It is a mess. Honestly, looking at a map of the United States in 1861 feels like looking at a puzzle that someone sat on and then tried to put back together while the room was on fire. Most people think of the Civil War as a neat "North vs. South" split, but the geography was way more chaotic than your high school history teacher probably let on. You’ve got territories that don't exist anymore, states that hadn't found their final shapes, and a massive chunk of the West that was basically a giant "to be determined" sign.

The map didn't just change; it shattered.

When Abraham Lincoln took the oath of office in March, the country was physically disintegrating. By the time the first shots were fired at Fort Sumter in April, the cartography of the continent was a political nightmare. You weren't just looking at state lines. You were looking at a visual representation of a national nervous breakdown.

The Disappearing Act: When the South Walked Off the Map

The most jarring thing about a map of the United States in 1861 is the sheer speed of the erasure. Seven states—South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas—had already "left" by the time the year really got moving. They formed the Confederate States of America (CSA). Later, after the fighting started, Virginia, Arkansas, North Carolina, and Tennessee joined them.

But here is where it gets weird.

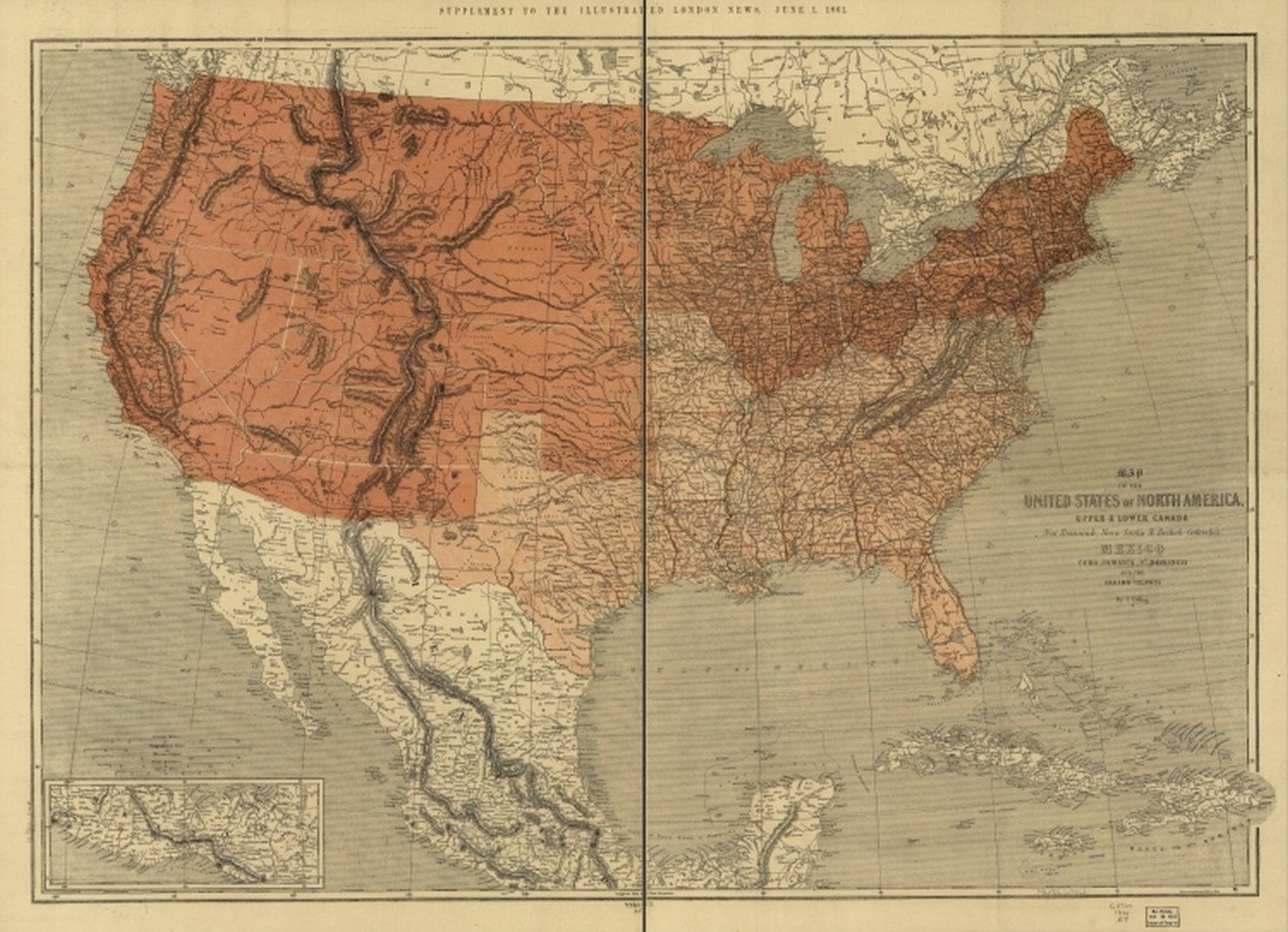

If you look at a Union-printed map from 1861, they often refused to acknowledge the CSA existed at all. They just kept printing the old borders as if nothing happened. It was a form of cartographic denial. On the flip side, Confederate maps started claiming territories like New Mexico and Arizona, even though they barely had any troops there. It was a war of ink and paper before it was a war of bullets.

👉 See also: Why are US flags at half staff today and who actually makes that call?

