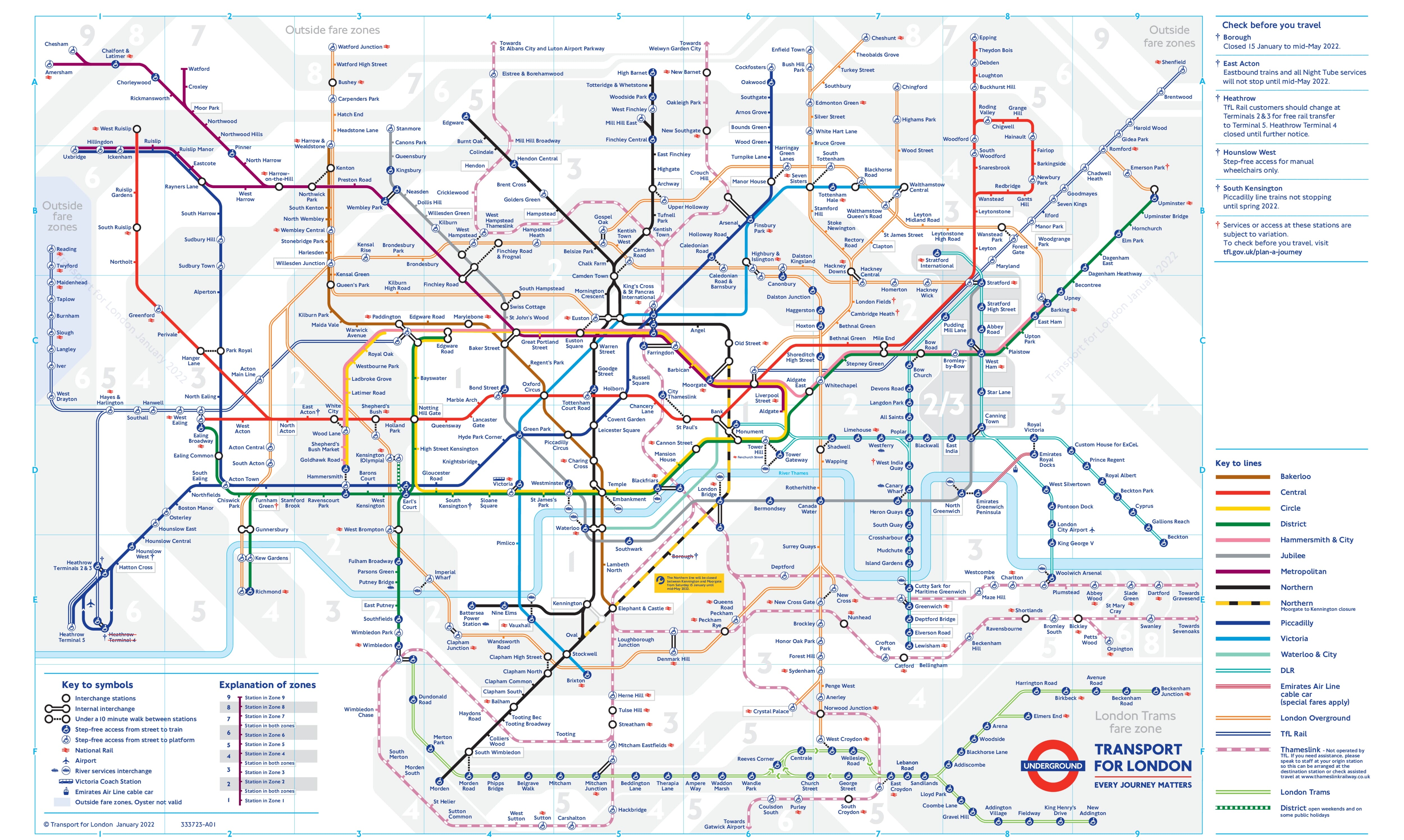

You're standing at South Kensington. You look at that iconic grid of colored lines, the map underground London tube travelers have relied on for decades, and you think you know exactly where you are. You don't. That’s the beauty of it, honestly. The map is a lie, but it’s a brilliant one that basically saved the city from a nervous breakdown in the 1930s.

