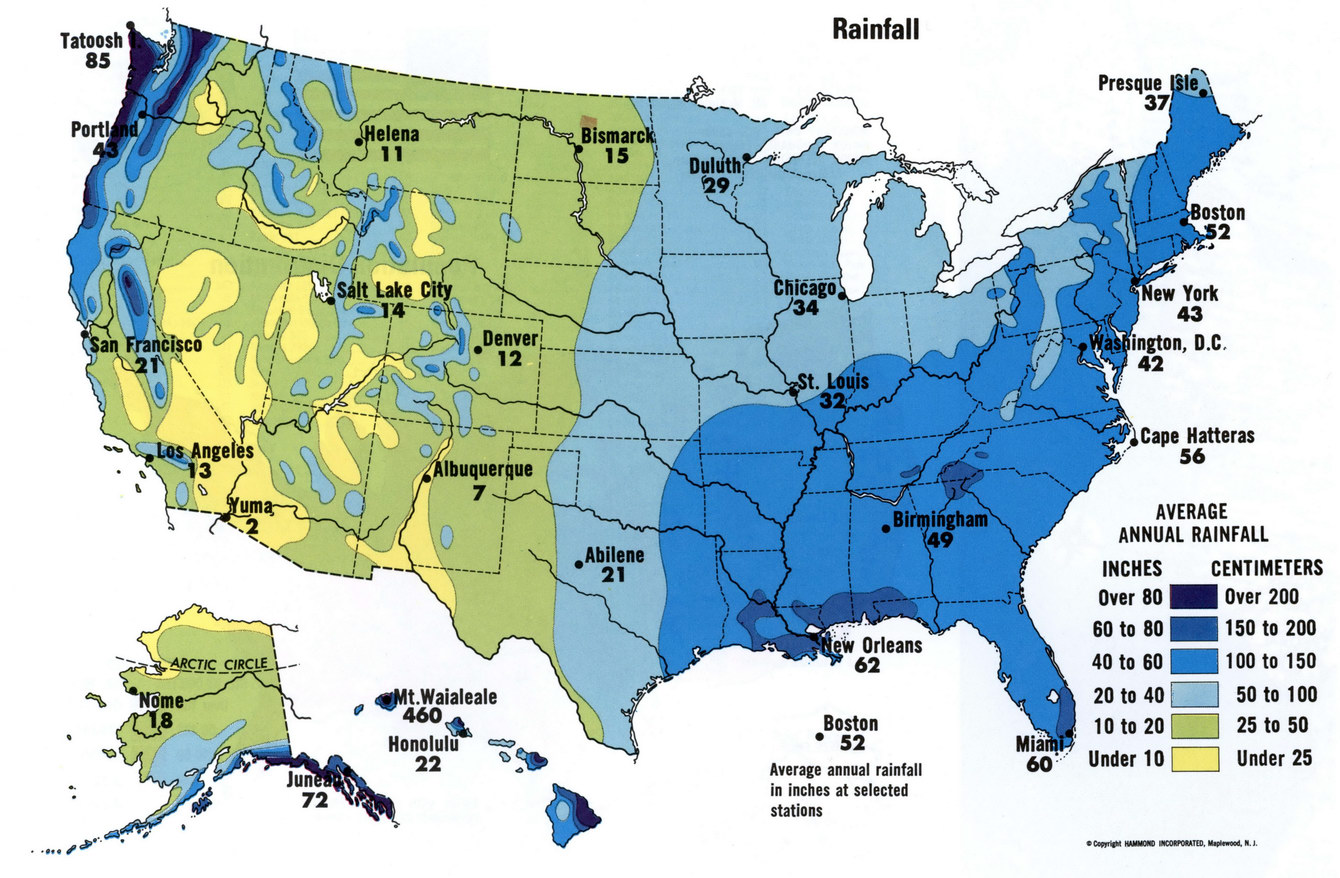

You’ve probably looked at a map of rainfall in the US and thought you knew the deal. The Pacific Northwest is a soggy mess of evergreen trees and drizzle. The Southwest is a scorched pavement of cacti and dust. Florida is basically a giant, humid sponge.

That’s the old story. It’s also kinda wrong now.

Weather patterns in the mid-2020s are acting weird. We aren’t just seeing "more" or "less" rain; we are seeing a total geographic shift in where water lands and how long it stays there. If you’re planning a move, starting a garden, or just wondering why your basement keeps flooding in a "dry" state, the standard precipitation maps from ten years ago are basically fiction.

The Great Shift: Wet Gets Wetter, Dry Gets... Weird

The traditional 100th Meridian—the invisible line slicing through the Dakotas down to Texas—used to be the "Great Divide" of American moisture. East of that line, you had lush farms. West of it, you had the arid frontier.

Climate scientists like Richard Seager from Columbia University have been tracking how this line is physically moving eastward. It’s a slow-motion migration. The "dry" side of the country is effectively expanding its borders. Meanwhile, the Northeast and the Midwest are getting hammered by "rain bombs." This isn't just a catchy term for news anchors. It refers to atmospheric rivers and convective storms that dump a month's worth of rain in six hours.

Take a look at Vermont. Historically, it’s not exactly a tropical rainforest. Yet, recent data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) shows that parts of the Northeast have seen a 70% increase in the amount of precipitation falling in very heavy events since the 1950s.

