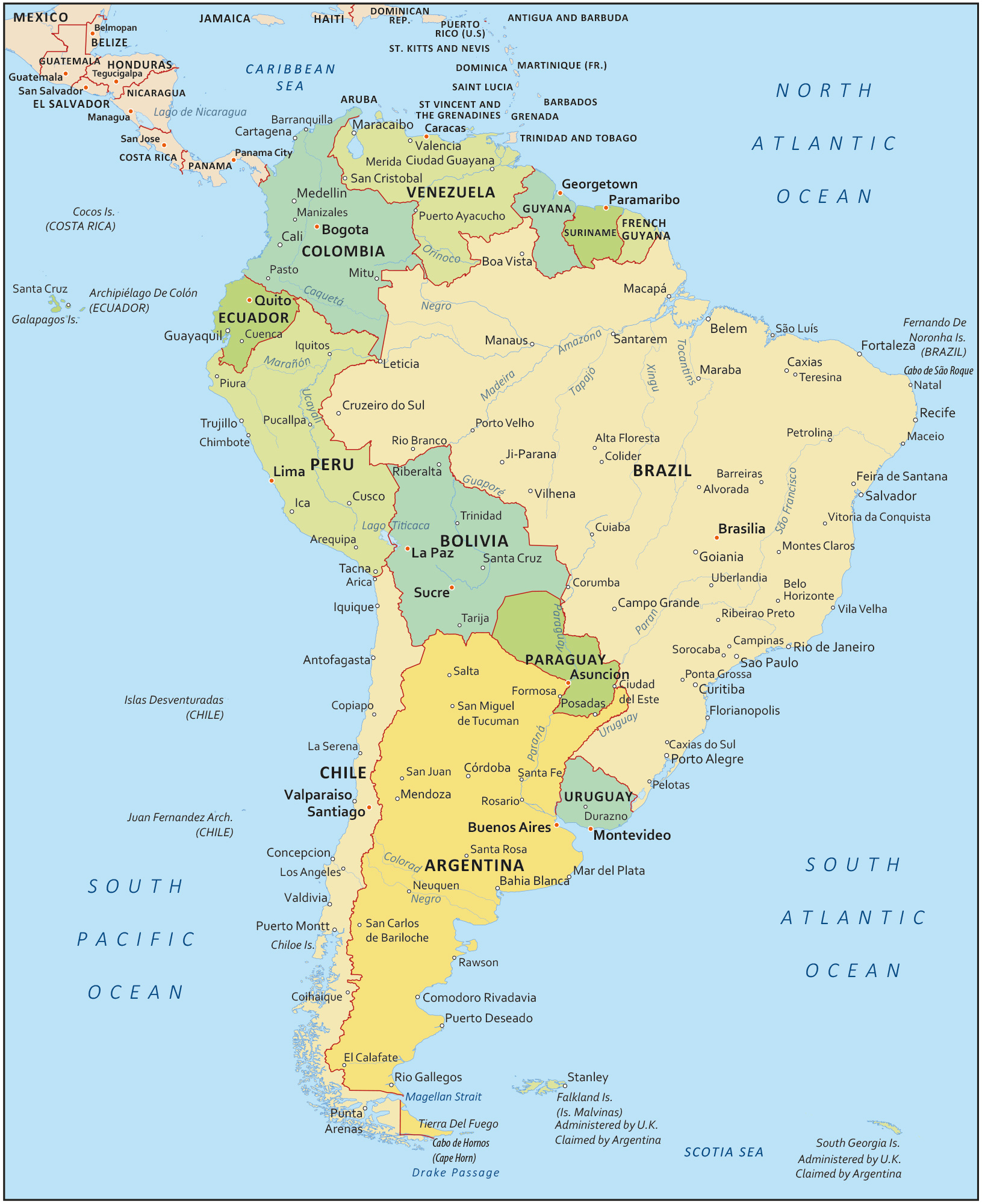

Look at a map of South America. Most people see a giant triangle-ish shape hanging off the bottom of the world. They see the massive green blob of the Amazon. They see the thin, jagged spine of the Andes running down the left side. It looks straightforward. But honestly, if you’re planning a trip or just trying to understand how the continent actually works, that standard map is lying to you—or at least it's leaving out the parts that actually matter.

Maps are basically just lies we all agree on.

Take the borders, for instance. On a flat screen, the line between Chile and Argentina looks like a clean, crisp stroke of a pen. In reality? It’s one of the most rugged, high-altitude, and historically contested boundaries on the planet. I’ve talked to travelers who thought they could just "hop across" from Santiago to Mendoza. They forgot that the "hop" involves crossing a mountain range where Aconcagua sits at nearly 23,000 feet.

The Vertical Map of South America: Altitude is Everything

If you want to understand this place, you have to stop thinking in two dimensions. You need a 3D mindset. In North America or Europe, moving north or south changes the temperature. In South America, moving up 500 feet changes your entire world faster than driving 500 miles south.

Climate zones here are stacked.

Geographers call them pisos térmicos. At the bottom, you have the tierra caliente. It’s hot. It’s humid. It’s exactly what you imagine when you think of the Colombian coast or the Amazon basin. But as you trace your finger across the map of South America and move into the Andes, you hit the tierra templada and eventually the tierra fría. This is where cities like Bogotá or Quito sit. It’s eternal spring. You can stand on the equator and still see snow. That’s the kind of paradox that a standard Mercator projection just can't convey.

