Hyrule is a grid. 128 screens of pure, unadulterated chaos. Honestly, if you grew up in 1987, the map of The Legend of Zelda NES wasn't just a game feature; it was a physical artifact, usually a piece of graph paper stained with soda and covered in frantic pencil marks. There was no in-game GPS. No mini-map in the corner of your CRT television. You had a grey rectangle and a tiny blinking dot. That was it.

It’s easy to forget how radical that felt. Before Zelda, most games pushed you to the right. Mario went right. Mega Man went right. Link? Link could go anywhere, and he usually ended up dead in the woods because you took a wrong turn at a bush that looked exactly like every other bush. The Overworld was a massive $16 \times 8$ grid, and navigating it required a level of spatial awareness that most eight-year-olds simply didn't possess yet.

The Secret Geometry of Hyrule

The map of The Legend of Zelda NES is structured with a mathematical rigidity that contradicts its whimsical fantasy setting. The entire Overworld is built on a coordinate system. Most veteran players refer to the starting screen as 7-H or something similar, depending on which fan-made atlas they’re using.

Everything is deliberate. Shigeru Miyamoto famously wanted to recreate the feeling of exploring the woods behind his childhood home in Kyoto. He wanted players to feel lost. He succeeded. You’ve got the Lost Woods in the southwest—a screen that loops infinitely unless you know the "Up, Left, Down, Left" sequence—and the Lost Hills in the north that pull the same trick.

But here’s the thing: the map is actually incredibly small by modern standards. It’s tiny. If you ran from the bottom-left corner to the top-right without stopping, it would take you maybe two minutes. Yet, it feels infinite because of how the developers used verticality and barriers. You see a Heart Container on a pier, but you can't reach it. You see a doorway across a river, but you don't have the raft. The map is a series of locks, and the items are the keys. It’s a masterpiece of gated exploration.

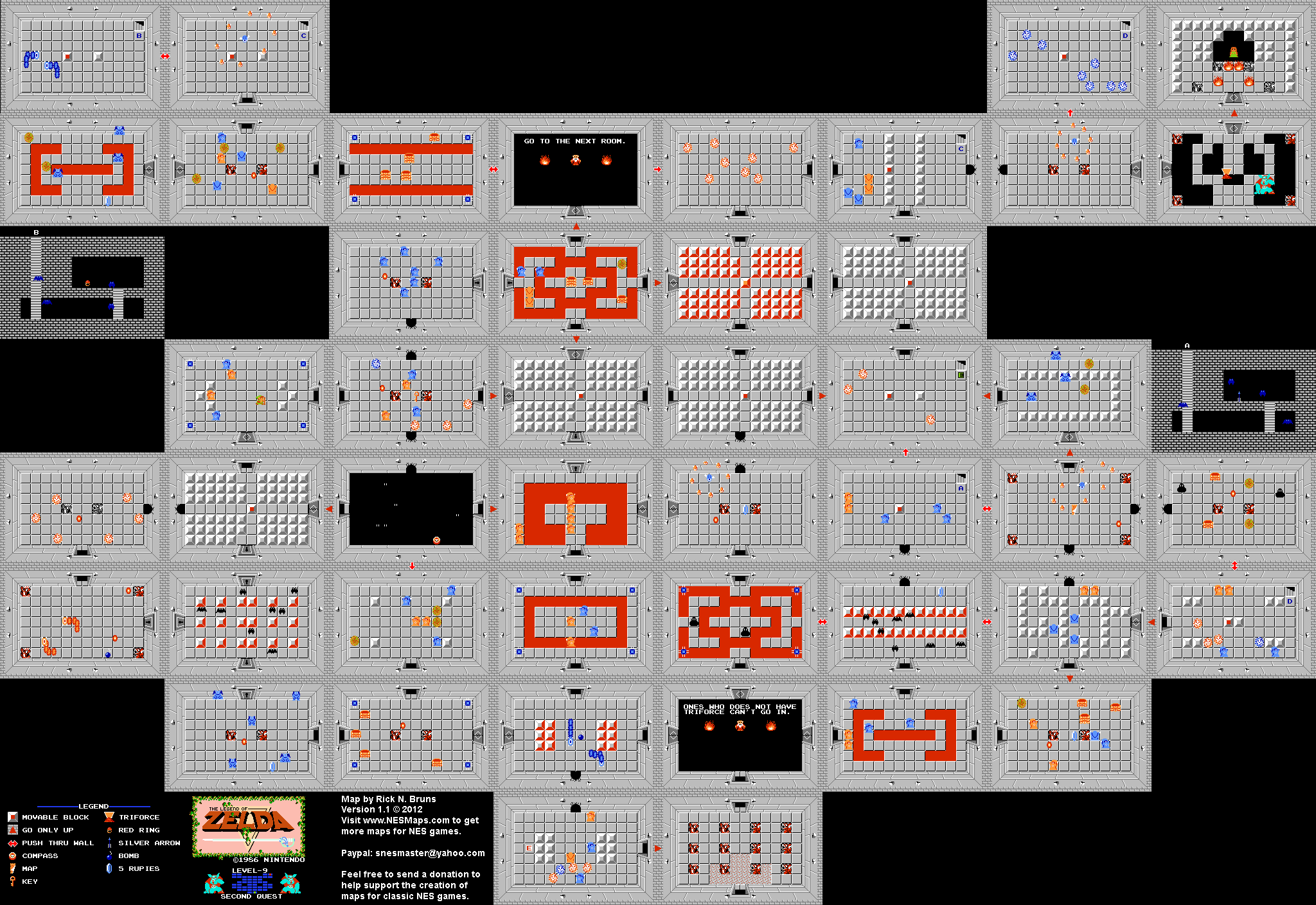

Why the "Second Quest" Map Changes Everything

Once you beat Ganon, or if you're a cheater who named their save file "ZELDA," the game flips the script. The Second Quest doesn't just make enemies harder; it reconfigures the logic of the map of The Legend of Zelda NES.

