If you’ve ever stood on the cliffs at Pointe du Hoc, you realize something pretty fast. The maps we see in history books—those clean, colored arrows sweeping across a blue English Channel—are kind of a lie. Or, at least, they’re a massive oversimplification of a chaotic, bloody mess. Looking at a map of the invasion of Normandy today feels like looking at a blueprint for the impossible. It wasn’t just a "landing." It was the largest seaborne invasion in history, and the geography of the French coastline almost made it a failure.

History is messy.

In June 1944, the Allied forces weren't just fighting Germans; they were fighting the moon, the tide, and some of the most unforgiving sand on the planet. When you look at the tactical overlays from Operation Overlord, you’re seeing years of deception and months of agonizing math. They had to find a place where the gradients were shallow enough for Higgins boats but the exits weren't complete death traps.

The Five Beaches and the Geography of Chaos

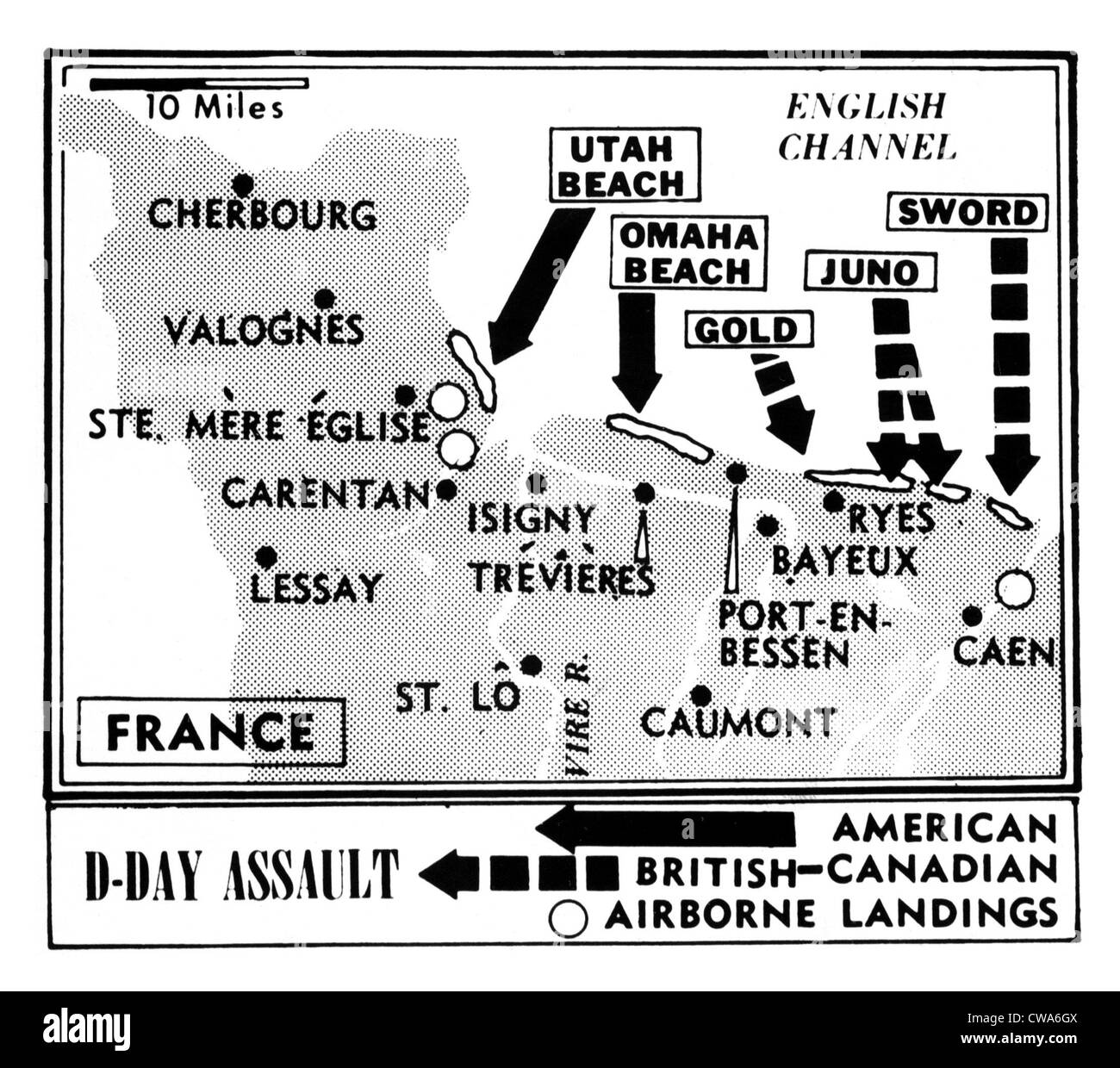

The maps basically split the 50-mile stretch of the Calvados coast into five sectors. You’ve got Utah and Omaha for the Americans, and Gold, Juno, and Sword for the British and Canadians. But looking at the sector lines doesn't tell you about the "shingle." At Omaha, there’s this steep bank of smooth stones. Imagine trying to run up a pile of marbles while someone is firing a Maschinengewehr 42 at you from a concrete bunker.

Utah Beach was actually a bit of an accident.

Strong currents pushed the U.S. 4th Infantry Division about 2,000 yards south of their intended target. Brigadier General Theodore Roosevelt Jr. realized the error, looked around, and famously decided they’d "start the war from right here." The map changed in real-time. Because they landed in a less defended spot, their casualties were significantly lower than at Omaha.

