Most people look at a map of North American deserts and see a whole lot of nothing. They see brown splotches on a page. Maybe they think of Wile E. Coyote or a dusty Vegas vacation. Honestly, that's a mistake. These landscapes cover over a million square miles. It's a massive, interconnected system of grit, heat, and surprisingly, a lot of freezing cold.

You've probably heard of Death Valley. Everyone has. But if you look at the actual geography, the story isn't just about heat records in California. It's about a rain shadow effect created by the Sierra Nevada and the Cascade mountains. These giants literally strip the moisture out of the air. By the time that wind hits the interior, it’s bone dry. That's how you get a desert.

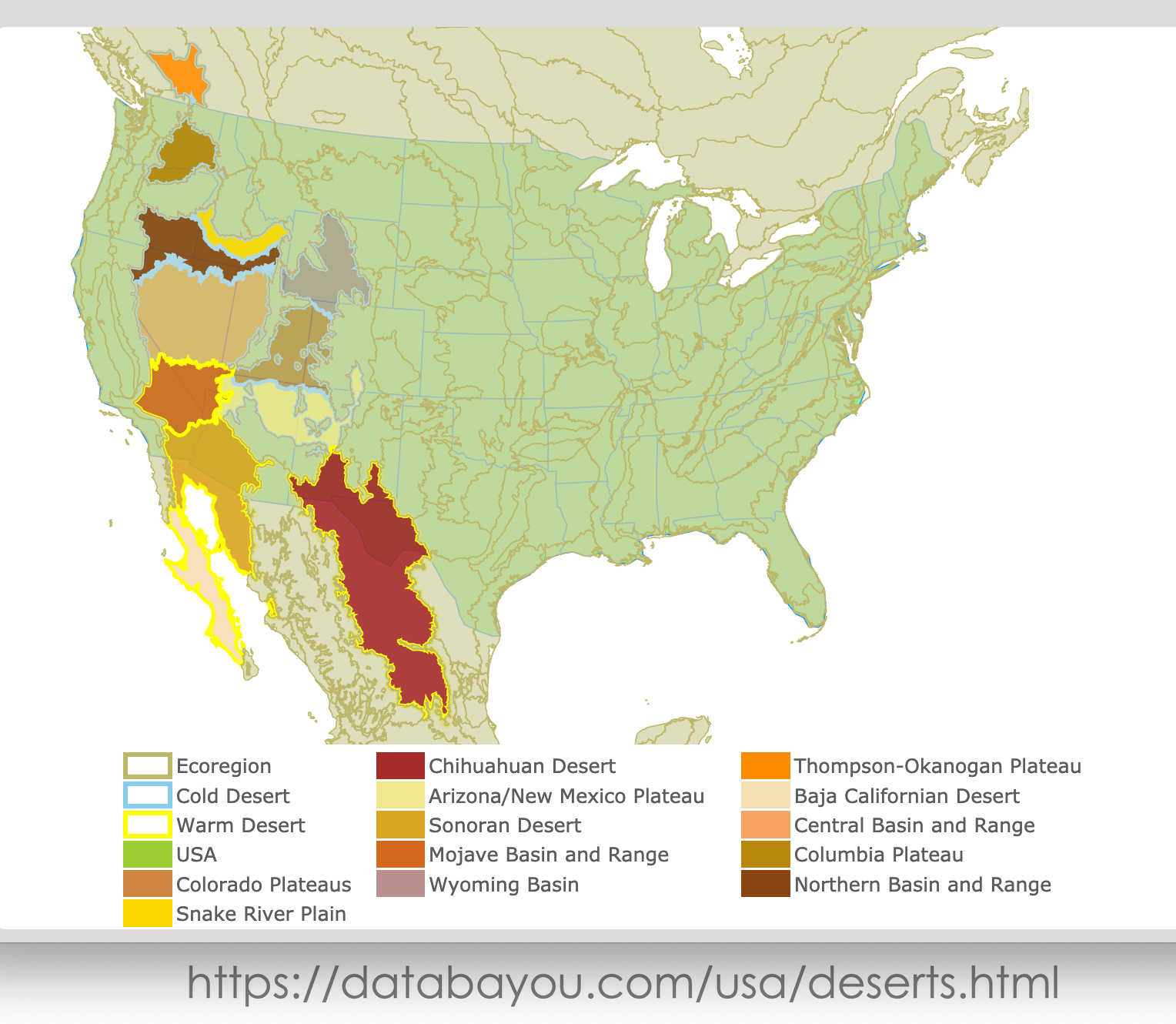

The North American desert system is generally split into four distinct regions. Most scientists—folks like those at the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS)—break it down by "cold" and "hot" deserts. The Great Basin is the big cold one. Then you have the three hot ones: the Mojave, the Sonoran, and the Chihuahuan.