📖 Related: Is the PlayStation 5 Slim Console Digital Edition Actually Worth It?

Suddenly, you’re walking through walls. Literally.

In the First Quest, walls were boundaries. In the Second Quest, walls are suggestions. This was a psychological masterstroke. Nintendo knew you had memorized the layout, so they rewarded that familiarity by subverting it. Level 4 isn't where it used to be. The Power Bracelet is in a different spot. It forced players to re-map their mental image of Hyrule, effectively doubling the game's longevity without adding a single pixel of new landscape.

The Physicality of 1980s Navigation

We have to talk about the physical map that came in the box. It was a fold-out beauty, but it was incomplete. Nintendo intentionally left "blank" spots on the printed map. They wanted you to fill them in. They wanted you to feel like a cartographer.

This created a community of shared knowledge. You heard a rumor at school that if you burned a specific bush on a specific screen, you’d find a shop. You went home, tried it, and it worked. That feeling of "uncovering" the map of The Legend of Zelda NES is something modern games struggle to replicate with their "tower-climb-to-reveal-icons" mechanics. In Zelda, the icon was the secret, and the secret was everywhere.

The Specter of the "Death Mountain" Ascent

The top of the map is a jagged, brown mess of rocks and frustration. This is where the difficulty spikes. To get to Level 9, you have to find two specific rocks to bomb. There are no visual cues. None. You just have to be curious (or desperate) enough to start blowing things up.

👉 See also: How to Solve 6x6 Rubik's Cube Without Losing Your Mind

- The Graveyard: Six screens of ghosts (Ghini) that spawn if you touch the headstones.

- The Coast: Where you find the White Sword if you have enough heart containers.

- The Desert: Home of the Leevers and the entrance to Level 6.

Each "biome" on the map has a distinct personality despite the limited NES color palette. The woods are green and claustrophobic. The mountains are brown and vertical. The lakes are blue and... well, mostly full of Zoras trying to kill you.

Accuracy and Misconceptions

People often think the map of The Legend of Zelda NES is randomized. It isn't. Not even a little bit. Every single bush that can be burned and every rock that can be bombed is hard-coded into the ROM. There are exactly 128 screens in the Overworld, and 128 screens in the Underworld (the dungeons).

Another common myth is that you need the manual to find the dungeons. While it helps, the game actually gives you "hints" via the Old Men in caves. "Secret is in the tree at the dead end." "Amesia is the way to the mountain." Okay, the translations were terrible (thanks, 1980s localization teams), but the intent was there. The map was a puzzle to be solved, not just a place to exist.

Navigating the Underworld

The dungeons themselves are shaped like objects. This is a detail many people missed until they started drawing their own maps.

- The Eagle

- The Moon

- The Manji (a traditional Buddhist symbol, often confused for something else in the West)

- The Snake

- The Lizard

- The Dragon

- The Demon

- The Lion

- Death Mountain (shaped like a skull)

This wasn't just flavor text. The shape of the map of The Legend of Zelda NES dungeons often dictated the flow of the rooms. If you were in the "tail" of the Snake, you knew you had a long walk to the "head."

✨ Don't miss: How Orc Names in Skyrim Actually Work: It's All About the Bloodline

Actionable Tips for Modern Cartographers

If you are playing this on the Switch Online service or a classic NES today, don't use a guide immediately. You’ll rob yourself of the core experience. Instead, try these steps to master the map naturally:

The Rule of the Red Candle: Once you get the Red Candle from Level 7, burn every single bush. It sounds tedious, but the NES map is small enough that you can sweep the whole thing in twenty minutes. You will find more "Secret is a Money to Everyone" caves than you ever thought possible.

Counting Screens: Use the "starting screen" as 0,0. When you find something cool, write down how many screens North and East it is. This is how speedrunners like LackAttack or Kosmic keep their bearings during high-pressure runs.

Visual Landmarks: Look for "anomalies." If there is a single green bush in a field of brown ones, burn it. If there is a rock that isn't connected to the cliffside, bomb it. The developers weren't mean; they were subtle.

Respect the Boundaries: The edges of the map aren't just invisible walls; they are often the most lucrative areas. The "Top Right" corner of the map holds one of the most important shops in the game, but most people never wander that far because the enemies there (Blue Lynels) are terrifying. Go anyway.

The map of The Legend of Zelda NES is a masterclass in minimalist design. It proves that you don't need 4K textures or a 50-mile draw distance to create a sense of scale. You just need a sense of mystery and a few well-placed secrets. Even forty years later, players are still finding new ways to sequence-break this grid, proving that while the map may be static, our understanding of it is always evolving.

To truly master Hyrule, stop looking at your phone and start looking at the screen. Pay attention to the patterns of the tiles. Notice where the Zora's bubbles don't appear—that's often where a hidden path lies. The map is talking to you; you just have to learn the language.