It is massive. Honestly, you probably don't realize just how huge it is. When you look at a standard Mercator projection map of the countries of africa, the scale is almost always a lie. Greenland looks roughly the size of Africa on your old schoolroom wall, right? In reality, Africa is fourteen times larger. You could fit the United States, China, India, Japan, and most of Europe inside its borders and still have room for a few extra mid-sized nations.

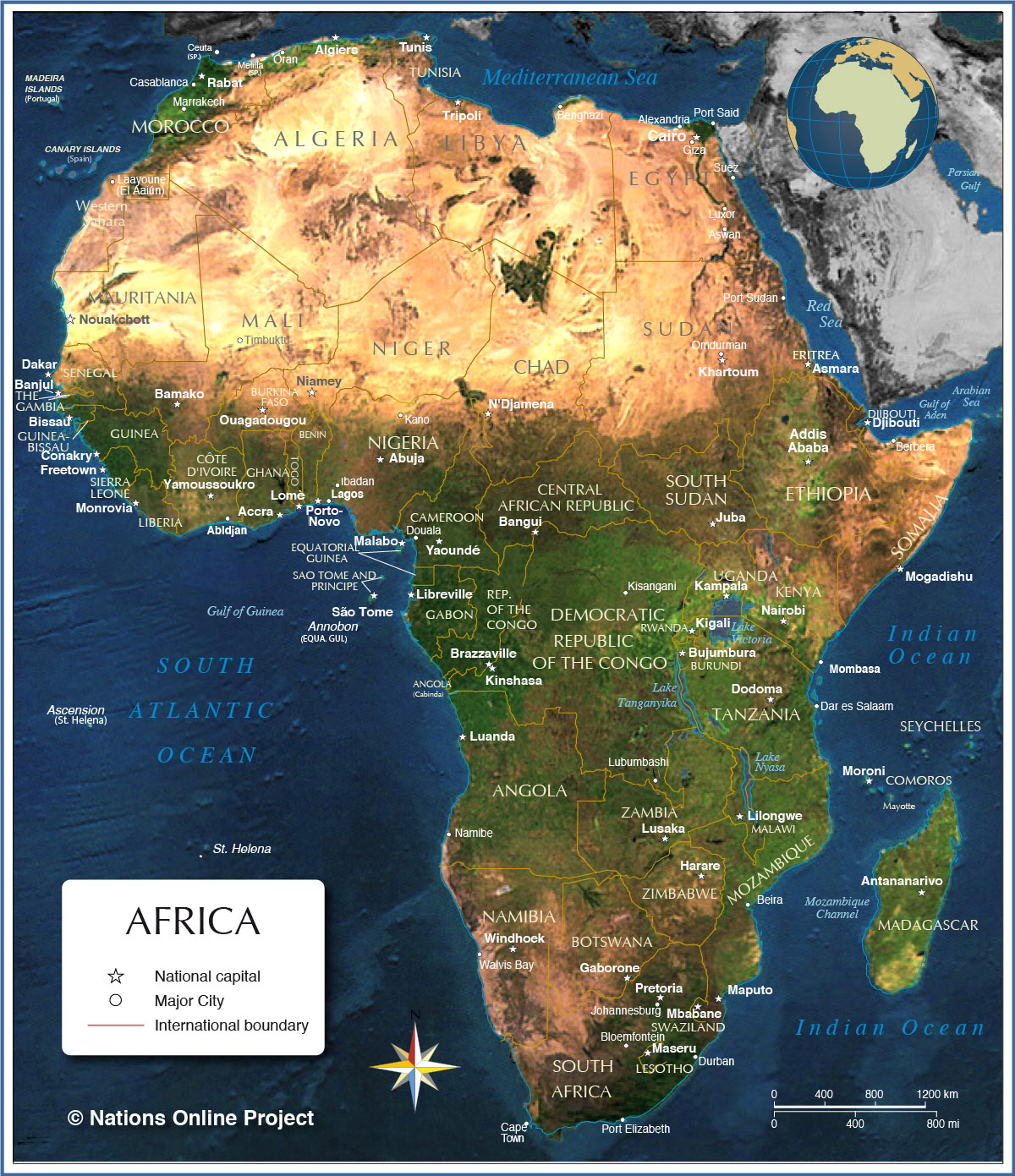

Most people see a monolith. They see "Africa" as a single entity rather than a complex puzzle of 54 distinct nations. Each of those borders tells a story—some are ancient, many are tragically arbitrary, and others are shifting as we speak.

