If you look at a map of West Germany from, say, 1975, it looks like a jigsaw puzzle with a missing piece right in the middle of its eastern neighbor. That missing piece was West Berlin. It sat there, a tiny island of democracy drowning in a sea of Soviet-controlled territory. It’s honestly one of the strangest geopolitical anomalies in modern history.

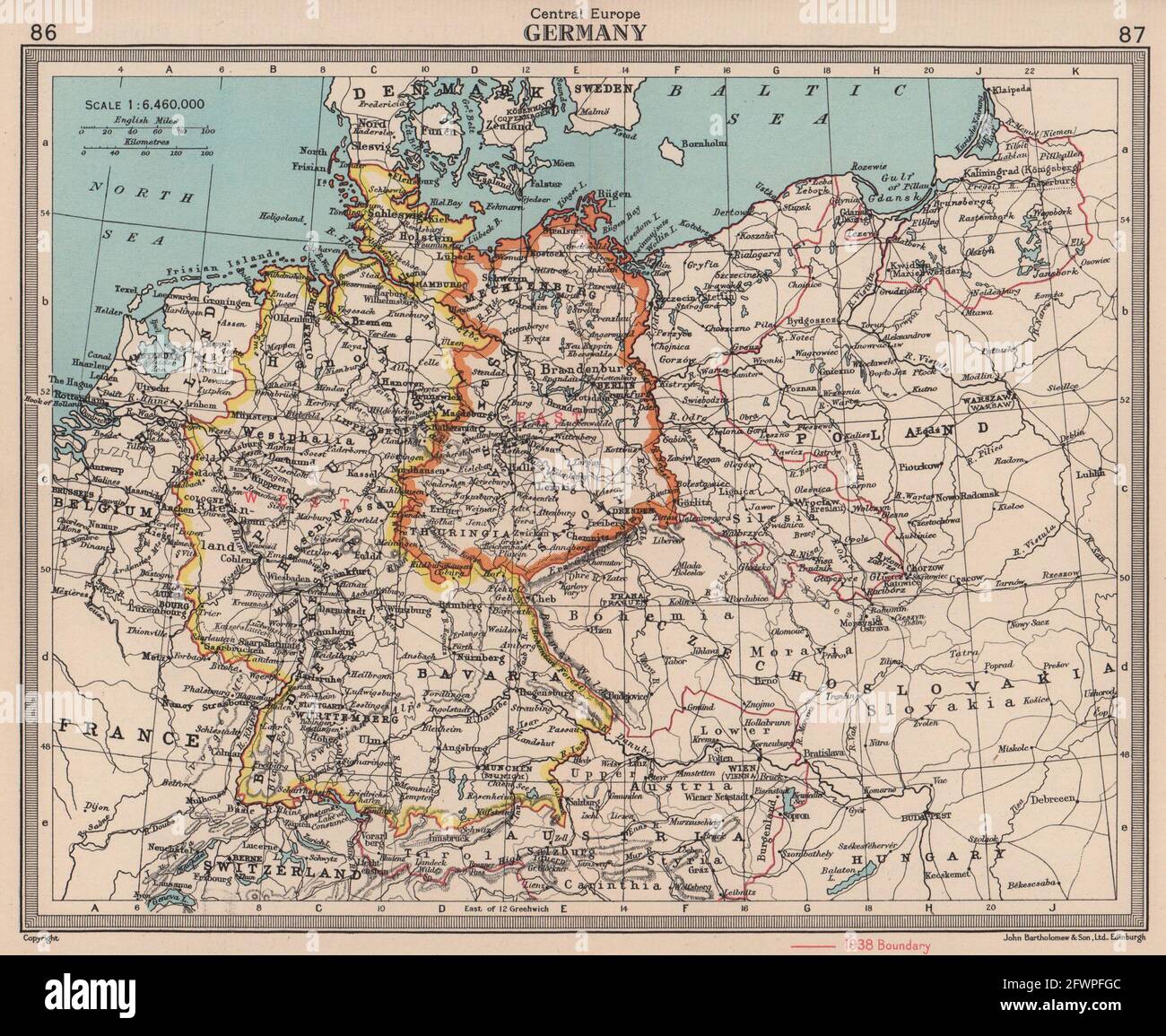

When people talk about the map of West Germany, they usually think of the "Federal Republic of Germany" (FRG). It wasn't just a country; it was a statement. From 1949 to 1990, this map defined the front lines of the Cold War. You had the Rhine River snaking through the industrial heartland in the west, the Bavarian Alps touching the sky in the south, and that tense, barbed-wire scar known as the Inner German Border running along the east.

The Border That Wasn't Supposed to Exist

The map of West Germany didn't happen because someone sat down and planned a new nation. It happened because the Allies couldn't agree on what to do with a defeated Third Reich. Basically, the British, French, and Americans mashed their occupation zones together. This created a T-shaped territory that stretched from the North Sea down to the Austrian border.

It's wild to think about how precarious those borders were. The "Green Border"—the line between East and West—wasn't just a line on a map. It was a 866-mile-long death strip. If you were standing in a village like Mödlareuth, the map literally cut your town in half. They called it "Little Berlin." One side had colorful West German storefronts and the other had gray walls and Kalashnikovs.

