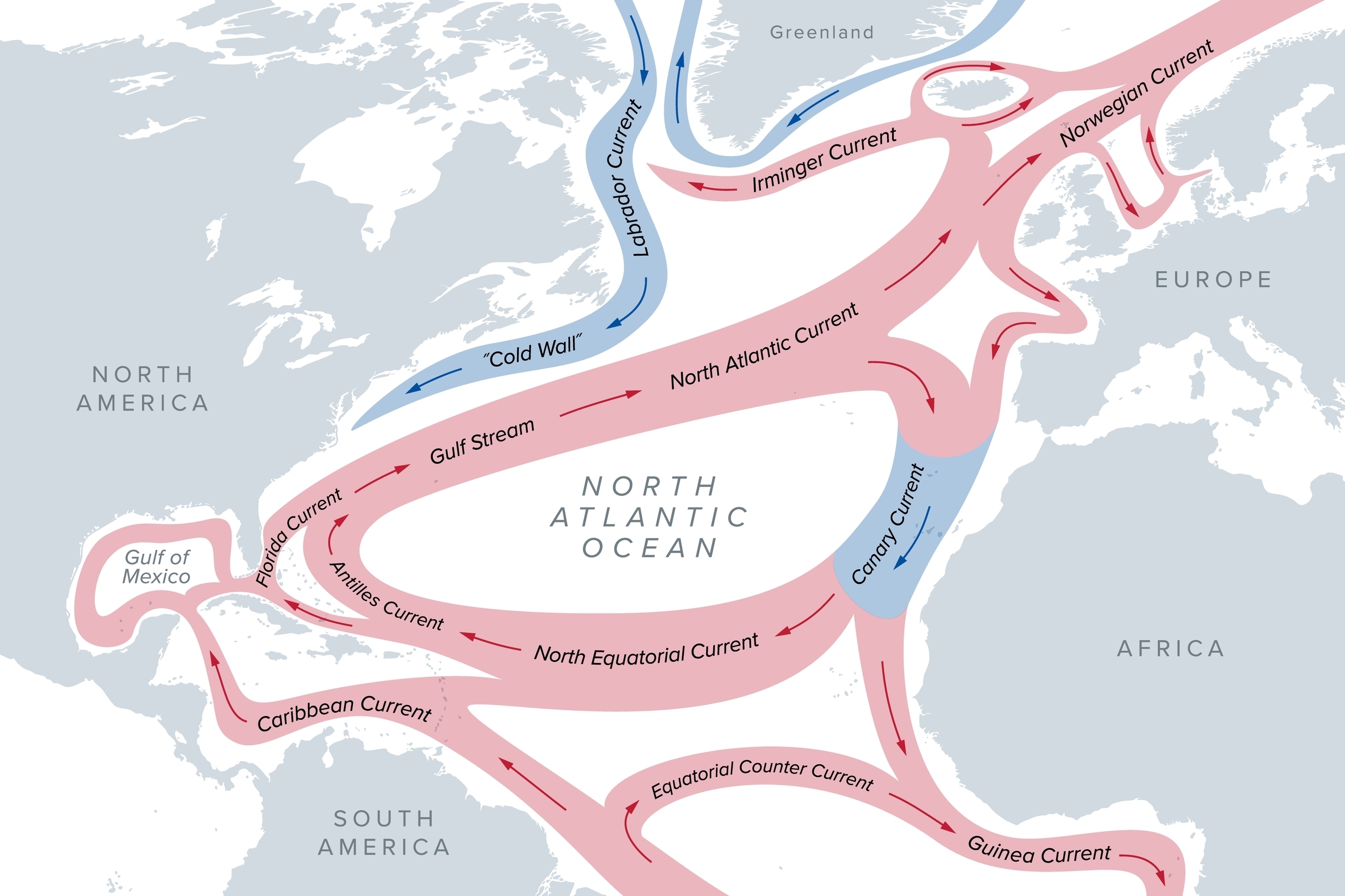

The ocean isn't a bathtub. If you look at a map of ocean currents in the Atlantic, it looks like a neat series of blue and red ribbons, looping gracefully from the equator to the poles. It’s orderly. It’s predictable. Except, honestly, it’s not really like that anymore. These currents are the literal heartbeat of our planet, moving heat around like a giant radiator system, and right now, that radiator is making some very weird noises.

If you’ve ever sat on a beach in North Carolina and felt that strangely warm water, you’ve met the Gulf Stream. It’s the heavyweight champion of the Atlantic. It pushes more water per second than all the world's rivers combined.

The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) Explained

Most people just call it the "Conveyor Belt." Scientists like Dr. Stefan Rahmstorf from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research call it the AMOC. Basically, it’s a massive loop. Warm, salty water travels north from the tropics, hits the cold air near Greenland, sheds its heat (which is why London isn't as frozen as Newfoundland), becomes dense, and sinks.

Once it sinks, it slides back south along the ocean floor. It’s a delicate balance of salt and temperature. If you mess with the salt—say, by melting a massive amount of Greenland's ice—the water doesn't get dense enough to sink.

The engine stalls.

We’re seeing evidence that this engine is at its weakest point in over a thousand years. It’s not just a "theory" for the future; it's happening in the data right now. When the AMOC slows down, the map of ocean currents in the Atlantic changes physically. The "Cold Blob"—a weirdly chilled patch of ocean south of Greenland—is a direct footprint of this slowdown. While the rest of the world is simmering, that one spot is getting colder because the warm water isn't reaching it.