If you're trying to navigate the continent or just understand the geopolitical landscape, you've got to stop looking at it as one big landmass. It’s a tapestry. A messy, vibrant, sometimes confusing tapestry.

The Mercator Problem and the True Scale of the Map

Geography is political. The maps we use most often, like the ones on Google Maps or in standard textbooks, use the Mercator projection. It was designed for 16th-century sailors to navigate the seas, not for accurate size comparison. Because it flattens a sphere into a rectangle, it stretches things near the poles and shrinks things near the equator. Since Africa sits right on the equator, it gets the short end of the stick.

Kai Krause, a renowned interface designer, famously created an infographic titled "The True Size of Africa." It went viral because it broke people's brains. Seeing the outline of the UK tucked into a tiny corner of Madagascar or realizing the entire contiguous US fits comfortably into just the Sahara and a bit of the Sahel changes how you think.

Size matters because it dictates everything from infrastructure costs to ethnic diversity. When you have a map of the countries of africa that covers 30 million square kilometers, you're dealing with vastly different climates, from the Mediterranean coast in the north to the temperate Cape in the south.

Colonial Ghosts and the Lines in the Sand

Why do so many borders in Africa look like they were drawn with a ruler? Because they were.

🔗 Read more: Entry Into Dominican Republic: What Most People Get Wrong

In 1884, a group of European leaders sat in a room in Berlin. They didn't have any Africans with them. They looked at a primitive map and started drawing lines to divide "spheres of influence." This is the "Scramble for Africa." They didn't care about the Zulu Kingdom, the Ashanti Empire, or the nomadic routes of the Tuareg. They cared about gold, rubber, and timber.

These "lines in the sand" are why some countries, like The Gambia, are essentially just a riverbank surrounded by another country. Or why the Caprivi Strip—that weird finger of land sticking out of Namibia—exists just because the Germans wanted access to the Zambezi River.

The Problem with Straight Lines

When you force different ethnic groups into one border or split a single tribe across three different countries, you get friction. Look at the Horn of Africa. The border between Ethiopia and Eritrea or the complex situation in Somalia stems directly from these colonial etchings. It’s not just "ancient tribal hatreds," as some lazy pundits claim. It’s a direct result of the map being drawn by people who never set foot on the soil they were dividing.

Northern Africa: More than Just the Sahara

The top of the map is dominated by the Maghreb and the Nile Valley. Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco. People often separate this region from "Sub-Saharan Africa," but that’s a bit of an oversimplification.

Algeria is the largest country on the continent by land area. It’s huge. Most of it is desert, but the northern coast is lush and Mediterranean. Then you have Egypt, which is essentially an oasis a thousand miles long. Without the Nile, the map of Egypt wouldn't exist; it would just be more empty desert.

The Sahel: The Great Buffer

Just below the Sahara lies the Sahel. It's a semi-arid belt stretching from Senegal in the west to Djibouti in the east. It’s a transition zone. Countries like Mali, Niger, Chad, and Sudan sit here. This is where the map gets tricky. Climate change is pushing the desert south, which means these borders are under constant pressure from resource scarcity.

💡 You might also like: Novotel Perth Adelaide Terrace: What Most People Get Wrong

West Africa: The Powerhouse of Diversity

If you look at the "bulge" of the map of the countries of africa, you’re looking at West Africa. This is where the density starts to pick up. Nigeria is the big player here. It's the most populous country on the continent. By 2050, it might even overtake the United States in population.

But look closer at the map. You have tiny nations like Togo and Benin sandwiched between giants. This area was the heart of the ancient Ghana, Mali, and Songhai Empires. Today, it’s a hub of economic growth, but the borders are still a logistical nightmare for trade. Imagine trying to drive a truck from Lagos to Abidjan. You’re crossing multiple borders, dealing with different currencies, and navigating roads that the map says are highways but are actually mud tracks in the rainy season.

