If you look at a map of United States in 1812, you might get a little dizzy. It’s messy. Honestly, it looks like a half-finished jigsaw puzzle where the pieces don't quite fit yet. You’ve got the original thirteen colonies-turned-states hugging the Atlantic, a massive, vaguely defined chunk of dirt called the Louisiana Purchase, and then a whole lot of "we’ll figure it out later."

The country was an adolescent. Awkward. Growing too fast for its clothes.

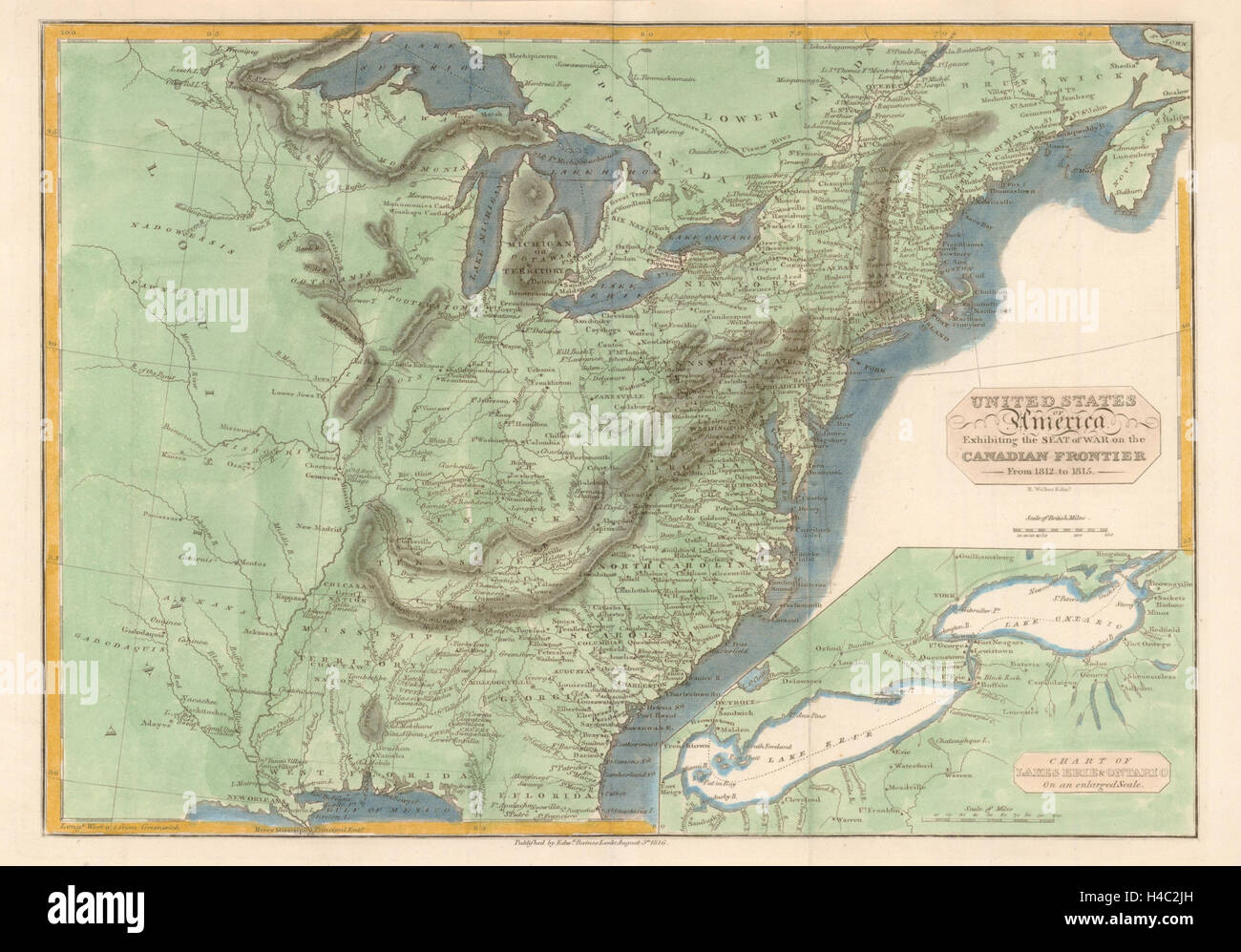

When people search for this specific map, they’re usually looking for the theater of war. They want to see where the British burned DC or where Andrew Jackson stood his ground in New Orleans. But the map is actually a story of legal confusion and overlapping claims. It wasn't just a quiet period before the West was won; it was a chaotic era where the borders were drawn in pencil, not ink.

The Disappearing Borders of 1812

Let's be real: the map of United States in 1812 is basically a snapshot of a country in an identity crisis. You had 18 states by the time the war started. Louisiana had just squeezed in as the 18th state in April of 1812, right before the shooting started.

But look closely at the edges.

The northern border with British North America (now Canada) was a disaster. Nobody really knew where the line was in the Great Lakes or the woods of Maine. This lack of clarity is exactly why so much of the War of 1812 was fought on the edges of the map. You had the Michigan Territory, the Illinois Territory, and the Indiana Territory. These weren't states. They were vast, sparsely populated regions where the federal government had a very loose grip.

