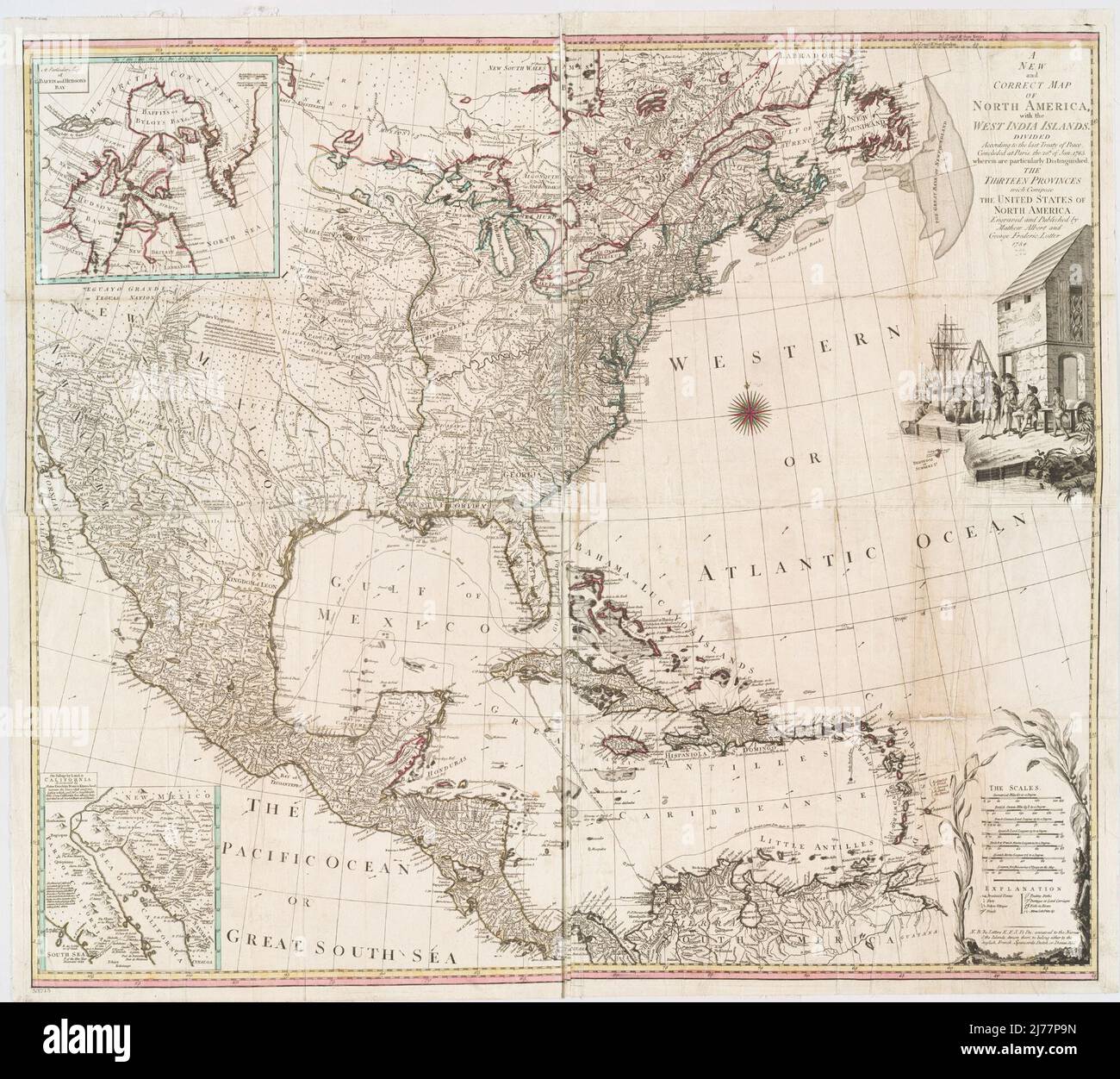

Imagine sitting in a cramped, mahogany-paneled room in Paris. It’s 1783. Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and John Jay are staring at a massive, hand-colored map spread across a table. They aren’t just looking at paper; they are basically playing a high-stakes game of "Risk" with real lives and millions of acres of old-growth forest. The map of the Treaty of Paris 1783 wasn't just a geographical record. It was a messy, optimistic, and occasionally flat-out wrong blueprint for a brand-new nation.

The United States had won the war, sure. But the British weren't just going to hand over a crisp, GPS-verified map of the frontier.

Most people think the American Revolution ended and we just "got" the land east of the Mississippi. It was way more complicated than that. When you look at a map of the Treaty of Paris 1783, you’re looking at a compromise that left everyone a little bit annoyed. The British kept Canada. The Spanish got Florida back (yes, they had it before). And the Americans? They got a giant, vaguely defined chunk of the "Northwest Territory" that would eventually become Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, and Wisconsin.

But there’s a catch. The map they used to decide these things was wrong.

The Mitchell Map: The Most Important (and Inaccurate) Map in History

If you want to understand why our northern border looks like a jagged tooth, you have to look at the Mitchell Map. John Mitchell, a botanist who honestly wasn't the best cartographer, drew this map in 1755. By the time 1783 rolled around, it was the gold standard.

The problem? Mitchell thought the Mississippi River started much further north than it actually does.