Omaha was the nightmare. The maps showed "draws"—five natural valleys that led off the beach and into the bluffs. The plan was to use these to get vehicles inland. Instead, the Germans had turned every single draw into a pre-registered kill zone. If you look at the original BIGOT (Beyond Interdepartmental Government Overseas Territory) maps—which were so secret you’d be thrown in jail just for mentioning the name—you can see how much the Allies thought they knew about those defenses. They knew where the bunkers were, but they didn't know how well the 352nd Infantry Division would hold them.

💡 You might also like: Jersey City Shooting Today: What Really Happened on the Ground

Why the Map Looked the Way it Did

Why Normandy? Why not Pas-de-Calais?

If you look at a map of the English Channel, Calais is the obvious choice. It’s the shortest distance. The Germans knew this, too. They put the bulk of their 15th Army there. The Allies used a massive deception campaign called Operation Fortitude to keep them looking at Calais. They built fake tanks out of inflatable rubber and created a "ghost" army under George Patton.

The Normandy map was chosen because the beaches were sheltered from westerly winds by the Cotentin Peninsula. Also, the German defenses there—the Atlantic Wall—were slightly less dense than at the narrowest point of the Channel. It was a gamble on geography.

The Logistics Nobody Talks About

Most people focus on the arrows hitting the sand. But the most interesting part of the map of the invasion of Normandy is actually out at sea.

Specifically, the "Mulberry" harbors.

The Allies knew they couldn't capture a deep-water port like Cherbourg on day one. So, they decided to bring their own. They towed massive concrete caissons across the water and sank them to create artificial breakwaters. On the maps, these look like little geometric shapes sitting off the coast of Arromanches. In reality, they were a feat of engineering that allowed the Allies to land over 2 million men and 4 million tons of supplies.

📖 Related: Jeff Pike Bandidos MC: What Really Happened to the Texas Biker Boss

Then you have the paratroopers. The 82nd and 101st Airborne divisions were dropped inland to secure the bridges and "causeways"—narrow roads through flooded marshes. If you look at a topographical map of the area behind Utah Beach, it’s mostly swamps. The Germans had flooded the fields by damming the Merderet and Douve rivers. The map of the drop zones was a disaster. Pilots, flying through heavy cloud cover and anti-aircraft fire, scattered paratroopers miles from their targets. Men drowned in three feet of water because their gear was too heavy.

The Maps That Won the War

Mapping Normandy wasn't just about drawing lines. It was about "aquatic reconnaissance."

British frogmen actually swam to the beaches under the cover of darkness months before D-Day. They took core samples of the sand. Why? Because they needed to know if the beach could support the weight of a 30-ton Sherman tank. If the sand was too soft, the invasion would have literalized the phrase "stuck in the mud."

They also used "tourist maps." The BBC ran a campaign asking the British public for their vacation photos and postcards of the French coast. By looking at a family photo of a kid building a sandcastle in 1937, military intelligence could see the height of a sea wall or the position of a rock formation. These thousands of snapshots were stitched together into the most detailed invasion map ever conceived.

Misconceptions About the Front Lines

We often think of the invasion as a single line moving forward. It wasn't. It was a series of disconnected pockets.

For the first 24 hours, the map of the invasion of Normandy looked like a scatter plot. There were groups of soldiers from different units just trying to find each other in the hedgerows. These weren't the neat, manicured hedges you see in an English garden. They are "bocage"—ancient earthen mounds topped with tangled trees and thorns. They turned every field into a natural fortress.

👉 See also: January 6th Explained: Why This Date Still Defines American Politics

The German map was also a mess, but for different reasons. Their command structure was a nightmare of bureaucracy. Field Marshal Rommel was in Germany for his wife’s birthday. Hitler was asleep and his staff was too scared to wake him up to release the Panzer divisions. By the time the German tanks actually moved toward the "map" of the invasion, the Allies had already established a toehold.

Practical Ways to Use These Maps Today

If you're a history buff or planning a trip to France, don't just look at a static image on Wikipedia. To really understand what happened, you need to layer the information.

- Overlay Topography on Google Earth: Go to the Omaha Beach sector (Vierville-sur-Mer). Look at the elevation. When you see how steep those bluffs are, you realize the bravery required to run toward them.

- Study the BIGOT Maps: Many of these are now digitized and available through the National Archives or the Imperial War Museum. They show the incredible level of detail—down to individual pillboxes—the Allies had.

- Track the "Cut" lines: Look for the sunken lanes in the Normandy countryside. Many of these haven't changed since 1944. They explain why the breakout (Operation Cobra) took so long.

- Visit the Caen Memorial Museum: They have some of the best physical representations of the moving front lines during the Battle of Normandy.

The map of the invasion of Normandy isn't just a piece of paper. It’s a record of a moment when the entire world held its breath. It shows where the planning met the reality of the Atlantic wall, and where sheer human will overcame a geographical nightmare.

To truly grasp the scale, start by looking at the location of the "Cabbage Patch" near Sainte-Mère-Église. Then trace the path to the La Fière bridge. You'll see that the war wasn't won on the broad beaches alone; it was won in the tiny, muddy intersections of French farm roads that most maps don't even bother to name.

Immediate Next Steps for Researchers

To get a deeper, more accurate view of the invasion's geography, you should seek out the CMH (Center of Military History) "Green Books." Specifically, the volume Cross-Channel Attack contains the most authoritative tactical maps produced after the war.

You can also explore the National Collection of Aerial Photography (NCAP), which holds the actual reconnaissance photos taken by Spitfires and Mustangs in the weeks leading up to June 6. Comparing these "raw" photos to the finished invasion maps shows exactly how much guesswork was involved in the planning.

Finally, if you are visiting, use the "D-Day 80" apps often released by local French tourism boards. These use GPS to show you exactly where you are standing in relation to the historic troop movements, turning the entire landscape into a living map of the liberation.