The maps of the era, like the ones printed by John Melish, showed a nation that was physically enormous but politically thin. Melish’s 1812 map was one of the first to really show the U.S. stretching across the continent, even if the "state" parts were mostly stuck on the East Coast.

That Massive "Unorganized" Middle

The Louisiana Purchase had happened less than a decade earlier. In 1812, most of that land was just the Missouri Territory. It was a giant blob on the map.

✨ Don't miss: The Long Haired Russian Cat Explained: Why the Siberian is Basically a Living Legend

If you were a settler in 1812, you weren't looking at a GPS. You were looking at rivers. The Mississippi and the Missouri were the highways. If you weren't near water, you weren't on the map. This is a crucial distinction. We think of maps as solid blocks of color today, but back then, the map of United States in 1812 was really just a collection of river settlements and wagon trails surrounded by "unknown" territory.

Why the Map of United States in 1812 Still Matters

It’s about the tension.

The British still held forts in the Northwest Territory—land that was technically American on paper but British in reality. This "paper vs. reality" gap is the defining characteristic of the 1812 landscape. You see, the British were backing Native American confederacies, like the one led by Tecumseh, to create a "buffer state" between the U.S. and Canada.

Imagine that.

A third country right in the middle of the Great Lakes region. If the War of 1812 had gone differently, the map of United States in 1812 wouldn't have been a stepping stone to the Pacific; it might have been the furthest the U.S. ever got. The "Old Northwest" (Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin) was the front line.

The Spanish Floridas and the Southern Mess

Down south, things were even weirder.

Florida wasn't a state. It wasn't even American. It was Spanish. But Spain was a mess because of Napoleon back in Europe, so the U.S. just... took bits of it. We called it "West Florida." By 1812, the U.S. had basically annexed the area around Mobile and Biloxi, even though the official map-makers in Madrid were screaming "No!"

🔗 Read more: Why Every Mom and Daughter Photo You Take Actually Matters

This is why looking at a map of United States in 1812 is so important for understanding American expansion. It wasn't some polite, organized process. It was a series of land grabs, border disputes, and "oops, this is ours now" moments.

The Cartography of Conflict

The war itself changed how people viewed the land. Before 1812, a lot of Americans didn't really care about the interior. After the British started invading from the sea and the north, the map became a matter of national security.

- The Great Lakes: This was the naval heart of the war. Lake Erie and Lake Ontario were the primary battlegrounds.

- The Chesapeake: A vulnerable "inland sea" that let the British sail right up to the front door of the White House.

- The Gulf Coast: A chaotic mix of Spanish, British, American, and Pirate (shoutout to Jean Lafitte) influences.

When you look at a map from this specific year, you see the vulnerability. The coastlines are long and undefended. The interior is disconnected. It’s a miracle the country stayed together at all, frankly.

Misconceptions About the 1812 Border

One huge mistake people make is thinking the 49th parallel was the border yet. It wasn't. That didn't happen until 1818. In 1812, the border in the West was "to be determined." The Oregon Country was a shared mess between the U.S. and Britain.

Actually, many maps of the time just stopped. They didn't even show the West Coast.

How to Read an 1812-Era Map Today

If you find a high-resolution scan of a map from 1812, don't look for the cities. Look for the "Indian Nations." Unlike modern maps that erase indigenous presence, 1812 maps often explicitly labeled territories belonging to the Cherokee, Creek, and Choctaw in the South, or the Wyandot and Shawnee in the North.

These were sovereign powers.

💡 You might also like: Sport watch water resist explained: why 50 meters doesn't mean you can dive

The map of United States in 1812 was a multi-polar map. It wasn't just "US vs Britain." It was a complex web of tribal lands, colonial remnants, and emerging states.

- Check the Date: Maps printed in early 1812 won't show Louisiana as a state.

- Look at the "Districts": Maine was still part of Massachusetts. It’s weird to see, but Maine doesn't become its own thing until 1820.

- Find the "Wilderness": Check out the area that is now Georgia and Alabama. It was mostly Mississippi Territory back then.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs and Researchers

If you're trying to use a map of United States in 1812 for a project, or you're just a nerd for this stuff, keep these things in mind.

First, use the Library of Congress digital archives. They have the high-res T. G. Bradford and John Melish maps that actually show the "boots on the ground" reality. Don't trust modern "recreations" that use clean lines—the real maps were full of notes about "impassable swamps" and "unexplored hills."

Second, compare an 1812 map to an 1820 map. The jump is insane. In those eight years, the map solidifies. The War of 1812 was the catalyst that forced the U.S. to actually define its borders instead of just guessing where they were.

Finally, visit the actual locations. If you stand on the shores of Lake Erie at Put-in-Bay, you aren't just looking at water; you’re looking at the spot where the map was literally redrawn with cannons.

The map of United States in 1812 isn't just a piece of paper. It’s a blueprint of a country that almost didn't make it. It's a reminder that borders are fragile and that "Manifest Destiny" wasn't a sure thing—it was a gamble.

To get the most out of your research, download a high-resolution version of the 1812 Melish Map. Study the "Western Territory" and note how little the government actually knew about the land they "owned." Then, cross-reference those locations with modern topographical maps to see how the landscape—rivers, forests, and shorelines—has shifted over the last two centuries. This gives you a much better sense of the logistical nightmares faced by soldiers and settlers alike during the war.