If you try to look up a map of Underground Railroad routes today, you’re probably going to see a bunch of tidy, solid lines. Most of them point straight north. They look like modern highway maps, stretching from the deep South up into Canada. Honestly, those maps are kinda lying to you.

History isn't a GPS coordinate. The "Underground Railroad" wasn't a literal railroad, obviously, but it wasn't a fixed set of secret backroads either. It was a shifting, terrifying, and deeply spontaneous network of human bravery. You've got to understand that in 1850, drawing a map of these routes would have been a death warrant for everyone involved.

The Myth of the "Fixed Route"

Most people think of the map of Underground Railroad paths as a permanent infrastructure. We imagine Harriet Tubman or William Still sitting down with a compass and marking out "Station A" to "Station B." That’s just not how it worked.

The "map" existed mostly in the heads of the "conductors" and the "passengers." It changed based on the weather, the height of the rivers, and how many bounty hunters were currently hanging out at the local tavern. If a certain safe house—a "station"—got burned or the owner got twitchy, that route vanished. Just like that. A new one had to be forged through a swamp or a different cornfield.

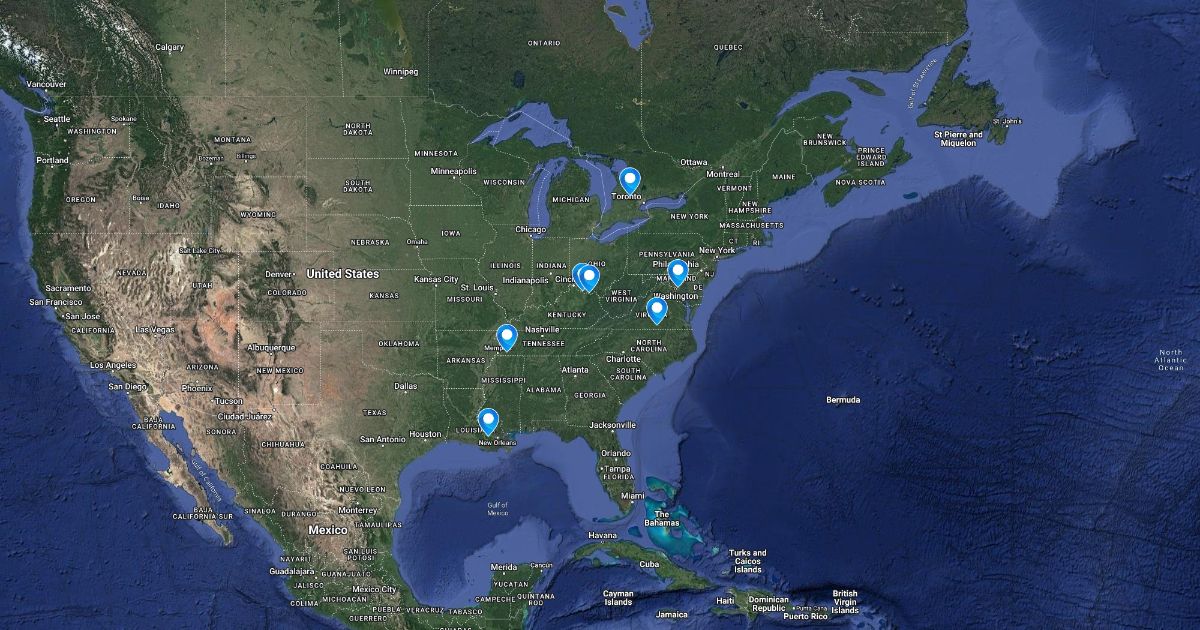

Think about the sheer scale of the risk. After the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, escaping didn't just mean getting to Ohio or Pennsylvania. It meant you weren't safe until you crossed the border into Ontario, Canada. This law basically turned the entire North into a hunting ground for enslavers. So, a map of Underground Railroad activity from 1840 looks radically different from one in 1855. The lines had to get longer. The risks got exponentially higher.

It Wasn't Just One Way

We always look at the North Star. Follow the drinkin' gourd, right? But the reality is that the map of Underground Railroad escapes actually points in every direction.

- Southbound to Mexico: If you were enslaved in Texas or Louisiana, you didn't go to Canada. You went south. Mexico had abolished slavery in 1829. There was a massive, often overlooked network of Tejanos and Black freedom seekers moving toward the Rio Grande.

- The Caribbean Option: People in Florida often escaped by sea. They went to the Bahamas or stayed in the Everglades with the Seminole tribes.

- Western Frontiers: Some headed toward California or Oregon, hoping the chaos of the frontier would provide a screen.

Why Geography Was the Biggest Enemy

You can’t talk about these maps without talking about the terrain. Modern maps make it look like a long walk. It wasn't just a walk. It was a nightmare of physical endurance.

👉 See also: Why the Man Black Hair Blue Eyes Combo is So Rare (and the Genetics Behind It)

Take the Appalachian Mountains. If you’re looking at a map of Underground Railroad routes through Western Pennsylvania or Virginia, you’re looking at some of the most punishing elevation changes in the eastern United States. Freedom seekers weren't using the nice, flat gaps. They were moving through the thickest brush to stay out of sight.

