If you want to understand why the headlines out of Damascus, Baghdad, or Jerusalem look the way they do today, you basically have to look at a single, messy year. 1920. That’s the year the modern world was forced onto a region that wasn't really asked if it wanted it. When you look at a map of the Middle East in 1920, you aren't just looking at geography. You’re looking at a crime scene, a blueprint, and a massive geopolitical gamble that we are all still paying for.

It was chaotic.

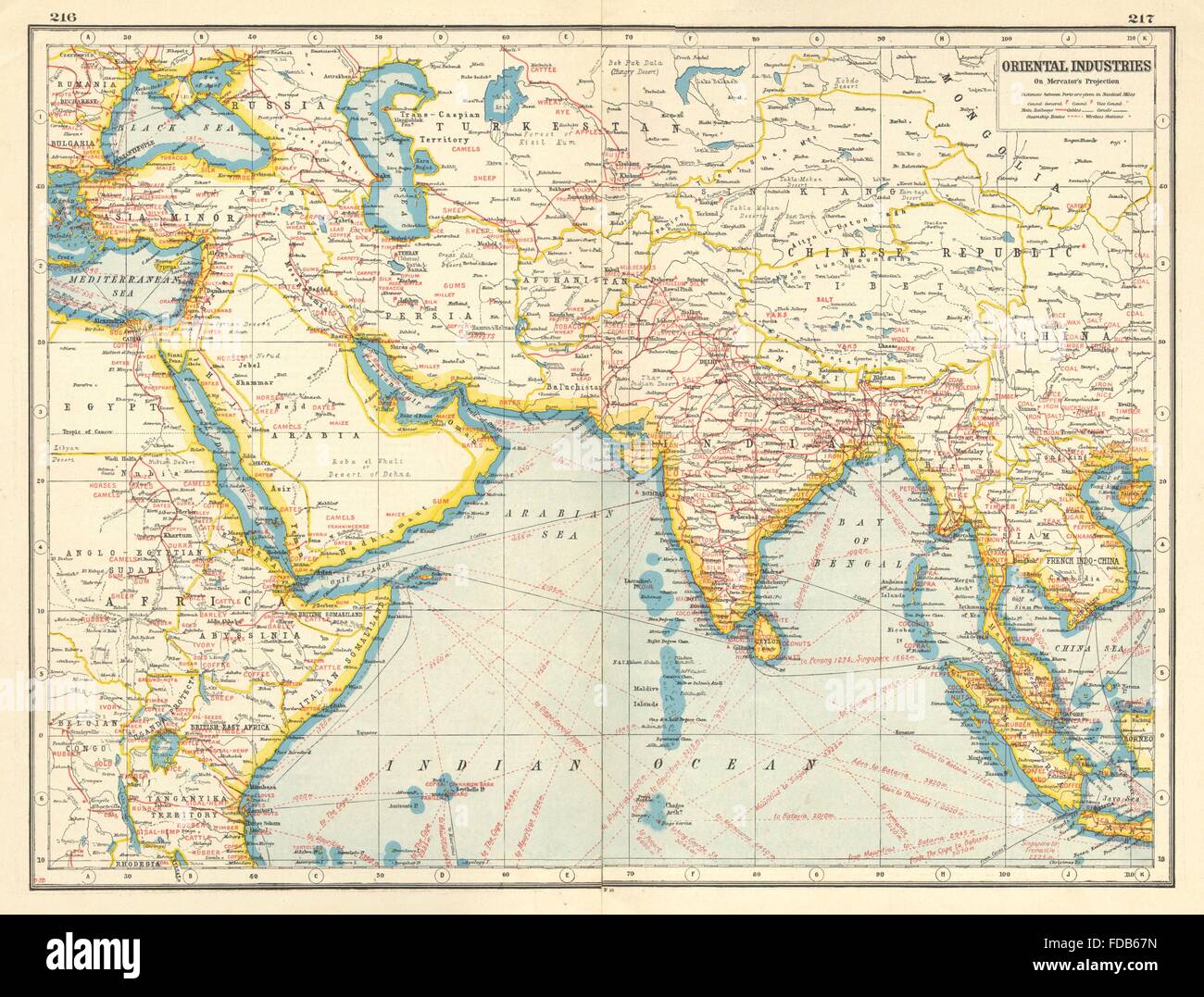

The Ottoman Empire, which had run the show for centuries, was dead. It was a corpse being picked over by British and French diplomats who were more interested in oil and shipping lanes than the people actually living on the ground. They sat in rooms in San Remo and London, drawing lines with rulers. Seriously. If you’ve ever wondered why some borders in the desert are perfectly straight, it’s because a guy named Mark Sykes or Georges Picot decided that’s where his pencil should stop.

The San Remo Conference and the Death of Dreams

Everything changed in April 1920. That was the San Remo Conference.

Before this, there was this hope—this really intense, almost desperate hope—among Arab leaders that they’d get their own independent kingdom. They’d fought alongside the British against the Turks. They’d been promised sovereignty. T.E. Lawrence (yes, Lawrence of Arabia) had been part of those whispers. But by the time the map of the Middle East in 1920 was finalized at San Remo, those promises were basically trash.

The British took "mandates" (which is just a polite 1920s word for colonies) over Palestine and Mesopotamia, which we now call Iraq. The French grabbed Syria and Lebanon.

The locals were furious. King Faisal, who had been declared King of Greater Syria just weeks earlier, suddenly found out his kingdom didn't exist in the eyes of Europe. He had a throne but no map. By July, French tanks were rolling into Damascus. The Battle of Maysalun happened. It was a slaughter. A small, brave Syrian force tried to stop a professional European army. They lost, Faisal was kicked out, and the French solidified their grip.

