History isn't just dates and dead guys. It's lines in the dirt. If you pull up a map of US before Civil War eras, you aren’t looking at the fifty neat boxes we have today. You’re looking at a powder keg. Honestly, it’s a mess of territories, disputed borders, and "unorganized" land that tells the real story of why the country eventually snapped.

The 1850s were weird. People think the map was static, but it was basically vibrating with tension.

Take a look at the massive chunk of land labeled "Kansas Territory" in 1854. It wasn't just a future state; it was a literal battleground. The map changed because people were moving faster than the government could draw the lines. You had the Missouri Compromise of 1820 trying to keep things chill by drawing a line at 36°30′, but by the time the 1850s rolled around, that line was basically garbage.

The Massive Gray Areas on the 1850s Map

Most people forget that a huge portion of what we call the West was just... empty space on the official documents. Well, not empty—Indigenous nations lived there—but the federal government called it "Unorganized Territory."

Look at the Nebraska Territory in 1854. It was humongous. It took up parts of what are now Montana, the Dakotas, Wyoming, and Colorado. When you see a map of US before Civil War tensions peaked, you see these giant blocks of land that hadn't been carved into states yet. Why? Because every time a new state was added, the whole "slave vs. free" balance in the Senate went into a tailspin.

It was a math problem. A scary one.

The 1850 Compromise tried to fix things by bringing in California as a free state. But to make the South happy, the mapmakers had to create the Utah and New Mexico territories without any rules about slavery. They called it "popular sovereignty." Basically, "let the people there fight it out." It sounds democratic, but on the ground, it was a disaster.

👉 See also: Clayton County News: What Most People Get Wrong About the Gateway to the World

Texas Was Even Bigger (Briefly)

You've probably seen the "Old Texas" shape. Before the Compromise of 1850, Texas claimed a massive chunk of what is now New Mexico, including Santa Fe. They even claimed parts of Colorado and Wyoming.

Imagine a map where Texas looks like it’s trying to swallow the Southwest. The federal government eventually paid Texas $10 million to give up those claims and settle into the "panhandle" shape we recognize now. That money helped Texas pay off its debts from its days as a Republic, but the border shift was purely about keeping the peace between North and South. It didn't work for long.

Why the Gadsden Purchase Mattered

In 1853, the map shifted again at the very bottom. James Gadsden, a railroad man, negotiated a $10 million deal with Mexico for a tiny strip of land in what is now southern Arizona and New Mexico.

Why buy a bunch of desert?

Railroads. The South wanted a transcontinental railroad that didn't have to go through the snowy Rocky Mountains. If you look at a map of US before Civil War expansion ended, that little sliver of land represents the last major piece of the "lower 48" puzzle. It also represents the desperate attempt by Southern politicians to expand their influence toward the Pacific.

Bleeding Kansas and the Death of the 36°30′ Line

The most dangerous spot on the map wasn't the South. It was the middle.

✨ Don't miss: Charlie Kirk Shooting Investigation: What Really Happened at UVU

The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 is the moment the map became a weapon. It scrapped the old Missouri Compromise line. Suddenly, two new territories—Kansas and Nebraska—were open to the possibility of slavery based on a vote.

Maps from this era are fascinating because they show "Bleeding Kansas." You had pro-slavery "Border Ruffians" from Missouri crossing over and anti-slavery "Jayhawkers" setting up their own towns. There were literally two different governments in Kansas for a while. If you were looking at a political map in 1856, you wouldn't see a stable territory; you'd see a zone of active insurgency.

The 1860 Election Map: A Country Split Four Ways

By the time 1860 hit, the map looked like a shattered mirror. This wasn't a two-party system.

- Abraham Lincoln took the North and the West Coast.

- John C. Breckinridge swept the Deep South.

- John Bell (the "Constitutional Union" guy) took the middle ground—Tennessee, Kentucky, Virginia.

- Stephen Douglas... well, he only won Missouri.

