Manhattan is a rectangle. Or at least, that’s what your brain wants to believe when you look at a modern map of the island of Manhattan. You see those clean, perpendicular lines of the 1811 Grid Plan and you think, "Okay, I get it." But Manhattan is actually a lie. Well, maybe not a lie, but it's a massive, ongoing terraforming project that has been stretching, bloating, and flattening itself for four hundred years. If you compared a map from the 1600s to a GPS readout today, you’d realize that a huge chunk of the "land" you’re walking on—especially in Battery Park City or the FDR Drive—is actually just colonial trash, subway dirt, and sunken ships.

It's weird.

We treat the map like a fixed document, but in New York, the geography is more of a suggestion.

The Grid That Ate the Hills

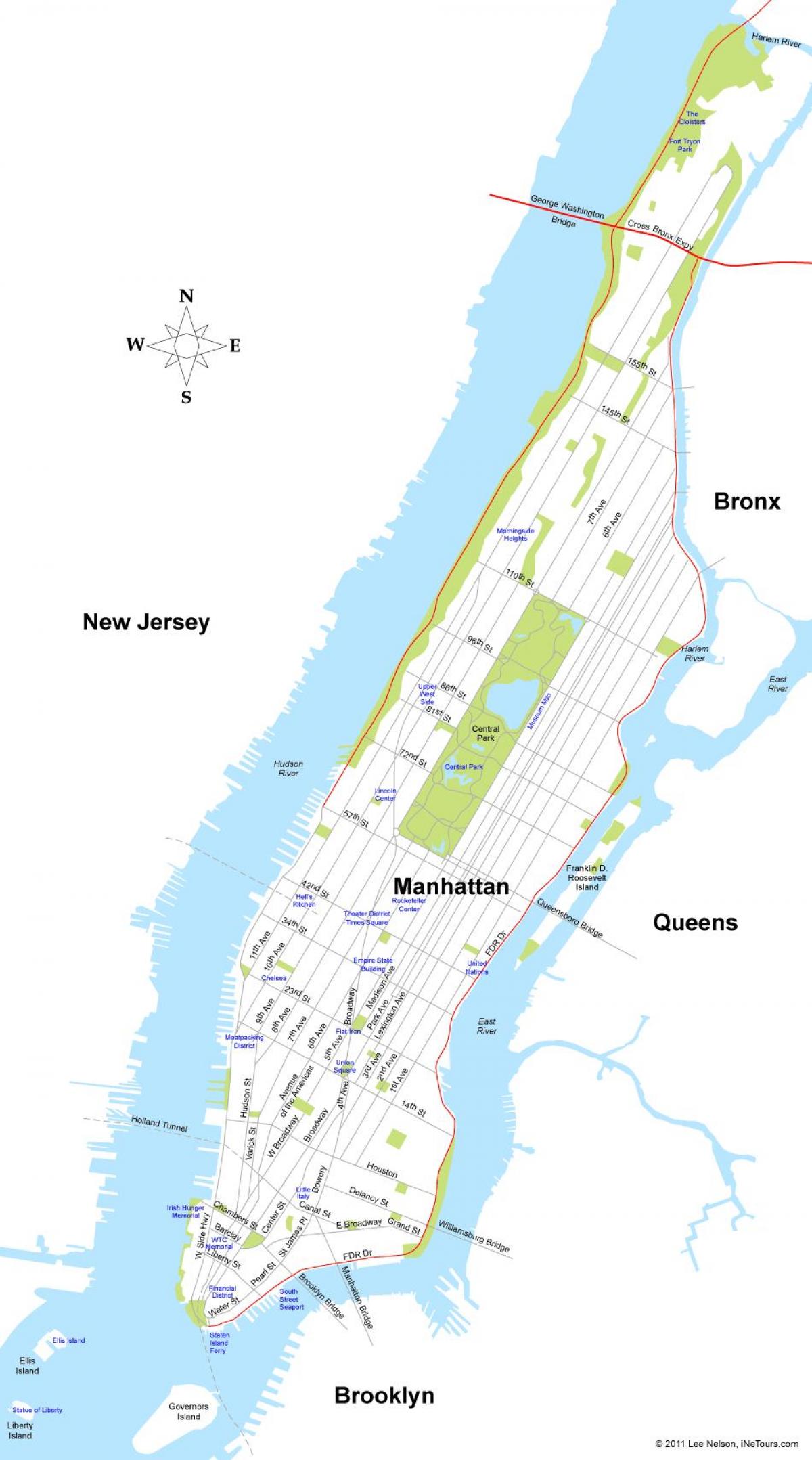

Most people looking for a map of the island of Manhattan are looking for the grid. You know the one. 5th Avenue splits the East and West sides, the numbers go up as you head North, and you basically can't get lost unless you’re below Houston Street. But before the Commissioners' Plan of 1811, Manhattan was a topographical nightmare of swamps, massive rocky outcrops, and actual mountains.

There was a hill called Mount Bayard near what is now Grand Street. It was the highest point in the lower island. The city just... deleted it. They flattened it to fill in the Collect Pond, which was a 70-acre body of water that became so polluted by slaughterhouses that it turned into a literal biohazard. When you look at a map today, you see "Canal Street." That isn't just a name. It was an actual canal built to drain that toxic pond.

The 1811 grid was brutalist before brutalism was a thing. It ignored the terrain. If a hill was in the way of 42nd Street, the hill was leveled. If a valley existed, it was filled with the rubble of the hill. The only reason Central Park looks "natural" on your map is that Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux spent years blowing up rocks with more gunpowder than was used at the Battle of Gettysburg to make it look like a "wilderness."

