Look at a map of USA in 1870 and you’ll realize something pretty quickly: the country was basically a half-finished puzzle. If you’re used to the clean, 50-state geometry of today, the 1870 version looks jagged. Incomplete. It’s a snapshot of a nation trying to find its feet after the bloodiest conflict in its history, and frankly, it's a bit of a mess.

We had 37 states then. Just 37.

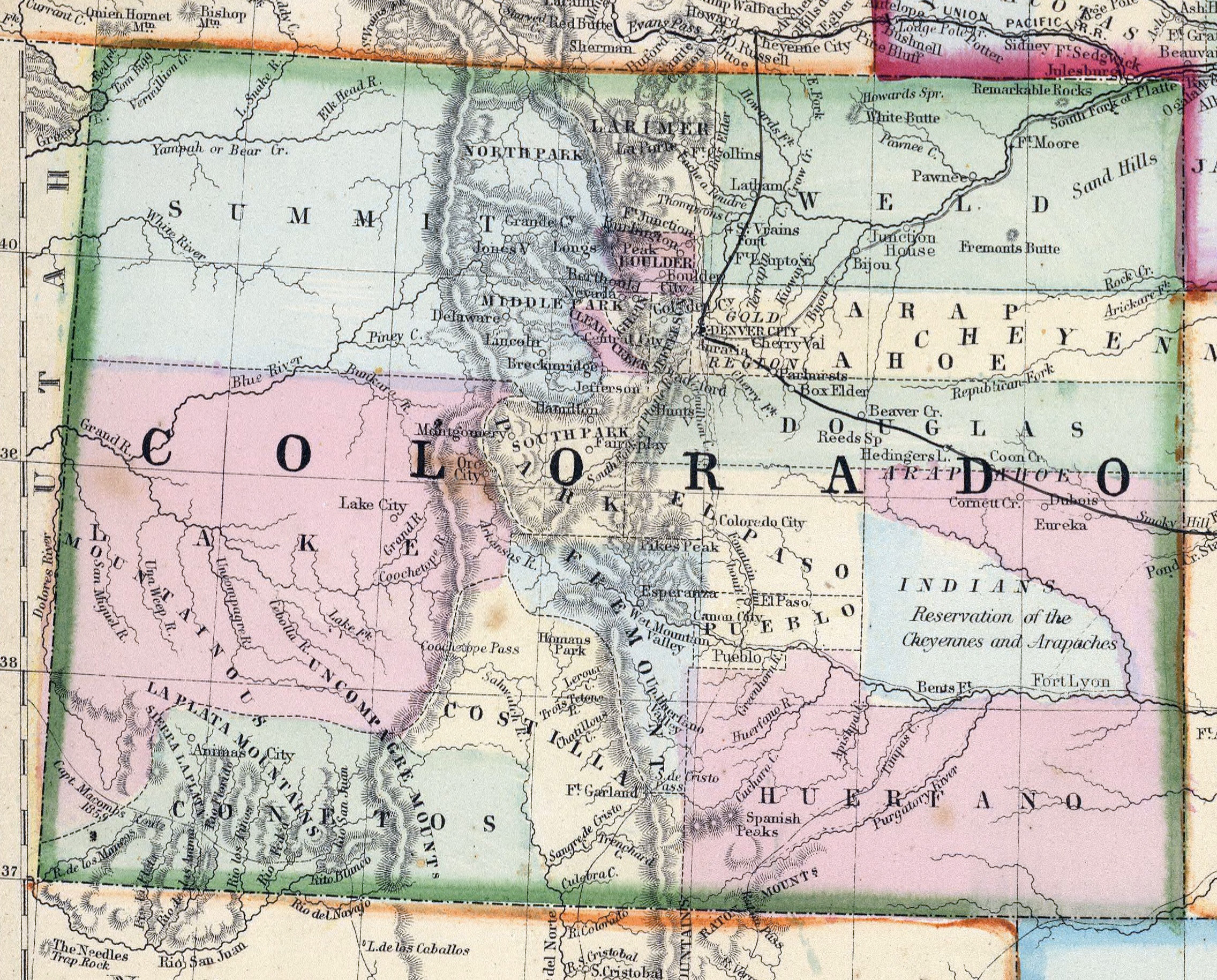

The American West wasn't the West we know. It was a collection of massive, sprawling territories that looked like placeholders. Nebraska had only been a state for three years. Mississippi, Virginia, and Texas were just barely being readmitted to representation in Congress after the Civil War. It’s a map that breathes. It tells you exactly where the power was shifting and where the "empty" spaces—at least in the eyes of the government in D.C.—still remained.

The Ninth Census and the Great Cartographic Shift

1870 was a massive year for American data. It was the year of the Ninth Census. Francis Amasa Walker, a guy who basically revolutionized how we visualize data, took over the Census Bureau and realized that just listing names in a book wasn't enough. He wanted people to see the country.

This led to the creation of the Statistical Atlas of the United States, which is arguably the most important companion to any map of USA in 1870.

Walker's work showed the "frontier line." This was a literal line on the map where the population density dropped below two people per square mile. In 1870, that line was a jagged, vertical scar running through the plains. Beyond that? It was mostly indigenous lands and territorial outposts. You could see the "settlement" creeping westward like a slow-moving tide, mostly following the river valleys and the brand-new tracks of the Transcontinental Railroad, which had been completed just a year earlier in 1869.

