Space is big. Really big. You’ve probably heard that before, but when you actually try to look at a map of the Milky Way, the sheer scale of our ignorance becomes the first thing you notice. We live inside a giant, dusty disk. Imagine trying to map the floor plan of a massive, smoke-filled skyscraper while you’re pinned to a single chair in a tiny cubicle on the 20th floor. That is essentially the problem face by modern astronomers.

It’s a mess.

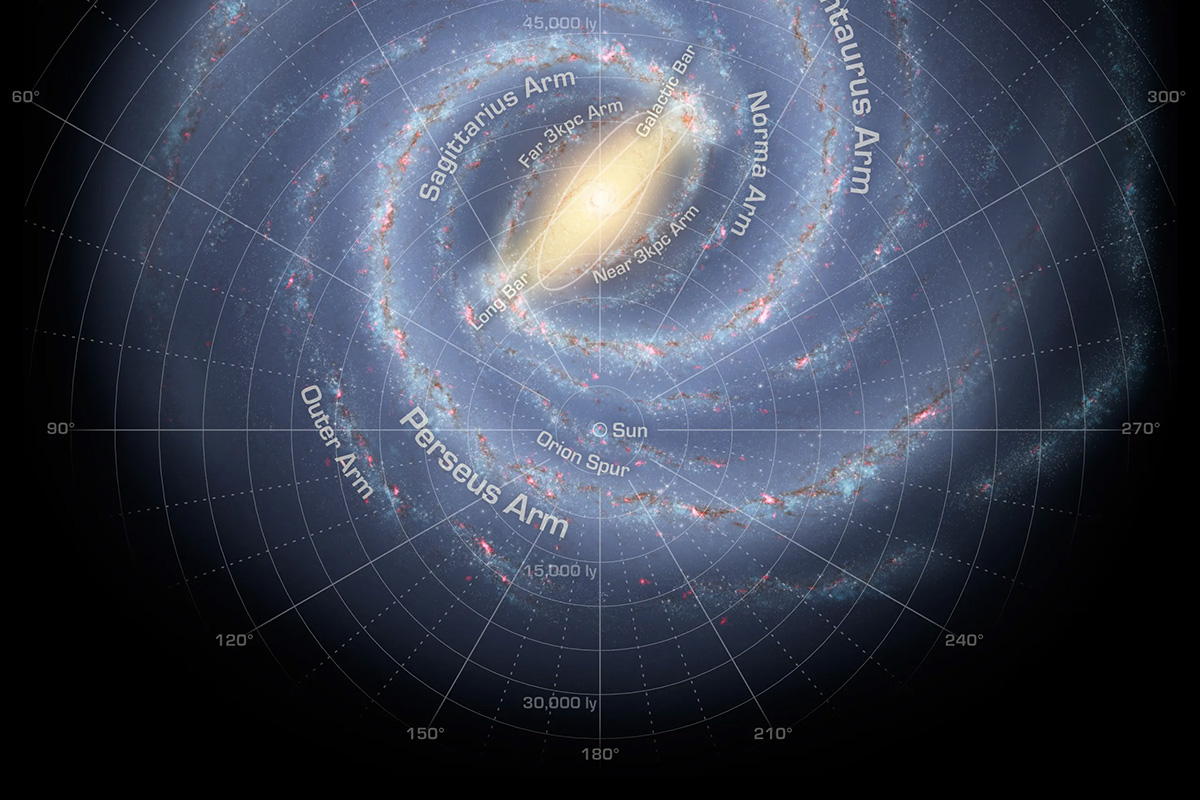

For decades, we relied on artist’s impressions that made our galaxy look like a perfect, symmetrical fried egg with glowing swirls. Those images are mostly lies. Well, "educated guesses" is the polite term. Because we are sitting about 26,000 light-years from the center, we can't just fly a camera "up" to take a selfie of the spiral arms. Instead, we have to use radio waves, infrared sensors, and the sheer grit of projects like the Gaia mission to piece together where things actually sit.

The Gaia Revolution and the End of Guesswork

Before 2013, our map of the Milky Way was kinda sketchy. We knew the general shape, sure, but the distances to individual stars were often off by huge margins. Then the European Space Agency launched the Gaia spacecraft. This thing is a beast. It’s currently parked a million miles away at a point called L2, and its job is to measure the position, distance, and motion of nearly two billion stars.

👉 See also: Margaret Hamilton Net Worth: The Real Story Behind the Software Legend

Two billion sounds like a lot. It’s less than 1% of the galaxy.

But even that 1% changed everything. Gaia data showed us that the Milky Way isn't a flat, static plate. It’s warped. It wobbles. Think of a spinning pizza crust that's been sat on by a toddler. The outer edges of the galaxy are flared and twisted, likely because of past collisions with smaller dwarf galaxies like Sagittarius. When you look at a modern, data-driven map, you aren't seeing a peaceful celestial suburb. You’re seeing a crime scene of galactic cannibalism.

Why We Keep "Losing" the Spiral Arms

If you ask a kid to draw the Milky Way, they’ll draw four big arms. Ask a scientist, and you'll get a sigh.

For a long time, the consensus was that we had four major spiral arms: Perseus, Scutum-Centaurus, Sagittarius, and Norma. But then the Spitzer Space Telescope came along and suggested that maybe two of those—Sagittarius and Norma—are actually just minor branches or "spurs" of gas and dust rather than full-blown arms. It’s honestly embarrassing that we still argue about this.