The Gulf Stream isn't just one "River"

Think of the Gulf Stream less like a pipe and more like a messy, fraying rope. It’s full of eddies—swirling vortices of water that break off and spin for months. These eddies are biological hotspots. They trap nutrients and fish, creating moving ecosystems that travel across the sea.

Why the North Atlantic Drift Matters for Europe

Without the North Atlantic Drift (the extension of the Gulf Stream), Europe would be significantly grimmer. We’re talking a drop of 5 to 10 degrees Celsius in some regions. Imagine Paris with the climate of Ottawa. That’s the stakes.

💡 You might also like: Lake House Computer Password: Why Your Vacation Rental Security is Probably Broken

The South Atlantic and the Agulhas Leakage

We often ignore the bottom half of the map. The South Atlantic has the Brazil Current and the Benguela Current. But the real "wild card" is something called the Agulhas Leakage.

Down at the tip of Africa, the Indian Ocean tries to shove warm water into the Atlantic. It comes in these massive "rings"—huge bubbles of warm, salty water that migrate across the South Atlantic. This "leakage" actually helps fuel the AMOC. If the winds in the Southern Ocean shift, the amount of salt entering the Atlantic changes. It’s all connected. You can’t move a pebble in the South Atlantic without ripples showing up in the North.

Deep Water Formation: The Mystery of the Labrador Sea

The Labrador Sea is one of the few places on Earth where the ocean actually "breathes." This is where surface water plunges miles down to the abyss.

Recent studies using the OSNAP (Overturning in the Subpolar North Atlantic Program) array—a massive line of sensors anchored to the sea floor—have shown that the Labrador Sea might not be the main "sink" we thought it was. It turns out the water might be sinking further east, near Iceland and Scotland.

This flipped the script for oceanographers. We’re realizing our maps have been a bit too simplistic for decades. The ocean is more chaotic and localized than the "smooth ribbon" diagrams suggest.

Real-World Impacts on Shipping and Fishing

If you’re a navigator, the map of ocean currents in the Atlantic is a fuel-saving tool. Riding the Gulf Stream north can save a cargo ship thousands of dollars in diesel. But as the current shifts its position—wobbling closer to or further from the US East Coast—those lanes change.

For fishermen, it’s even more stressful. Species like cod and lobster are sensitive to "marine heatwaves" caused by current shifts. In 2012, a massive shift in the Gulf Stream sent water temperatures soaring off the coast of New England, causing the lobster catch to peak way too early and crashing the market price.

📖 Related: How to Access Hotspot on iPhone: What Most People Get Wrong

The Feedback Loops Nobody Talks About

The ocean absorbs about 90% of the excess heat we produce. The currents are the delivery trucks for that heat. When they slow down, the heat stays trapped in the shallows.

- Sea Level Rise: If the Gulf Stream slows, water literally "piles up" against the US East Coast. It’s like a car taking a fast turn; the water sloshes to the outside. When the current slows, that "slope" flattens, pushing water onto the streets of Miami and Norfolk.

- Weather Patterns: A sluggish Atlantic current is linked to more intense heatwaves in Europe and weirder hurricane tracks in the Caribbean.

- Carbon Sequestration: Deep water formation carries CO2 down to the bottom of the ocean. If the water stops sinking, that carbon stays in the atmosphere.

How We Actually Map This (It’s Not Just Satellites)

We use Argo floats. These are cool, yellow robotic tubes that drift through the water. They sink to 2,000 meters, drift for days, and then pop back up to the surface to "phone home" via satellite with their data.

There are about 4,000 of them out there right now.

Before Argo, we had to rely on ships dropping "bottles" or sensors over the side. It was like trying to understand a forest by looking at three trees. Now, we have a grainy, real-time movie of how the Atlantic moves.

Is the "Day After Tomorrow" Scenario Real?

Kinda, but mostly no. The movie where the ocean stops and the world freezes in three days is Hollywood nonsense. Physics doesn't work that fast.

However, a "tipping point" is a real mathematical possibility. Many models suggest that if we hit a certain threshold of freshwater melt from the Arctic, the AMOC could enter a state of collapse that would take centuries to reverse. We wouldn't freeze overnight, but the world's grain belts would shift, and rainfall patterns in the tropics would be devastated.

It's a slow-motion disaster, which is honestly harder for humans to deal with than a giant wave.

👉 See also: Who is my ISP? How to find out and why you actually need to know

Looking Forward: Tracking the Changes

Understanding the map of ocean currents in the Atlantic isn't just for sailors anymore. It’s for city planners in New York, farmers in France, and insurance companies in Florida.

We are currently in a race to build better "digital twins" of the ocean. Using AI and the massive data stream from Argo floats, researchers are trying to predict current shifts months in advance.

What you should do next:

If you want to see this in motion, check out the Nullschool Earth Map or the NASA Scientific Visualization Studio. They provide real-time overlays of current speeds and temperatures. You can actually see the eddies spinning off the Gulf Stream today.

Keep an eye on the "Sea Surface Temperature Anomaly" maps for the North Atlantic. If you see that cold blue patch near Greenland getting bigger while the rest of the Atlantic is deep red, you're looking at the AMOC slowing down in real-time. Understanding these patterns is the first step in preparing for a coast that's going to look very different in twenty years.

Educate yourself on local coastal resilience plans. If you live on the East Coast, the speed of the Atlantic currents determines how often your basement floods. It’s not just "the ocean"—it’s a dynamic, moving system that dictates the terms of life on land.