Railroads changed everything. Honestly, if you want to understand the 1870 map, you have to ignore the state lines and look at the rail lines. They were the real borders.

The Territories That Refused to Be States

If you look at the center of the map of USA in 1870, you’ll see some familiar names in weird shapes.

💡 You might also like: Finding the most affordable way to live when everything feels too expensive

- Dakota Territory: This was one giant block. No North or South Dakota yet. It was just a massive, windy expanse of prairie that the government hadn't bothered to split up.

- Utah Territory: It was much larger than the current state of Utah. It was still a point of massive friction between the federal government and the Mormon settlers.

- The Unorganized Territory: This is what we now call Oklahoma. Back then, it was a designated space for Native American tribes who had been forcibly relocated. On most maps from 1870, it sits there like a glaring omission, a space "reserved" while the rest of the continent was being sliced into squares.

It’s easy to forget that these weren't states. People living in New Mexico or Arizona in 1870 couldn't vote for President. They didn't have senators. They were essentially colonies of the East.

Reconstruction and the Re-Mapping of the South

The South in 1870 was a legal ghost zone.

While the physical borders hadn't changed, the political map was being rewritten. This was the peak of Reconstruction. You had federal troops stationed in Southern cities. You had the 15th Amendment being ratified in February of 1870, theoretically giving Black men the right to vote.

When you see a map of USA in 1870, you aren't just seeing geography; you're seeing a military occupation.

Texas was readmitted to the Union in March 1870. Mississippi in February. Georgia in July. The map was finally "healing" in a technical sense, but the tension was everywhere. The 1870 census was actually criticized for undercounting people in the South because the region was so chaotic. Some historians, like those at the U.S. Census Bureau themselves, have acknowledged that the 1870 data was probably the most flawed in American history because of the lingering trauma of the war.

What People Get Wrong About the 1870 Map

Most people think the "Wild West" was a lawless void in 1870. That’s not quite right.

By 1870, the map was already being carved up by mining interests and cattle barons. Take a look at Nevada. It became a state in 1864—way before its neighbors—mostly because the Union needed its silver and its electoral votes.

📖 Related: Executive desk with drawers: Why your home office setup is probably failing you

Politics drove the map.

You’ll also notice the "checkerboard" pattern of land ownership. The government was giving away millions of acres to railroad companies. For every mile of track laid, the companies got alternating sections of land. If you could see property lines on a map of USA in 1870, it would look like a giant game of chess played across the plains.

Another huge misconception? The size of cities.

In 1870, Chicago was already a monster, but it hadn't burned down yet (that was 1871). San Francisco was the only real metropolis on the West Coast. Los Angeles? It was a dusty town of about 5,000 people. You could fit the entire population of LA in 1870 into a modern high school football stadium and still have empty seats.

Indigenous Sovereignty vs. Cartography

Here is the thing: the 1870 map is a lie of omission.

It shows "Washington Territory" or "Wyoming Territory," but it doesn't show the Great Sioux Reservation or the Comanchería. In 1870, the U.S. was still signed into treaties that recognized tribal sovereignty over massive chunks of that map.

But the mapmakers didn't care.

👉 See also: Monroe Central High School Ohio: What Local Families Actually Need to Know

They drew lines over ancestral lands as if the people living there didn't exist. This was the era of the "Peace Policy" under President Grant, which was anything but peaceful. It was an attempt to settle tribes on reservations to make the map "cleaner" for white expansion. When you look at the map, you’re looking at a blueprint for displacement.

The Practical Legacy of the 1870 Borders

Why does this matter now? Because those 1870 lines created the water wars of the 2000s.

The guys drawing the map in 1870—people like John Wesley Powell—actually warned the government. Powell explored the Colorado River in 1869 and told everyone that the Western borders shouldn't be straight lines. He argued they should follow watershed boundaries.

He was ignored.

Instead, we got the square states we have today. Because we used a ruler instead of a river to draw the map of USA in 1870, we now have states like Arizona, Nevada, and California fighting over every drop of the Colorado River. The map was designed for easy land sales, not for actual survival in an arid climate.

How to Read an 1870 Map Today

If you’re looking at an original 1870 print, maybe a Colton or a Mitchell map, check the details.

- The "Indian Territory" borders: Notice how they shrink every decade.

- The Railroad Spurs: See how the towns only exist where the water and the coal stops were.

- The Ghost States: Look for "Jefferson" or "Deseret"—names of states that people wanted to create but that D.C. shot down.

The 1870 map isn't a static image. It’s a high-stakes negotiation caught on paper. It’s the moment America stopped being a collection of coastal colonies and truly became a continental empire, for better or worse.

If you want to dive deeper into this, your next move should be to check out the Library of Congress Digital Collections. Search for "Colton's 1870 Map of the United States." You can zoom in close enough to see individual stagecoach routes. It’s a rabbit hole, but it’s the only way to see the country before the highways and the strip malls smoothed everything over.

Alternatively, look up the 1870 Statistical Atlas by Francis Amasa Walker. It’s the first time the U.S. used "heat maps" to show things like where people were illiterate or where malaria was most common. It’s fascinating, slightly depressing, and utterly human. It turns the flat map into a living organism. Read it, and you’ll never look at a "square" Western state the same way again.