It's weird.

We trust this diagram more than we trust our own eyes when we step out of a station. If the map says two stations are far apart, we stay on the train. If it says they're close, we walk. But the reality of London’s geography is a messy, tangled knot that looks nothing like the clean 45-degree angles Harry Beck dreamt up back in 1931.

The Genius Who Was Paid Almost Nothing

Harry Beck was a technical draftsman. He was out of a job and bored. At the time, the London Underground maps were geographical nightmares. They tried to show the actual distance between stations, which meant the center of the map was a crowded, illegible ink-blot of text, while the edges were mostly empty space. It was ugly. It was confusing. People hated it.

Beck had a "lightbulb" moment that changed graphic design forever. He realized that when you’re underground, you don’t care about what’s happening on the surface. You don’t care if you’re passing under a park or a graveyard. You just want to know where to change trains. He treated the map underground London tube system like an electrical circuit.

He submitted his design in 1931. The UERL (Underground Electric Railways Company of London) actually rejected it at first. They thought it was "too revolutionary." Imagine that. They eventually gave it a trial run of 500 copies in 1932, and the public went absolutely wild for it. Beck was paid a measly ten guineas for the design. That’s about £600 in today’s money for creating the most influential piece of information design in human history. Talk about a bad deal.

Why Your Eyes Are Lying To You

If you look at the map right now, look at Lancaster Gate and Paddington. They look like they're a fair distance apart, right? You’d take the Central line and change at Notting Hill Gate for the District. Wrong. It’s a five-minute walk. You can literally see one from the other if you stand in the right spot on the street.

🔗 Read more: Floating Lantern Festival 2025: What Most People Get Wrong

The map distorts space to create clarity. The "The Map Is Not The Territory" concept is never more true than in the London Underground. This distortion is why tourists end up spending £2.70 and fifteen minutes traveling between Leicester Square and Covent Garden—a distance of only 250 meters. It’s the shortest journey on the network. You can walk it in less time than it takes to get down the escalator.

Ken Garland, a legendary designer and author of Mr. Beck’s Underground Map, used to talk about how this design changed our mental "image" of London. Because the map is a schematic, we think of the city as a series of connected nodes rather than a physical landscape. The Elizabeth Line threw a massive wrench into this recently. Adding a high-speed, long-distance line to a map designed for slow, short hops made the diagram look "fat" and cluttered. Purists hate it. Commuters just want to get to Reading without crying.

The Secret Geometry of the Tube

There are rules to the map underground London tube layout that you probably notice subconsciously. All lines are either horizontal, vertical, or at a 45-degree angle. No exceptions. This is what makes it "readable."

But the map has had to evolve. When the Victoria Line was added in the 60s, the map had to stretch. When the Jubilee line extension arrived in 1999, it had to warp again. Nowadays, we have the "TfL Go" app and digital versions, but the paper map—the one you see on the platform—remains the gold standard.

Did you know there’s a secret version? Well, not secret, but "geographically accurate." If you look at the official TfL "Geographically Accurate" map, it looks like a bowl of colorful spaghetti that someone dropped on the floor. It’s terrifying. It shows just how much the standard map "cheats" to make the city feel manageable. The distance between stations in Zone 1 is blown up to massive proportions, while the long gaps between stations in Zone 6 are compressed. It's a psychological trick to keep us calm.

Mistakes, Ghost Stations, and Typos

Even experts get things wrong. Over the years, the map has featured various "ghosts."

💡 You might also like: Finding Your Way: What the Tenderloin San Francisco Map Actually Tells You

- North End (Bull & Bush): This station was never finished. It’s a deep-level bunker now. It never made the official public map, but it exists in the tunnels.