Iraq: A Country Made by Force

Look at the right side of that 1920 map. You’ll see Mesopotamia.

💡 You might also like: Why a Man Hits Girl for Bullying Incidents Go Viral and What They Reveal About Our Breaking Point

The British decided to take three very different Ottoman provinces—Baghdad, Basra, and Mosul—and smash them together into one country. They called it Iraq. It sounds simple on paper. In reality, it was a disaster from day one. You had Sunnis, Shias, and Kurds all suddenly told they were one "nation" under British supervision.

It didn't go well.

By the summer of 1920, Iraq was in a full-blown revolt. It was huge. Thousands of people died. The British were shocked. They’d just finished World War I and were broke, and suddenly they were spending millions of pounds trying to suppress a rebellion in a place they barely understood. They eventually flew Faisal in—the guy the French just kicked out of Syria—and made him King of Iraq as a sort of "sorry about that" gesture.

It was a "nation-building" project 100 years before that term became a buzzword. And it was just as messy then as it is now.

The Mandate for Palestine and the Balfour Ghost

The map of the Middle East in 1920 also marks the moment the British Mandate for Palestine became official. This is where things get really complicated.

The British were trying to balance two things that were fundamentally unbalanceable. They had the Balfour Declaration from 1917, which promised a "national home for the Jewish people." But they also had a massive Arab population that had lived there for generations and had no intention of leaving or being ruled by someone else.

In 1920, the first major riots broke out in Jerusalem. The Nebi Musa riots. It was a sign of the next century of conflict. When you look at the borders drawn in 1920, you see the physical container for a struggle that hasn't stopped for a single day since. The British thought they could manage it. They couldn't.

📖 Related: Why are US flags at half staff today and who actually makes that call?

Why the Lines Look So Weird

People always talk about "lines in the sand."

The reason the map of the Middle East in 1920 looks so geometric is that the European powers didn't care about tribal lands, water rights, or ethnic groupings. They cared about the railway from Kirkuk to Haifa. They cared about who controlled the Suez Canal.

Take the "Hickory’s Trunk" or "Winston’s Hiccup"—that weird jagged line in the border of Jordan. Legend has it Churchill drew it after a particularly boozy lunch. While that might be a bit of an urban legend, the truth isn't much better. The borders were drawn to satisfy European egos and oil company balance sheets.

The French Influence in the Levant

The French were obsessed with protecting Christian populations in the East. That’s why they carved Lebanon out of Syria. They wanted a Maronite-led state that would be an ally to Paris. In doing so, they planted the seeds for the Lebanese Civil War decades later because they created a state with a very fragile demographic balance.

Syria, meanwhile, was chopped up into tiny "states" by the French—an Alawite state, a Druze state, the State of Aleppo. They tried to "divide and rule." It didn't work long-term, but it left a legacy of deep suspicion toward central government that still haunts the region.

The Turkey Exception

The one place where the 1920 map actually got pushed back was Turkey.

The original plan (the Treaty of Sèvres) was to carve Turkey up like a Thanksgiving turkey. The Greeks were going to get a huge chunk. The Italians and French wanted pieces. The Armenians and Kurds were promised independent states.

👉 See also: Elecciones en Honduras 2025: ¿Quién va ganando realmente según los últimos datos?

But Mustafa Kemal Atatürk said no.

He led a war of independence that basically tore up the 1920 European map for Anatolia. It’s the only part of the Middle East where the local population successfully fought off the "map-makers" of San Remo. This is why Turkey’s borders look "natural" compared to the straight lines of Jordan or Iraq. They were won on the battlefield, not drawn in a French villa.

What This Means for You Right Now

You can't look at modern Lebanon's economic collapse or the Syrian civil war without seeing the ghost of 1920.

When borders are artificial, the only way to keep a country together is often through a "strongman" leader. That’s why the 20th century in the Middle East was defined by kings and dictators. They were trying to hold together "nations" that were created by British and French bureaucrats 100 years ago.

It’s also why groups like ISIS, back in 2014, literally filmed themselves bulldozing the border between Iraq and Syria. They called it "The End of Sykes-Picot." They knew that for many people in the region, those 1920 borders represent a century of humiliation and foreign interference.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs and Travelers

If you're trying to wrap your head around this, don't just look at a modern map. You have to compare.

- Overlay the Maps: Get a copy of the 1914 Ottoman administrative map and put it next to the map of the Middle East in 1920. You’ll see how "Syria" used to include what is now Israel, Palestine, Jordan, and Lebanon.

- Read the Primary Sources: Look up the King-Crane Commission report. It was a 1919 American study where they actually asked people in the Middle East what they wanted. The results? They wanted independence and definitely didn't want the French. The British and French ignored the report entirely. Reading it today is heartbreaking because it predicted exactly what would go wrong.

- Follow the Oil: Trace the Iraq Petroleum Company’s early pipelines. You will notice the borders of 1920 often follow the proposed path of those pipes.

The 1920 map isn't "just history." It’s the framework of our current world. The tensions in Gaza, the instability in Beirut, and the power struggles in Baghdad are all chapters in a book that was started by men in suits a century ago who thought they could reshape the world with a pen.

Next time you see a straight line on a map of the desert, remember it’s not just a border. It’s a scar.

To really get the full picture, look into the 1921 Cairo Conference. That's where Winston Churchill and his "40 Thieves" (his team of advisors) tried to fix the mess they made in 1920. It didn't work, but it explains why the British royal family ended up on thrones in Jordan and Iraq. Looking at that conference is the logical next step in understanding how the map we see today was finalized.