The "Border States" are the real headache for anyone trying to draw a clean line. Missouri, Kentucky, Maryland, and Delaware were slave states that stayed in the Union. If you look at a map from the summer of 1861, these states are shaded in this awkward "middle ground" color. They were the buffer zone. Without them, the Union probably would have lost Washington D.C. in the first week, because Maryland literally surrounds the capital.

The West Was a Total Wild Card

While everyone was staring at the East Coast, the West was a chaotic sprawl. In 1861, Kansas finally became a state, but it did so right as the world was ending. Meanwhile, the Dakota Territory was created in March. It was huge. It encompassed what we now know as North and South Dakota, plus huge chunks of Montana and Wyoming.

The map of the United States in 1861 shows Nevada as a brand-new territory, sliced away from Utah. Why? Because the Union needed the silver. They also didn't trust the Mormons in Utah to stay loyal, so they shrank their borders to keep them in check. It was a map drawn by suspicion.

Then you have the "Confederate Territory of Arizona." Most people forget this. In 1861, Southern sympathizers in the southern half of the New Mexico Territory (which back then included Arizona) held a convention and declared themselves part of the Confederacy. For a brief window, the CSA actually reached all the way to the California border. It didn't last, but it’s a wild thing to see on a period-accurate map.

The Virginia Breakup Nobody Saw Coming

Look closely at the Appalachian Mountains on an 1861 map. You won't see West Virginia. Not yet. But you can see the cracks forming.

✨ Don't miss: Elecciones en Honduras 2025: ¿Quién va ganando realmente según los últimos datos?

Virginia was the most powerful state in the South, but the folks living in the western mountains had zero interest in fighting for a plantation economy they didn't belong to. By mid-1861, they were already holding meetings in Wheeling to figure out how to secede from the secessionists. It’s one of the few times in history where "I'm leaving because you're leaving" actually resulted in a permanent new state.

The geography was the destiny here. The mountains acted as a natural barrier. While the flatlands of eastern Virginia were perfect for tobacco and slave labor, the rugged west was small-farm territory. The map was literally being torn in half by the terrain itself.

Why the 1861 Map Still Messes With Our Heads

The reason this specific year is so important for collectors and historians is that it represents the "Old World" and the "New World" colliding. It’s the last time the map felt like an experiment rather than a finished product.

- The Railroad Influence: Look at the lines on an 1861 map. You’ll see the spiderweb of tracks in the North and the sparse, disconnected lines in the South. This wasn't just about travel; it was about logistics. The North’s map was built for industrial war; the South’s map was built for rural isolation.

- The Indigenous Reality: We often look at these maps and see empty space in the West. It wasn't empty. It was Indigenous land that the U.S. government was labeling as "Territories" to claim ownership on paper. In 1861, the federal government was so distracted by the Civil War that their control over these Western maps was almost entirely theoretical.

- The Postal Service Factor: Surprisingly, the Post Office is why we have such good records of these maps. They needed to know where they could still deliver mail. When the map changed, the mail stopped. In May 1861, the U.S. Postmaster General officially suspended service to the seceded states.

How to Spot a "Fake" or Modernized 1861 Map

If you are looking for an authentic map of the United States in 1861, you have to watch out for "cleanliness." Modern recreations often make the borders look too settled. Real maps from 1861 often have weird annotations. They show forts that no longer exist or "unorganized" regions that were actually battlegrounds.

Check the "Indian Territory" (modern-day Oklahoma). A real 1861 map will show it as a distinct, unorganized block. Many tribes there actually signed treaties with the Confederacy, which added another layer of complexity to the map that most people totally overlook.

🔗 Read more: Trump Approval Rating State Map: Why the Red-Blue Divide is Moving

The Actionable Insight for History Buffs and Map Collectors

If you're trying to understand the map of the United States in 1861, don't just look at a static image. You need to look at the progression from January to December.

- Compare January to July: You will see the sudden "graying out" of the Southern states.

- Focus on the Transcontinental Route: Notice how the map shows the proposed routes for the railroad. The war actually accelerated this because the North didn't have to argue with the South anymore about where the tracks should go.

- Check the Coastlines: The Union blockade (The Anaconda Plan) effectively turned the Southern coastline into a "no-go" zone on the map. This changed how trade maps were drawn almost overnight.

To truly see what was happening, look for the John Colton or Augustus Mitchell maps from that year. They were the gold standard of 19th-century cartography. You can find high-resolution scans of these at the Library of Congress. Searching their digital archive for "1861" will give you the most honest, unfiltered view of a country that was literally falling apart.

Instead of just looking at the states, look at the topography. Look at the rivers. The Mississippi River was the "spine" of the map in 1861, and whoever controlled it controlled the continent. When you see how the borders hug the water, you realize the war wasn't fought over lines on a map; it was fought over the dirt and the water those lines were trying to claim.

The 1861 map is a snapshot of a moment where everything was up for grabs. It’s a messy, beautiful, and tragic piece of paper that proves geography is never really permanent. It’s just what we agree on for the moment.

To get the most out of your research, download a high-resolution version of the Mitchell’s New National Map (1861). Zoom in on the border between Virginia and the "Western Counties." You can see the specific towns that would soon become the front lines. Seeing those names—Manassas, Richmond, Wheeling—in their original context makes the history feel a lot less like a textbook and a lot more like a real, terrifying event that people had to navigate using these very same pieces of paper.