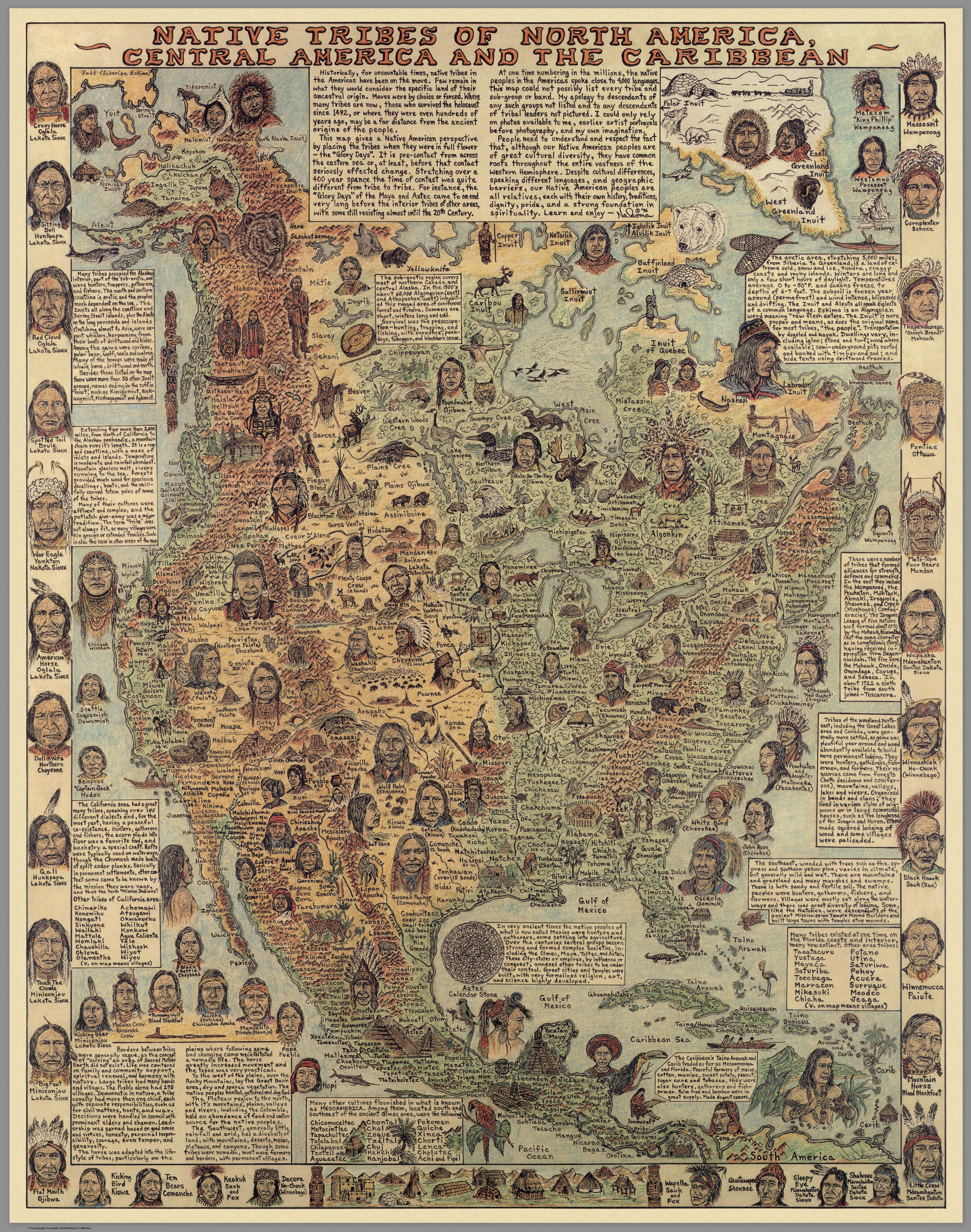

You’ve seen them in history books or dusty classroom corners. Those colorful posters showing neat, colored borders where the Sioux lived here and the Iroquois lived there. It looks clean. Organized. Almost like a map of modern Europe or the 50 states.

Except it’s mostly a lie.