🔗 Read more: Finding Alta West Virginia: Why This Greenbrier County Spot Keeps People Coming Back

The Moving Shorelines

If you’re standing on the corner of Pearl Street and Wall Street, you’d assume you’re safely inland. You aren't. In the 1700s, Pearl Street was the shoreline. It’s called "Pearl" because of the oyster shells found there.

Every time you look at a map of the island of Manhattan, you have to account for the "made land." This isn't just a historical footnote; it’s about 25% of the island's current footprint. Battery Park City is the most famous example. In the 1970s, when they were digging out the foundation for the original World Trade Center, they had a problem: what do you do with 1.2 million cubic yards of dirt and rock?

They dumped it in the Hudson.

They created 92 acres of new country. They literally moved the map westward. When you look at the jagged edges of the West Side Highway today, you’re looking at a man-made boundary that the Lenape people wouldn't recognize.

The Mapping of Subterranean Manhattan

A map of the surface is only half the story. Honestly, the most interesting map of the island of Manhattan is the one you can't see. Below the asphalt is a spaghetti-mess of infrastructure that shouldn't work, but somehow does.

💡 You might also like: The Gwen Luxury Hotel Chicago: What Most People Get Wrong About This Art Deco Icon

- The Water Tunnels: There are massive tunnels, like City Water Tunnel No. 3, which has been under construction since 1970. It’s hundreds of feet below the bedrock.

- The Pneumatic Tubes: Back in the day, the USPS used to fire mail through pressurized tubes under the streets at 30 miles per hour.

- The Steam System: New York has the largest district steam system in the world. Those orange-and-white striped chimneys you see on the street? They’re venting pressure from a network that keeps the Empire State Building warm.

Mapping this is a nightmare. Every time a utility company digs a hole, they find something they didn't know was there. Old wooden water pipes from the Manhattan Company (founded by Aaron Burr, by the way) are still occasionally found under the streets of Lower Manhattan. Think about that: we are using 21st-century satellites to map a city built on top of 18th-century wood.

Why the "North" on Your Map is Wrong

Here’s something that bugs cartographers: Manhattan North isn't North.

If you follow a map of the island of Manhattan and walk "Uptown," you aren't walking toward the North Pole. You’re walking about 29 degrees east of true north. The island is tilted. This quirk is what gives us "Manhattanhenge." Twice a year, the sun aligns perfectly with the east-west streets because the grid is offset from the actual cardinal directions.

If the city had been built on a true North-South axis, the sunsets would be different, the wind tunnels between skyscrapers would shift, and the "canyons" of Wall Street would have entirely different lighting patterns.

Navigating the Map: Practical Realities

When you’re actually using a map of the island of Manhattan to get around, you have to ignore the scale sometimes. Broadway is the Great Rule Breaker. It’s the old Wickquasgeck Trail, an indigenous path that follows the high ground of the island. It refuses to obey the grid. It slices diagonally through the city, creating "squares" wherever it hits an Avenue—Union Square, Madison Square, Herald Square, Times Square.

📖 Related: What Time in South Korea: Why the Peninsula Stays Nine Hours Ahead

If you are trying to be efficient:

- Trust the Grid, but respect the "Way." Broadway is usually the fastest way to walk diagonally, but the most confusing way to give directions.

- The "H" System. Manhattan is basically three long corridors. The West Side (12th to 8th Aves), the Center (7th to 5th Aves), and the East Side (Park to York). Switching between them takes longer than traveling 20 blocks North-South.

- The Subway Map is a Diagram, Not a Map. This is the biggest mistake tourists make. The official MTA map distorts the size of the island to make the subway lines readable. If you think two stations look close on the MTA map, they might be a 15-minute walk apart in real life.

The Future Map: Climate and Sinking

We have to talk about the "Blue Line." If you look at current topographical maps, Manhattan is surprisingly low-lying. The "map" is going to change again, but this time it might not be our choice.

The "Big U" is a proposed plan—parts of it are already happening—to create a massive system of berms and parks around the southern tip of the island to prevent another Hurricane Sandy disaster. This will, once again, change the map of the island of Manhattan. We are thickening the "skin" of the island to protect it from the rising harbor.

Mapping Manhattan isn't about drawing a shape. It’s about documenting a living organism that eats its own history to grow bigger.

Actionable Insights for Using the Manhattan Map

- Use OpenStreetMap for Pedestrian Detail: While Google Maps is great for traffic, OpenStreetMap often has better data on building entrances and "privately owned public spaces" (POPS) where you can sit and eat lunch.

- Download the "Manhattan Past" Overlays: If you're a history nerd, use tools like the NYPL’s Map Warper. You can overlay a 19th-century map over your current GPS location and see exactly what used to be where you're standing. Usually, it was a brewery or a stable.

- Learn the Address Formula: To find the nearest cross street for an avenue address, there’s an old "Manhattan Address Algorithm." For example, for 5th Avenue, you divide the house number by 20 and add 18. It’s weirdly accurate.

- Observe the "Street Wall": When looking at a map of Midtown, notice the density. The map doesn't show you the wind. Because of the grid and the height of the buildings, the "map" of wind speed in Manhattan is one of the most complex in the world. Avoid 23rd street near the Flatiron on a windy day; the "Downdraft Effect" is real and it will ruin your umbrella.

Manhattan is a stubborn piece of rock. It’s been carved, blasted, and extended, but the underlying schist—the hard bedrock that allows for skyscrapers—is what really dictates the map. Whether you’re looking at it on a screen or a folded piece of paper, you’re looking at a 400-year-old construction site.