Because of this error, the negotiators wrote into the treaty that the boundary would run from the Lake of the Woods "due west" to the Mississippi. You can look at a map today and see the problem: the Mississippi starts south of the Lake of the Woods. You can't go due west to hit it. This single mistake created the "Northwest Angle," that weird little chimney of land that pokes up into Canada from Minnesota. It’s a literal geographical ghost of a 250-year-old clerical error.

💡 You might also like: Brian Walshe Trial Date: What Really Happened with the Verdict

Modern historians like Max Edelson have pointed out that these maps weren't just navigation tools; they were political weapons. The British wanted to limit the U.S. to the Appalachian Mountains. The Americans wanted the whole continent. The final map of the Treaty of Paris 1783 was essentially the middle ground that nobody loved but everyone signed.

What the Map Actually Gave the U.S.

The boundaries were supposed to be clear. They weren't.

Starting from the Atlantic, the border went through the St. Croix River (which people couldn't even agree on the location of for years), then along the highlands dividing the St. Lawrence River from the Atlantic, and through the middle of the Great Lakes. Then it hit that "due west" disaster at the Mississippi.

The southern border was equally tricky. It was set at the 31st parallel. If you look at a map of the Treaty of Paris 1783, you'll see a straight line cutting across what is now Mississippi and Alabama. This was a massive win for the U.S. because it pushed the Spanish (who held Florida) much further south than they wanted to be.

The Forgotten Players: Why the Map is Missing People

One thing you’ll notice if you stare at any official version of the map of the Treaty of Paris 1783 is what—or who—is missing.

Indigenous nations.

📖 Related: How Old is CHRR? What People Get Wrong About the Ohio State Research Giant

The Haudenosaunee (Iroquois), the Miami, the Shawnee—none of them were at the table in Paris. The British basically handed over land that wasn't theirs to give. They just signed away the Ohio Valley and told the Americans, "Good luck with the locals." This created a massive legal and violent conflict that lasted for decades. While the map showed American "ownership," the reality on the ground was a patchwork of sovereign tribal lands that the treaty completely ignored.

This isn't just a "woke" observation; it’s a factual necessity for understanding why the map didn't match reality. The U.S. government spent the next fifty years trying to make the physical map match the legal one through a series of further treaties, purchases, and wars.

The Mystery of the Red-Line Map

There is a famous version of the Mitchell map called the "Red-Line Map." King George III supposedly had his own copy where a thick red line showed the agreed-upon borders. For years, this map was "lost" in the British archives.

Why does that matter?

Because later, during the Maine-New Brunswick border dispute in the 1840s, the British realized the Red-Line Map actually supported the American claim. So, they kind of... hid it. Diplomacy is a dirty business. Eventually, the Webster-Ashburton Treaty of 1842 had to clean up the mess left by the 1783 map. Even today, if you go to the National Archives or the Library of Congress, the versions of these maps you see are often covered in handwritten notes and ink stains that show just how much guessing was involved.

How to Read a 1783 Map Without Getting Confused

If you’re looking at a digital scan of a map of the Treaty of Paris 1783, keep these things in mind:

👉 See also: The Yogurt Shop Murders Location: What Actually Stands There Today

- The "Old Northwest" is the Midwest. When the treaty talks about the Northwest, it means Detroit and Chicago, not Seattle.

- The Maine border is a mess. The "highlands" mentioned in the treaty didn't really exist the way the map showed them.

- The Mississippi is the end of the world. For the 1783 Americans, everything west of the Mississippi was a foreign country (Spain). It’s weird to think of St. Louis as "abroad," but in 1783, it was.

- Florida is huge. The map shows "West Florida" stretching all the way to the Mississippi River.

It’s easy to forget how much of this was speculative. They were carving up a continent based on reports from fur trappers and Jesuit missionaries.

Actionable Steps for History Buffs and Researchers

If you want to actually see these maps or use them for a project, don't just rely on a grainy Google Image search.

First, go to the Library of Congress digital collections and search for the "Mitchell Map." They have high-resolution scans where you can see the actual hand-drawn lines. Look for the 1755 edition, as that’s the one the negotiators actually used.

Second, if you're ever in London, the British Library holds the "King George III copy" of the map. Seeing it in person makes you realize how fragile the birth of the U.S. really was. The ink is fading, the paper is yellowed, and yet this document determines where you pay your taxes if you live in Buffalo or Detroit.

Third, check out the Osher Map Library online. They have incredible overlays that show the 1783 boundaries compared to modern satellite imagery. It’s the best way to see exactly where the 18th-century guys got it wrong.

The map of the Treaty of Paris 1783 isn't just a historical relic. It's the reason why the U.S. is the shape it is today. It’s a testament to the fact that even the most powerful empires in the world can be defeated by a bad drawing and a lot of stubbornness.

When you look at the map now, don't just look at the lines. Look at the gaps. The gaps between what the British thought they were giving, what the Americans thought they were getting, and what the people actually living there knew to be true. It's a document of transition. It marks the moment a collection of colonies became a transcontinental experiment, even if they didn't quite know where the river started yet.

Next Steps for Deep Exploration:

- Locate the Northwest Angle on Google Maps to see the most famous error from the 1783 treaty in modern geography.

- Compare the Proclamation Line of 1763 with the 1783 map to see how much territory the U.S. gained in just twenty years.

- Research the Phelps and Gorham Purchase to see how the land on the 1783 map was actually broken down and sold to settlers.