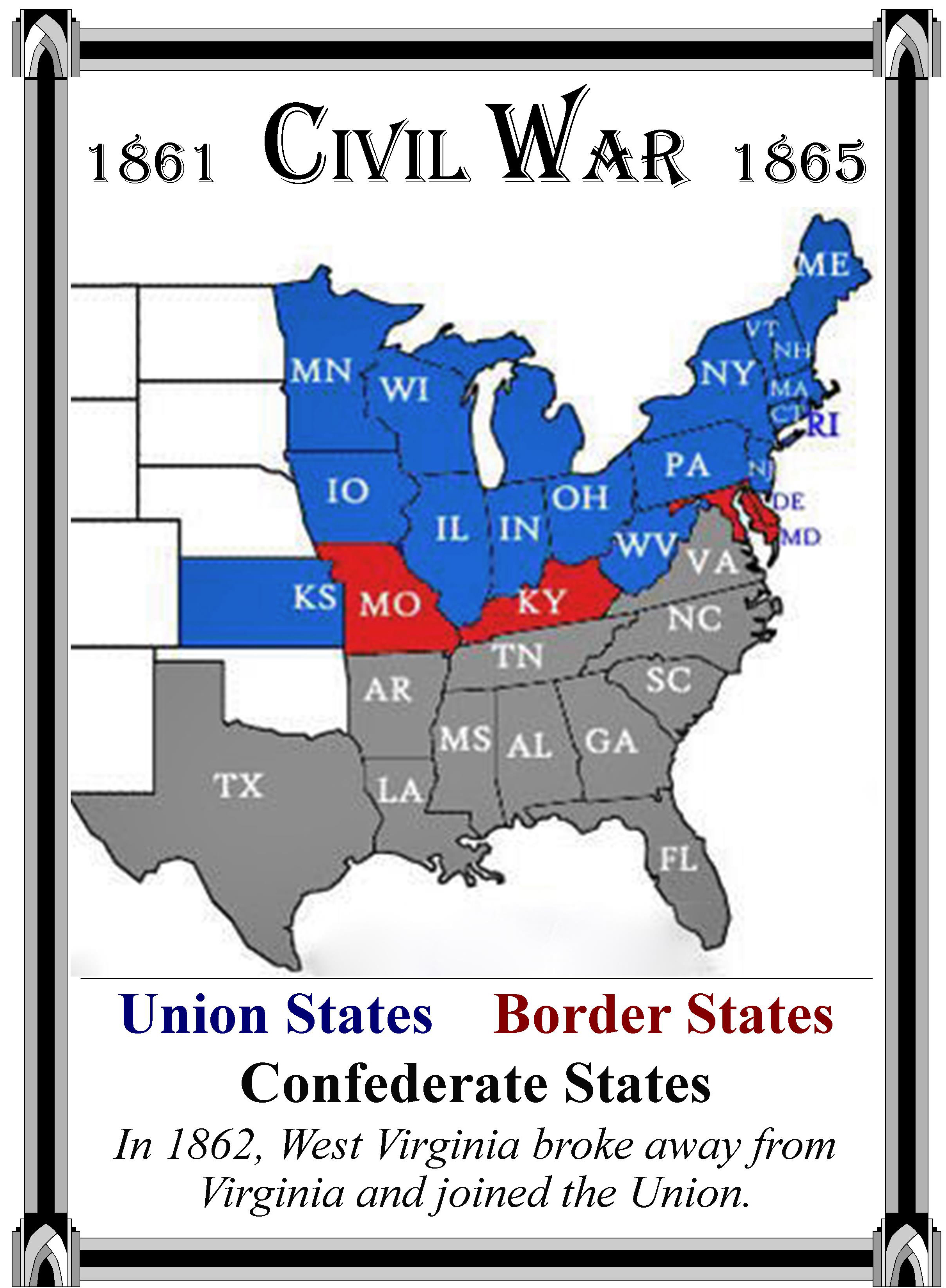

When you overlay the 1860 election results onto the physical map of US before Civil War hostilities broke out at Fort Sumter, the geography of the war becomes obvious. The "Border States" like Kentucky and Maryland were geographically stuck in the middle. They were slave states that didn't secede, creating a weird, tense buffer zone that doesn't fit into the neat "North vs. South" narrative.

Nuance in the Western Territories

We often ignore Oregon and California in this era. California had been a state since 1850, but it was geographically isolated. To get there, you either spent months in a wagon or took a boat around South America.

Oregon became a state in 1859. Its constitution actually banned Black people from entering the state entirely—free or enslaved. This is a gritty detail people often skip. The "Free Soil" movement wasn't always about the morality of ending slavery; for many, it was about keeping the new map "white-only."

🔗 Read more: Casualties Vietnam War US: The Raw Numbers and the Stories They Don't Tell You

The maps we see in school textbooks usually use blue for North and red for South. It’s too simple. The reality was a spectrum of gray.

Examining the 1861 Secession Map

Once South Carolina left in December 1860, the map started to crumble. But it didn't happen all at once. There was a "first wave" of secession (the Deep South) and a "second wave" (the Upper South) that only left after Lincoln called for troops.

Virginia is the craziest part of this map. The state literally split in half. The western counties didn't want to leave the Union, so they broke away to form West Virginia. This is one of the only times in American history where the map changed because a state decided to secede from its own secession.

Key Takeaways for History Buffs

If you’re studying a map of US before Civil War eras, don't just look at the states. Look at the trails. The Oregon Trail, the Santa Fe Trail, and the proposed railroad routes were the veins of the country.

- The territories were huge. Modern states like Oklahoma were "Indian Territory," a place where the government had forcibly moved tribes like the Cherokee and Choctaw, only to later squeeze them as white settlers pushed west.

- The borders were fluid. The border between the US and Mexico had only been settled in 1848 (Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo) and 1853.

- Population density was lopsided. The North had the rail lines and the cities. The South had the river systems and the plantations. You can see this on "Census Maps" from 1860, which are some of the first data-driven maps in US history.

Practical Steps for Further Research

To truly understand this period, you need to look at "The Coast Survey of 1861." It’s a famous map showing the distribution of the enslaved population.

- Search the Library of Congress digital archives. They have high-resolution scans of the 1860 Mitchell's New National Map. You can zoom in and see individual towns that no longer exist.

- Compare a physical map with a railroad map from 1858. You'll see why the North had such a massive logistical advantage. The spiderweb of tracks in Ohio and Pennsylvania compared to the sparse lines in Georgia tells the whole story of the war's outcome before a single shot was fired.

- Look up "The Colton Map" from 1855. It’s arguably the most beautiful and detailed map of that decade, showing the transition from "wild" territories to organized counties.

The map didn't just show where people lived. It showed what they were willing to die for. By the time 1861 rolled around, the lines had been drawn so deeply that only a war could move them again.