📖 Related: Weather San Diego 92111: Why It’s Kinda Different From the Rest of the City

The Altiplano is the weirdest part. It's a massive, high-altitude plateau in the Central Andes, mostly in Bolivia and Peru. It’s the second-largest mountain plateau in the world after Tibet. When you look at it on a map, it just looks like more mountains. When you’re there, it feels like another planet. The air is thin. The light is blindingly bright. The water in Lake Titicaca is a blue so deep it looks fake.

Where the Water Actually Goes

The Amazon River isn't just a line on a map. It’s a cardiovascular system. It drains an area nearly the size of the contiguous United States. People often forget that the Amazon starts in the Andes—just a few dozen miles from the Pacific Ocean—before flowing all the way across the continent to the Atlantic.

Check out the "Meeting of Waters" near Manaus. This is where the Rio Negro, which looks like black coffee, meets the Amazon (Solimões), which looks like milky tea. They run side-by-side for miles without mixing. Why? Different speeds, different temperatures, and different densities. You can see it from space. You can see it on a satellite map of South America, but feeling the temperature change when you dip your hand into the water is a different story.

And then there’s the Pantanal. Most people ignore it because the Amazon gets all the press. But look further south on the map, mostly in Brazil but dipping into Paraguay and Bolivia. It’s the world’s largest tropical wetland. During the wet season, it’s basically an inland sea. During the dry season, it’s the best place on earth to see jaguars.

Borders That Make No Sense (And One That’s a Bridge)

South American borders are weirdly peaceful compared to other parts of the world, but they are geographically insane.

👉 See also: Weather Las Vegas NV Monthly: What Most People Get Wrong About the Desert Heat

- The Triple Frontier: There’s a spot where the Iguaçu and Paraná rivers meet, creating a three-way border between Argentina, Brazil, and Paraguay. You can stand at a viewpoint and see three different countries at once.

- The Atacama Conflict: Look at the map where Chile, Bolivia, and Peru meet. This is the Atacama Desert. It’s the driest non-polar place on Earth. Bolivia used to have a coastline here, but they lost it to Chile in the War of the Pacific back in the 1880s. To this day, Bolivia maintains a Navy—even though they’re landlocked. They use it on Lake Titicaca.

- The French Anomaly: Look at the top right. Most people forget French Guiana is even there. It’s not an independent country; it’s a department of France. They use the Euro. They have the European Space Agency’s primary launch site. Your map of South America technically includes a piece of the European Union.

The Forgotten South: Patagonia and the "End of the World"

Way down at the bottom, the map gets messy. It shatters into thousands of islands, fjords, and channels. This is Tierra del Fuego.

Ushuaia is often called the southernmost city in the world, though Puerto Williams in Chile actually holds the title if you’re being pedantic about population sizes. This region is governed by the "Roaring Forties" and "Furious Fifties"—latitudes where the winds are so strong they can literally blow trucks off the road.

The Strait of Magellan and the Beagle Channel aren't just names from history books. They are treacherous waterways that define the bottom of the map. Before the Panama Canal opened in 1914, every ship going from New York to San Francisco had to navigate these jagged edges. It’s a graveyard of ships.

Biomes You Won’t Find Anywhere Else

We have to talk about the Cerrado. It’s a massive tropical savanna in Brazil. It doesn't get the tourist love the Amazon does, but it’s a biodiversity powerhouse. If you look at a land-use map, you’ll see the Cerrado is being chewed up by soy farms and cattle ranching faster than the rainforest.

Then there’s the Gran Chaco. It’s a hot, dry lowland region divided among Bolivia, Paraguay, Argentina, and Brazil. It’s sparsely populated and incredibly tough to navigate. It’s often called the "Last Frontier." If you’re looking at a map of South America and see a big "empty" space in the middle-south, that’s the Chaco. It’s not empty; it’s just inhospitable to anyone who doesn't know how to live there.

✨ Don't miss: Weather in Lexington Park: What Most People Get Wrong

Infrastructure and the "Road" Problem

One thing the map won't tell you is how hard it is to get around. In Europe, a 300-mile trip is a breezy train ride. In South America, a 300-mile trip on the map might take 15 hours on a bus through mountain switchbacks.

The Pan-American Highway is the "spine" of the map, stretching from Alaska to Tierra del Fuego. But there’s a gap. The Darien Gap. Between Panama and Colombia, the road just... stops. There are about 60 to 100 miles of dense jungle and swampland where no paved roads exist. You can't drive from North America to South America. You have to ship your car or fly over it.

Actionable Insights for Using a Map of South America

If you’re using a map to plan your life or a trip, keep these things in mind:

- Check the Topography: Never look at a "flat" map alone. Always overlay it with a relief map. A distance that looks short might involve crossing three 12,000-foot passes.

- Respect the Seasons: Remember that when it’s summer in the Northern Hemisphere, it’s winter in the south. But "winter" in the Amazon just means it rains more, while "winter" in Patagonia means the roads are closed by snow.

- Flight Hubs vs. Land Travel: The continent is massive. If you’re looking at a map of South America and thinking about "doing it all," you’re going to spend half your time in a bus or a plane. Focus on clusters: the Andean North (Colombia/Ecuador), the Central Andes (Peru/Bolivia), or the Southern Cone (Chile/Argentina/Uruguay).

- The Language Divide: Don't forget that Brazil is roughly half the landmass and population. The map looks unified, but the Portuguese/Spanish divide is the primary cultural boundary.

- Use Digital Tools Wisely: Google Maps is great for cities, but for hiking in the Andes or navigating the backroads of the Pantanal, use offline maps like Maps.me or Gaia GPS. Signal drops out the moment you leave the main hubs.

South America isn't just a place on a page. It's a stacked, layered, and incredibly diverse set of ecosystems that defy simple categorization. The next time you look at that big triangle on the globe, remember that the lines are just the beginning of the story.