Contrast that with the Colorado River Basin. Even when they get a "good" snow year, the thirsty soil—parched by years of rising temperatures—soaks up the runoff before it ever hits the reservoirs. The map shows "average" precipitation, but the ground tells a different story.

🔗 Read more: Why Everyone Is Still Obsessing Over Maybelline SuperStay Skin Tint

The Problem With Annual Averages

Most people look at a map of rainfall in the US and see an annual average. This is a massive mistake.

If a city gets 40 inches of rain a year, that sounds great, right? But if 35 of those inches fall in two weeks and the other 50 weeks are a bone-dry drought, the "average" is 40, but the reality is a disaster. Farmers call this "flash drought" followed by "flash flooding."

We’re seeing this play out in the "Corn Belt." Iowa and Illinois used to rely on steady, predictable summer rains. Now, the map shows a jagged pattern of extreme deluge followed by weeks of high-heat evaporation. It’s exhausting for the soil and even worse for the infrastructure.

Why the Gulf Coast is the New Water King

If you want to see where the real action is on a map of rainfall in the US, look at the "Wet Crescent" stretching from East Texas through Louisiana to the Florida Panhandle. This region has always been damp, but the intensification of the hydrological cycle is turning it into a literal deluge zone.

Warm air holds more water.

Basic physics.

💡 You might also like: Coach Bag Animal Print: Why These Wild Patterns Actually Work as Neutrals

For every $1^\circ C$ of warming, the atmosphere can hold about 7% more water vapor. The Gulf of Mexico is currently a hot tub. This means when a storm pulls moisture from the Gulf, it’s not just a rain cloud—it’s a flying ocean. When these systems stall over places like Houston or New Orleans, the rain gauges literally overflow.

The Pacific Northwest, specifically the Olympic Peninsula, still holds the title for the most consistent rainy days, but the Gulf Coast is winning on sheer volume. Mobile, Alabama, often out-rains Seattle by 20 to 30 inches a year. Let that sink in.

The "Shadow" Effect in the West

In the West, rainfall maps are dominated by "Rain Shadows." This is a phenomenon where mountains like the Sierras or the Cascades suck all the moisture out of the air as it rises, leaving the "leeward" side (the inland side) a desert.

- The Windward Side: Think Portland or Seattle. Lush. Mossy.

- The Leeward Side: Think Bend, Oregon or Kennewick, Washington. Sagebrush. Dust.

This contrast is becoming more extreme. As the jet stream gets "wavy," it stays stuck in one position for longer. This creates "blocking patterns." You get three weeks of rain in Seattle while Eastern Washington goes three months without a drop. It’s a feast or famine cycle that’s making the map look like a checkerboard of extremes.

Understanding the "Flash Flood" Alley

We used to worry about Tornado Alley. Now, we should be looking at Flash Flood Alley. This isn't a fixed spot, but it’s increasingly appearing in the Appalachians and the Ohio River Valley.

The topography of the Appalachian Mountains acts as a ramp. Moist air from the south hits the mountains, rises rapidly, cools, and dumps. Because the terrain is rocky and steep, that water doesn't soak in. It runs. This is why small towns in Kentucky and West Virginia—places that aren't on any "hurricane" map—are seeing catastrophic water levels.

📖 Related: Bed and Breakfast Wedding Venues: Why Smaller Might Actually Be Better

The map of rainfall in the US doesn't always show the "slope" factor. A flat acre in Kansas can handle three inches of rain better than a steep holler in Tennessee. When you're looking at these maps, you have to layer them over a topographical map to understand the real risk.

The Mirage of the Southwest Monsoon

For years, people in Arizona and New Mexico lived by the Monsoon. From July to September, the winds would shift, bringing moisture up from the Sea of Cortez. It was like clockwork.

Lately? The clock is broken.

Some years, the monsoon is a "non-soon." Other years, it’s so violent it washes out highways. This unpredictability is the new "normal." Honestly, it makes urban planning in the desert a nightmare. If you can't predict the rain, you can't manage the aquifers. And if you can't manage the aquifers, the cities start to feel a lot more fragile.

Practical Insights for Homeowners and Travelers

Don't just look at a static map of rainfall in the US and assume you’re safe or "dry." Use these strategies to get the real picture:

- Check the "100-Year Flood" Revisions: FEMA is currently rewriting flood maps across the country because the old "100-year" events are happening every five years. If you're buying a home, look at the projected maps, not the historical ones.

- Monitor the Dew Point: Total rainfall is one thing, but humidity is what drives the intensity of the rain. Higher dew points in the Midwest are a leading indicator of coming "rain bombs."

- Invest in Permeable Landscaping: If you live in an area where the map shows increasing rainfall intensity (the Northeast and the South), get rid of the concrete. Rain gardens and permeable pavers allow the water to go into the ground rather than into your living room.

- Watch the Jet Stream: Tools like Windy.com or the National Weather Service long-range forecasts are better than static maps. If the jet stream looks like a roller coaster, expect extreme weather.

- Understand Soil Saturation: A "dry" area on the map can flood if the ground is already saturated from a previous week’s rain. The USDA’s soil moisture maps are a critical secondary resource to any rainfall map.

The geography of American water is being rewritten in real-time. The green parts of the map are moving, the brown parts are deepening, and the blue parts—the places where the water actually falls—are becoming more chaotic. Staying informed means looking past the "average" and paying attention to the spikes.