We’re stuck in the Local Arm, or the Orion Spur. For a long time, we thought our home was just a tiny bridge between the bigger Perseus and Sagittarius arms. Recent mapping suggests the Orion Spur is way more substantial than we thought. It might even be a significant branch in its own right. This matters because where you are in the map determines what you see in the night sky. If we were tucked deep inside a dense arm, our sky would be so bright with star-forming gas that we might never have seen the distant universe.

The Great Galactic Bar

Most people think the center of the Milky Way is a circle. It isn't. It’s a bar.

This is a massive, rectangular-ish structure of old, red stars that stretches across the center. It’s about 27,000 light-years long. This bar acts like a giant celestial blender. It stirs up gas and funnels it toward the central supermassive black hole, Sagittarius A*. If you look at a map of the Milky Way from a "top-down" perspective, that bar is the engine driving the whole show. It creates the gravitational resonance that keeps the spiral arms from just flying apart or winding up into a tight ball.

The Dust Problem

The biggest headache in mapping our home is dust. Not the stuff under your bed, but microscopic grains of carbon and silicates. This soot blocks visible light. When you look toward the center of the galaxy in the summer sky, you see dark patches. Those aren't empty space; those are "Great Rifts" of dust blocking the light of billions of stars behind them.

✨ Don't miss: APES Unit 7 FRQ: Why Atmospheric Pollution Still Trips Everyone Up

To get around this, we use radio astronomy. Hydrogen gas—the most common stuff in the universe—emits a specific radio signal at a wavelength of 21 centimeters. Radio waves don't care about dust. They sail right through it. By tracking the "redshift" and "blueshift" of this hydrogen signal (how the frequency changes as things move toward or away from us), we can calculate how fast different parts of the galaxy are rotating. This is how we mapped the "far side" of the Milky Way, a place we will never actually see with our eyes.

Recent Discoveries That Broke the Map

In 2020, researchers at Harvard discovered something called the Radcliffe Wave. It’s a massive, 9,000-light-year-long "wave" of star-forming filaments in the solar neighborhood. It’s the largest coherent structure we’ve ever seen in our corner of the galaxy.

The crazy part? It was hiding in plain sight.

Before we had the precision of the Gaia data, we thought these clouds of gas were part of a ring called Gould’s Belt. Nope. They are part of a giant, undulating wave that rises 500 light-years above and below the galactic plane. This discovery fundamentally changed the map of the Milky Way near Earth. It proved that even in our own "backyard," we are still finding massive structures that we completely missed for centuries.

Then there are the Fermi Bubbles. These aren't stars or gas, but two gargantuan lobes of high-energy gamma radiation blowing out from the center of the galaxy. They extend for 25,000 light-years above and below the disk. Imagine a burger where the meat is the galaxy and the buns are invisible, radioactive balloons. We didn't even know they existed until the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope spotted them in 2010. They are likely the "burp" from the last time our central black hole ate something big.

📖 Related: The Instagram Default Profile Picture: Why That Gray Silhouette Is Making a Comeback

How to Actually Use a Galactic Map

You can't use a map of the Milky Way to navigate like a GPS, at least not yet. But understanding it helps you realize our place in the "Galactic Habitable Zone."

If we were too close to the center, the radiation from supernovae and the density of stars would make life nearly impossible. Too far out, and there aren't enough heavy elements (like iron and gold) to form rocky planets. We are in the "Goldilocks" zone of the map. We’re in a quiet, stable suburb where the neighbors are spaced out just enough to keep things peaceful.

Practical Steps for Enthusiasts

If you want to move beyond looking at flat images and actually experience the 3D nature of the galaxy, there are a few things you should do:

- Download Gaia Sky: This is a real-time, 3D astronomy visualization software that uses the actual Gaia mission data. You can fly through the stars and see exactly how "clumpy" the galaxy really is.

- Look for the "Great Rift": Next time you’re in a dark sky area, look at the Milky Way. Find the dark lanes that seem to "split" the glowing band. You are looking at the dust clouds that make mapping so hard.

- Track the Perseus Arm: Using a basic star chart, find the Double Cluster in Perseus. When you look at it, you are looking specifically at a massive structure in the next spiral arm over from ours.

- Explore the Milky Way Project: This is a citizen science initiative through Zooniverse. You can help professional astronomers map "bubbles" and star-forming regions by looking at infrared images from the Spitzer Space Telescope. Humans are still better than AI at spotting certain patterns in cosmic dust.

The map of the Milky Way is a living document. It changes every time a new telescope goes up. We used to think we lived in a static, perfect spiral. Now we know we live in a warped, scarred, and vibrating collection of stars that is still reacting to collisions that happened billions of years ago. It’s a lot more chaotic than the posters in your 5th-grade classroom, and honestly, that makes it way more interesting.

The next big update will likely come from the Vera C. Rubin Observatory. Once that starts its ten-year survey of the sky, we’re going to find even more "invisible" structures, dark matter filaments, and rogue stars that shouldn't be where they are. Mapping a galaxy is a slow-motion project that will take centuries to finish. We’re just lucky enough to be alive while the first accurate drafts are being drawn.