They all touch. They all overlap. It's a giant, shifting puzzle of sand, rock, and sagebrush.

The Great Basin: A High-Altitude Icebox

If you start at the top of a map of North American deserts, you hit the Great Basin. It's huge. It covers most of Nevada, half of Utah, and spills into Oregon and California. This isn't your "classic" desert with giant saguaro cacti. You won't find those here. It's too cold.

Instead, you get sagebrush. Miles and miles of it.

The Great Basin is a "cold desert" because most of its precipitation falls as snow. It’s high up. We're talking 4,000 to 6,000 feet above sea level for the valley floors. In the winter, it’s brutal. You could be standing in the middle of a desert and literally freezing your nose off. It’s also "endorheic." That's a fancy word meaning the water doesn't flow to the ocean. It just pools into salty sinks like the Great Salt Lake or evaporates into nothing.

People forget how lonely this part of the map is. Drive Highway 50 across Nevada—the "Loneliest Road in America"—and you'll see exactly what I mean. It's just basin, range, basin, range. Over and over. It feels like the earth is a giant crumpled piece of paper.

The Mojave: The Smallest but Deadliest

Down south, the Great Basin starts to blend into the Mojave. This is the transition zone. If you’re looking at a map, look for the Joshua Tree. That’s the Mojave’s calling card. If you see a Joshua Tree, you’re in the Mojave. If you don't, you've probably crossed a line into another climate zone.

💡 You might also like: Weather in Lexington Park: What Most People Get Wrong

The Mojave is the smallest of the four. Don't let that fool you. It holds the record for the hottest temperature ever recorded on Earth at Furnace Creek in Death Valley. 134 degrees Fahrenheit. Think about that. That’s not just "hot." That’s "your shoes might melt" hot.

The Mojave is also home to the Kelso Dunes. These are massive piles of sand that actually "sing" or boom when the wind hits them just right. It’s a low-frequency hum that vibrates in your chest. Geologists call it "singing sand," and it happens because the grains are shaped just right to create friction.

The Sonoran: The Green Desert

Now, if you keep moving south on that map of North American deserts, you hit the Sonoran. This covers southern Arizona and a huge chunk of Mexico. This is the desert from the movies.

This is where the Saguaro lives.

The Sonoran is weird because it actually gets two rainy seasons. You get the winter rains from the Pacific and then the summer monsoons from the Gulf of California. Because of all that water, it's incredibly lush. Well, lush for a desert. You've got palo verde trees, prickly pears, and creosote bushes everywhere.

It’s also the only place in the world where the Saguaro cactus grows wild. These things are giants. They can live for 200 years and grow to 50 feet tall. But they’re slow. A Saguaro might take ten years just to grow an inch. When you see one with "arms," it's usually at least 75 to 100 years old.

One thing people get wrong about the Sonoran is the elevation. It’s much lower than the Great Basin. That’s why it stays so much warmer in the winter. Phoenix and Tucson are the hubs here, and they’ve basically turned the desert into a massive urban sprawl. This creates a "heat island" effect. The asphalt holds the heat all night, so the desert never actually gets a chance to cool down like it used to.

The Chihuahuan: The High Plateau

Finally, you’ve got the Chihuahuan Desert. This is the big boy. It’s the largest desert in North America, but most of it is in Mexico. On the U.S. side, it takes up West Texas and parts of New Mexico.

📖 Related: Weather in Kirkwood Missouri Explained (Simply)

Unlike the Mojave or the Sonoran, the Chihuahuan is a high-altitude desert. Most of it sits above 3,500 feet. This means it has very cold winters and very hot summers. It’s famous for its "sky islands." These are basically mountains that stick up out of the desert floor like islands in an ocean. At the bottom, it's cactus and dirt. At the top, it’s pine trees and bears.

Big Bend National Park is the crown jewel here. The Rio Grande cuts right through these massive limestone canyons. It’s rugged. It’s also home to the White Sands in New Mexico. That’s actually a gypsum desert. Most sand is made of silica, but this is basically just soft, white plaster. It’s cool to the touch even in the midday sun because it reflects the light instead of absorbing it.