Central Africa: The Green Heart

The middle of the map is dominated by the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). It is the size of Western Europe. It is incredibly rich in minerals like cobalt and coltan—the stuff in your smartphone—but it’s also one of the hardest places to map accurately.

The Congo Basin is the world's second-largest rainforest. Logistics here are almost impossible. There are very few paved roads connecting the east to the west. In many ways, the "map" of the DRC is more about the river systems than the roads.

Landlocked Struggles

Check out the countries like Rwanda, Burundi, and the Central African Republic. Being landlocked on a continent this big is a massive disadvantage. You’re at the mercy of your neighbors’ ports. If Kenya or Tanzania has a strike or a political upheaval, countries hundreds of miles inland feel the squeeze immediately.

East Africa and the Great Rift

This is where the map is literally tearing apart. The East African Rift is a tectonic plate boundary that runs from the Red Sea down through Mozambique. It’s created some of the most dramatic geography on the planet: the Ethiopian Highlands, Mount Kilimanjaro, and the Great Lakes (Victoria, Tanganyika, Malawi).

📖 Related: Magnolia Fort Worth Texas: Why This Street Still Defines the Near Southside

- Ethiopia: Never colonized (except for a brief Italian occupation). Its borders are more organic than many of its neighbors.

- Kenya and Tanzania: The giants of the region, competing for dominance in trade and tourism.

- The Horn: Djibouti, Eritrea, and Somalia. This is the world's most strategic maritime chokepoint.

Southern Africa: The Bottom of the World

South Africa is the most industrialized nation, but the map of the south is diverse. You have the Kalahari Desert covering much of Botswana. You have the lush deltas of Mozambique.

And then there are the "enclave" countries. Lesotho and Eswatini. Lesotho is particularly cool—it’s a "kingdom in the sky," a country entirely surrounded by South Africa, sitting high up in the mountains. It’s one of the few places in Africa where it regularly snows.

Why the Map Keeps Changing

Think the map is static? Think again.

- South Sudan: The world’s youngest country, born in 2011 after decades of civil war.

- Eritrea: Split from Ethiopia in 1993.

- Western Sahara: If you look at a map in Morocco, Western Sahara doesn't exist; it's just southern Morocco. If you look at a map from the UN, it’s a "non-self-governing territory."

The African Union has a "border program" dedicated to resolving these disputes. They realize that the colonial lines are messy, but they also fear that if they start redrawing them, the whole continent will erupt in conflict. So, for the most part, they stick to the "uti possidetis" principle—basically, "as you possess." Keep the borders you had at independence to avoid chaos.

Navigating the Map: Practical Reality

If you’re planning to travel or do business, don't trust the distances on the map. 500 miles in the US is a day’s drive. 500 miles in parts of the Congo or South Sudan could take a week.

Connectivity is the new map. We are seeing the rise of "corridors." The LAPSSET corridor in East Africa (Lamu Port-South Sudan-Ethiopia-Transport) is an ambitious project to link these nations. The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) is trying to erase the economic borders even if the political ones stay put.

Actionable Insights for the Curious Explorer

- Use the Peter’s Projection or the Gall-Peters Map: If you want to see what Africa actually looks like relative to Europe and North America, look up these maps. They preserve area, even if they distort shapes slightly.

- Check the Visa Map: Before you go, look at the "Africa Visa Openness Index." Some countries, like Rwanda and Seychelles, are incredibly easy to enter. Others are a bureaucratic nightmare. The physical map tells you where the mountains are, but the visa map tells you where the welcome is.

- Download Offline Maps: Google Maps is great in Nairobi or Cape Town. It is useless in the middle of the Namib Desert or the Okavango Delta. Use apps like maps.me that allow for full offline GPS tracking.

- Study the Regional Blocs: To understand how the continent works, don't just look at countries. Look at the EAC (East African Community), ECOWAS (West Africa), and SADC (Southern Africa). These are the real engines of movement and policy.

The map of the countries of africa is a living document. It’s a record of history, a victim of 19th-century cartography, and a blueprint for a massive economic future. Stop looking at it as a static picture and start seeing it as a moving, breathing reality.