- The Thames: For a brief, dark period in 2009, the River Thames was removed from the map. People lost their minds. The river is the only geographical landmark on the map, and without it, Londoners felt untethered. It was put back within months.

- Morden: It looks like the end of the world on the map. In reality, it’s just a busy suburb in South London. The map makes it feel like you’re traveling to the moon.

The current map is struggling. We have the Overground (the "Ginger" line), the DLR, the Tramlink, and now the Elizabeth Line. The canvas is getting crowded. Some designers, like Max Roberts, argue that we should move toward a "curved" map design to handle the complexity. Others think we should stick to Beck’s rigid angles until the bitter end.

How to Actually Use the Map Without Being a Tourist

Most people just follow the lines. If you want to move through London like someone who actually lives here, you have to learn when to ignore the map underground London tube layout entirely.

First, look for the "interchange" blobs. Some of them are massive. At King's Cross St. Pancras, an "interchange" might involve a ten-minute walk underground. The map makes it look like a simple hop. It isn't.

Second, check the walking maps. TfL actually publishes maps that show how many steps it takes to walk between stations. This is the ultimate "anti-map." If the walk is under 1,000 steps, don't go underground. You’ll save money, see the sun (occasionally), and avoid the 30-degree heat of the Central Line in July.

Third, understand the "curves." The District and Circle lines are notoriously slow because they are "cut-and-cover" tunnels. They follow the paths of old roads. The deep-level lines (Northern, Central, Piccadilly) were bored through the clay. They’re faster, but they’re deeper. The map doesn't show depth, but your ears will tell you when you’re on a deep line—the screeching is a dead giveaway.

The Evolution of an Icon

We’ve seen iterations that include the "Emirates Air Line" (the cable car) which most Londoners find hilarious because it goes from nowhere to nowhere. We’ve seen "walking distance" versions and even versions where the station names are replaced by the names of famous footballers or scientists.

📖 Related: Finding Your Way: What the Map of Ventura California Actually Tells You

But the core remains. That blue, red, and yellow skeleton. It’s the DNA of the city.

The most fascinating part is that the map influenced almost every other transit system in the world. New York tried it (and failed, because New Yorkers are stubborn and wanted their geography back). Tokyo uses a version of it. Paris uses it. It’s a universal language of "how to get from A to B without panicking."

When you’re looking at the map underground London tube today, you’re looking at a piece of art that’s also a tool. It's a miracle of simplification. It takes a city of 9 million people and 250 miles of track and turns it into a tidy little postcard.

Actionable Steps for Your Next Trip

Stop relying on the colored lines as a literal representation of London. To truly master the system, do this:

- Download the "Geographically Accurate" PDF from the TfL website just to compare it with the standard one. It will blow your mind how much the distance is distorted.

- Look for the "Walking Distance" indicators. If you’re at Shepherd’s Bush (Central Line), the Overground station is right there, but the map makes them look like separate entities.

- Use the "Out-of-Station Interchange" (OSI) trick. Sometimes you have to tap out of one station and walk to another to change lines (like at Canary Wharf). The map shows a link, but it doesn't tell you that you’ll be walking through a shopping mall to find the other platform.

- Avoid the "Green" and "Yellow" lines during rush hour if you can help it. They share tracks and are prone to "signal failures" (the polite term for "the 150-year-old equipment is tired").

- Check the "Step-Free" map if you have luggage. The standard map is a nightmare for anyone with a suitcase. The little wheelchair symbols are your only friends.

London is a city built on top of itself. The map is just the top layer. Understanding that the map is a functional lie is the first step toward becoming a real Londoner. You don't need a compass; you just need to know that the distance between "Bank" and "Monument" is basically one very long hallway, no matter what the diagram tells you.

Next time you're stuck at a station, look at the bottom right corner of the map. You'll see the version number and the date. It changes constantly. It’s a living document. It’s the heartbeat of the city, even if it does make you walk half a mile in the wrong direction once in a while.