The Strange Case of the Enclaves

Most people forget that the map of West Germany was full of holes. Take Steinstücken. It was a tiny patch of West Berlin territory that sat entirely inside East Germany. For years, the people living there were basically hostages of geography. To get to work, they had to be escorted by military police through East German territory. Eventually, they built a tiny road—a paved umbilical cord—just to keep the map "functional."

🔗 Read more: Why an Escape Room Stroudsburg PA Trip is the Best Way to Test Your Friendships

Then you have the "Zonengrenze." This wasn't just a border; it was a psychological wall. If you lived in West German cities like Kassel or Wolfsburg, you were basically living at the edge of the world. The map ended abruptly. Roads that had existed for centuries just... stopped. They led into forests where the trees were eventually replaced by minefields and guard towers.

Bonn: The Capital Nobody Expected

On a map of West Germany, the capital wasn't Berlin. It was Bonn.

Bonn is a quiet, somewhat sleepy university city on the Rhine. Why there? Because Konrad Adenauer, the first Chancellor, liked it. Also, they didn't want a "real" capital. Choosing a major city like Frankfurt would have made the division of Germany feel permanent. By picking Bonn, they were essentially saying, "We’re just staying here until we can go back to Berlin."

The map of West Germany reflects this "temporary" mindset. The government buildings were modest. The geography of power was decentralized. Unlike France, where everything leads to Paris, the West German map was a web of powerful regional states—Länder. Munich, Hamburg, and Stuttgart all operated like mini-capitals. This decentralization is exactly why Germany’s economy is so robust today; the map forced them to spread the wealth.

💡 You might also like: Why San Luis Valley Colorado is the Weirdest, Most Beautiful Place You’ve Never Been

The Geography of the Economic Miracle

If you trace the industrial zones on a map of West Germany, you’re looking at the blueprint for the Wirtschaftswunder (Economic Miracle). The Ruhr area—cities like Essen and Dortmund—was the engine room.

But look further south. The map shows a massive shift toward Bavaria. Before the war, Bavaria was mostly known for beer and farming. After the division, many companies fled the Soviet zone and settled in Munich and Erlangen. Siemens is a classic example. They moved their headquarters from Berlin to Munich, forever changing the economic geography of the south.

- The Rhine-Main Area: Centered around Frankfurt, this became the financial lungs of the country.

- The Hanseatic North: Hamburg remained the gateway to the world, even though its traditional hinterland in the east was cut off.

- The Southern Shift: High-tech manufacturing took root in the "Ländle" (Baden-Württemberg).

Why the Map Still Matters in 2026

You might think the map of West Germany is a relic. It’s not. If you look at a modern map of German wealth, voting patterns, or even the density of high-speed internet, that old 1989 border reappears like a ghost.

Economists often point to the "West-East Divide." Even decades after reunification, the old West German map still outlines where the majority of the DAX companies are headquartered. The infrastructure—the Autobahn networks and the rail lines—still flows toward the old hubs of Bonn and Frankfurt.

📖 Related: Why Palacio da Anunciada is Lisbon's Most Underrated Luxury Escape

Actually, if you’re a hiker today, you can walk the "Grünes Band" (Green Belt). This is the former "death strip" that has been turned into a massive nature reserve. The map of West Germany’s eastern edge is now one of the most biodiverse regions in Europe because, for forty years, nobody was allowed to touch the land. Nature took over where the tanks used to sit.

Mapping Your Own Historical Trip

If you want to actually see this map in the real world, you can't just look at a GPS. You have to go to the places where the map felt the most "real."

- Point Alpha: Located between Hesse and Thuringia, this was considered the "hottest" spot on the map during the Cold War. It was the Fulda Gap, where NATO expected a Soviet tank invasion.

- The Berlin Airlift Memorials: These are scattered across the old Western zones (like Frankfurt’s Rhein-Main Air Base), marking the flight paths that kept the "island" of West Berlin alive.

- The Rhine Valley: Drive from Bonn to Koblenz. This is the heart of the "Old Federal Republic" aesthetic—castles, vineyards, and the quiet diplomacy of the 1950s.

The map of West Germany was never meant to be permanent. It was a placeholder that lasted for 41 years. It shaped the identity of a generation who grew up looking east toward a wall and west toward the Atlantic. Understanding that map is the only way to truly understand why modern Germany behaves the way it does—cautious, decentralized, and forever haunted by the lines drawn in the dirt by four conquering armies.

To get the most out of this history, don't just look at a modern political map. Find a vintage "Shell" road map from the 70s. Look at the way the roads simply vanish when they hit the eastern border. It’s a haunting reminder of how easily a map can be broken—and how hard it is to stitch it back together.

Next Steps for History Buffs:

- Visit the Haus der Geschichte in Bonn: This museum specifically chronicles the life of the Federal Republic. It's the best place to see the original physical maps used by planners in the 1940s.

- Explore the "Grenzmuseen" (Border Museums): Smaller museums like the one in Helmstedt-Marienborn offer a visceral look at the old border crossings.

- Check out the "Grünes Band" hiking trails: You can literally walk the entire length of the old West German eastern border, seeing firsthand how a military barrier became a wildlife corridor.