Why the Map is Changing

Maps aren't permanent. Climate change is physically moving the borders of these deserts. Aridification—that's the process of land becoming drier—is pushing desert conditions further north into places like Idaho and Montana.

The "Dust Bowl" wasn't just a 1930s fluke. It was a warning.

We’re seeing the "Mojave-ization" of the Great Basin. As temperatures rise, the hardy sagebrush is being pushed out by invasive grasses like cheatgrass. This stuff burns like gasoline. When the Great Basin burns, the native plants don't come back. The desert just gets drier and more prone to fire.

Water is the real story on any map of North American deserts. The Colorado River is the lifeblood for millions of people living in these dry zones. But the river is struggling. Lake Mead and Lake Powell—the two biggest reservoirs in the U.S.—have hit historic lows in recent years. We are basically "mining" water that was deposited thousands of years ago during the last ice age. Once it’s gone, it’s gone.

Biodiversity and the "Empty" Myth

There is a huge misconception that deserts are dead zones. That is completely false. The Sonoran Desert alone has over 2,000 species of plants.

- Cryptobiotic soil: If you’re hiking in the High Desert, you might see "black crust" on the dirt. Don't step on it. That’s a living community of cyanobacteria, lichens, and mosses. It holds the desert together. One footprint can take 50 years to heal.

- Gila Monsters: One of the only venomous lizards in the world lives in the Sonoran. They spend 90% of their lives underground.

- The Ocelot: Yes, there are wild cats that look like mini-leopards living in the thorny brush of the Chihuahuan and Sonoran fringes.

The desert is actually teeming with life; it just has better hiding skills than animals in the forest. Most desert creatures are nocturnal. They wait for the sun to drop before they even think about moving.

👉 See also: Weather in Fairbanks Alaska: What Most People Get Wrong

Survival and Exploration Realities

If you’re planning to use a map of North American deserts to actually go out and explore, you need a reality check. Modern GPS is great until your phone overheats and shuts off. And it will shut off in 110-degree heat.

The desert doesn't kill you with just heat. It kills you with "insensible perspiration." This is when your sweat evaporates so fast you don't even feel wet. You’re dehydrating and you don't even realize you’re sweating. You need at least a gallon of water per person per day. If you’re hiking, make it two.

Also, watch the washes. A "wash" is a dry creek bed. On a map, they look like little blue dashed lines. In person, they look like a flat, sandy road. If it rains ten miles away, that wash can turn into a wall of water and debris in minutes. Flash floods are the number one weather-related killer in the desert.

Actionable Insights for Your Next Trip

If you want to experience these places without ending up as a cautionary tale on a park ranger’s blog, do this:

- Visit in the "Shoulder" Seasons: Go to the Mojave in October or the Sonoran in March. You'll get the wildflowers without the heatstroke.

- Learn the "Sky Island" Trick: If it's 100 degrees in Tucson, drive up Mount Lemmon. For every 1,000 feet you climb, the temperature drops about 3 to 5 degrees. You can go from cactus to pine trees in 45 minutes.

- Check the "Biotic Crust": When hiking in Utah or Nevada, stay on the trails. That weird, crunchy black dirt is what keeps the desert from turning into a giant dust bowl.

- Tire Pressure Matters: If you’re driving off-road in the Chihuahuan or Mojave, lower your tire pressure slightly for better traction in sand—but make sure you have a compressor to pump them back up before hitting the highway.

- Night Sky Orientation: The Great Basin has some of the darkest skies left in the lower 48 states. Places like Great Basin National Park are "International Dark Sky Parks." Bring a telescope, not just a map.

The deserts of North America aren't just empty spaces on a map between the "important" cities. They are complex, vibrating ecosystems that are currently under immense pressure from drought and development. Understanding the map is the first step toward respecting how fragile these landscapes really are.

Source References:

- U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) - Desert Regions of North America

- National Park Service - Death Valley and Saguaro National Park Guides

- The Nature Conservancy - Chihuahuan Desert Ecoregion Report

- Bureau of Land Management (BLM) - Great Basin Ecosystem Management

The North American desert is a place of extremes. It's where the earth is stripped bare, showing you exactly what it's made of. Whether it's the towering saguaros of Arizona or the frozen sagebrush plains of Nevada, these landscapes demand a level of respect that few other places on Earth do. Pack more water than you think you need, stay on the trail, and keep your eyes on the horizon. The desert is always bigger than it looks on paper.