Rivers were both a blessing and a curse. The Ohio River is the most famous boundary on any map of Underground Railroad history. It was the "River Jordan." But crossing it wasn't always a matter of finding a boat. In the winter, if it froze, you could walk across. If it flooded, you were trapped on the southern bank, praying the "station master" on the other side saw your signal fire.

The Urban Map vs. The Rural Map

The way people hid in Philadelphia or New York was totally different from how they hid in the woods of Maryland. In cities, the "map" was a list of addresses. 131nd Street in Manhattan. The Johnson House in Germantown. These were places where you could blend into a crowd.

In the woods? The map was the moss on the north side of a tree. It was the sound of a specific bird call used as a signal.

Real Names You Should Know (Beyond Harriet Tubman)

We talk about Harriet a lot, and for good reason. She was a genius. But the map of Underground Railroad success was built by thousands of people whose names are barely in the archives.

William Still is the guy you really need to look up. He was based in Philadelphia and kept meticulous records—which was incredibly dangerous. He eventually published them, and that's how we have any factual basis for these maps today. He recorded the stories, the aliases, and the family connections.

✨ Don't miss: Chuck E. Cheese in Boca Raton: Why This Location Still Wins Over Parents

Then there’s Levi Coffin, a Quaker in Indiana and Ohio. His home was called the "Grand Central Station" of the Underground Railroad. When you look at a map of the Midwest's routes, almost all of them eventually funnel through his neck of the woods. He claimed to have helped over 3,000 people.

The Role of Free Black Communities

It’s a common misconception that the map was mostly white Quakers helping out. While many did, the backbone of the network was free Black communities. Places like "Mother Bethel" AME Church in Philadelphia were the true hubs. These were the spots where you could get a new set of clothes, some fake papers, and a meal that wouldn't get you turned in.

How to Read a Modern Map of the Underground Railroad

If you’re looking at a map online today, check the sources. National Park Service (NPS) maps are generally the gold standard because they require "documented proof" of activity. But here's the catch: because the Railroad was secret, "documented proof" is hard to find.

A lot of local legends about "secret tunnels" in old houses are actually just old root cellars. People love the idea that their basement was a stop on the railroad. Sometimes it was! But often, the real history is more about a person being hidden in an attic or a barn for two days before being moved in a wagon under a pile of hay.

- Check for the "Network to Freedom" logo: The NPS uses this to verify authentic sites.

- Look for Waterways: If the map doesn't emphasize the importance of the Chesapeake Bay or the Ohio River, it's missing the point.

- Search for "Lines of Flight": This is a term historians use to describe the general direction of escape rather than a specific road.

The Logistics of the Journey

It’s easy to get lost in the romance of the story, but the logistics were brutal. Imagine trying to coordinate a hand-off between three different people who don't have phones, don't have a shared map, and can't be seen talking to each other.

The "map" was often communicated through song or coded language. When someone talked about "the wind blowing from the north," they weren't always talking about the weather. They were talking about an opportunity.

🔗 Read more: The Betta Fish in Vase with Plant Setup: Why Your Fish Is Probably Miserable

The Cost of a Wrong Turn

One wrong turn on the map of Underground Railroad routes meant the difference between life and death—or worse, a return to enslavement. The rewards for capturing "runaways" were massive. A single person could be worth a year's salary to a bounty hunter. This meant that the "map" had to include "danger zones."

Courthouses, busy ports, and certain counties known for their aggressive slave-catchers were marked in the minds of conductors as "no-go" areas. This forced the routes to be jagged and inefficient.

Why We Still Study These Maps

Understanding the map of Underground Railroad activity isn't just a history lesson. It's a study in grassroots organizing. It shows how a group of disorganized, persecuted, and often poor people built a system that defeated the most powerful economic engine of its time.

They didn't have a central command. They didn't have a budget. They just had a shared map of morality and a lot of guts.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs

If you actually want to see this history for yourself, don't just look at a screen. Get out and follow the geography.

- Visit the Cincinnati Freedom Center: It sits right on the bank of the Ohio River. Standing there and looking across to Kentucky gives you a perspective no map can provide.

- Explore the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Historical Park: This is in Maryland. The landscape there—the marshes and the woods—looks much like it did in the 1850s. You'll see why it was so easy to get lost and so hard to be found.

- Research your own town: Use the National Park Service Network to Freedom database. You might find that a map of Underground Railroad stops actually goes right through your own backyard.

- Read the primary sources: Pick up The Underground Railroad Records by William Still. It’s heavy, it’s long, and it’s the closest thing to a "real" map you'll ever find.

The truth is, the map of Underground Railroad history is a map of the American spirit. It's messy, it's incomplete, and it's full of holes. But that's exactly what makes it real. It wasn't a project of a government; it was the project of people who refused to accept the world as it was.

To truly understand these routes, you have to stop looking for straight lines and start looking for the courage it took to step into the dark without a map at all.