Not a malicious lie, usually. But the map of native tribes of North America that we grew up with is a massive oversimplification of a continent that was—and is—messier, more vibrant, and way more politically complex than a single piece of paper can capture. Honestly, trying to pin down these boundaries is like trying to map the wind. It changed with the seasons, the buffalo migrations, and the rise and fall of massive trading empires that lasted centuries before a single European ship hit the coast.

The Problem with Static Borders

Most maps you find online are "pre-contact" snapshots. But what does that even mean? "Contact" happened in 1492 in the Caribbean, but it didn't hit the Pacific Northwest for another 250 years. A map of native tribes of North America from 1500 looks nothing like one from 1700.

Take the Lakota.

Most people think of them as the ultimate Great Plains horse culture. But in the 1600s, they were largely woodland people in what we now call Minnesota. They moved west because of pressure from the Anishinaabe (who had acquired French firearms) and the lure of the horse. So, if your map shows the Lakota in South Dakota in the year 1550, that map is factually broken.

Static maps fail because Indigenous life was about relationships and movement, not property lines. Think of it more like a Venn diagram. You had "shatter zones" where multiple groups hunted, traded, and occasionally fought. The Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy didn't just sit in upstate New York; their influence and "tributary" zones stretched down to the Carolinas and west to the Mississippi.

👉 See also: How is gum made? The sticky truth about what you are actually chewing

It's About Language, Not Just "Tribes"

The word "tribe" is kinda loaded. It suggests a small, isolated group. But many of these were nations or massive linguistic families. When you look at a map of native tribes of North America, you’re often looking at two different things at once: linguistic groups (like Algonquian or Athabaskan) and specific political entities (like the Cheyenne or the Miami).

It’s easy to get confused.

The Athabaskan language family is a great example of why maps get weird. You find Athabaskan speakers in the freezing interior of Alaska and Northern Canada, but you also find them in the scorching deserts of the Southwest—the Navajo (Diné) and Apache are linguistically related to those northern groups. They migrated. Maps usually struggle to show that deep-time movement, opting instead for a "static" moment that never really existed in isolation.

The Real Power Players

If you really want to understand the geography, you have to look at the "Three Fires" or the "Seven Council Fires." These weren't just random clusters of people. They were sophisticated geopolitical alliances.

- The Haudenosaunee: Often called the Iroquois, they had a constitution (The Great Law of Peace) that some historians, like Donald Grinde Jr., argue influenced the U.S. Constitution. Their map isn't just a patch of land; it’s a web of diplomatic influence.

- The Mississippian Culture: Go back to 1100 AD, and the map looks like a series of massive city-states. Cahokia, near modern-day St. Louis, was bigger than London at the time. It had massive earthen mounds and a trade network that brought shark teeth from the Gulf and copper from the Great Lakes to a single urban hub.

- The Comanche Empire: By the 18th century, the Comanche (Numunuu) controlled a massive swath of the Southern Plains known as the Comancheria. As Pekka Hämäläinen points out in his definitive work on the subject, they weren't just "living" there; they were an imperial power that dictated terms to the Spanish and Mexicans.

Why "Empty Space" Is a Myth

One of the biggest issues with a standard map of native tribes of North America is the white space. We tend to think if a name isn't written there, nobody lived there.

Wrong.

✨ Don't miss: Curtain Bangs on Fine Hair: Why Yours Probably Look Flat and How to Fix It

Pretty much every square inch of the continent was managed. In California, what looked like "wild" land to Spanish explorers was actually a highly manicured garden. Tribes used controlled burns to manage oak groves for acorns. In the Pacific Northwest, the Tlingit and Haida managed "sea gardens" and salmon runs with the precision of a modern agricultural firm.

When you look at a map, you should be seeing a 100% filled-in puzzle. There was no "wilderness." There was only home.

The Digital Revolution in Mapping

If you’re tired of the old, inaccurate maps, you’ve got to check out Native-Land.ca. It’s a project run by Native Land Digital, and it’s basically the gold standard for how we should view the map of native tribes of North America today.

It doesn't use hard lines.

Instead, it uses overlapping colors. If you click on a spot in, say, Chicago, it shows you that this land belongs to the Council of the Three Fires (Ojibwe, Potawatomi, and Odawa) as well as the Menominee, Miami, and Ho-Chunk. It acknowledges that land can belong to—and be cared for by—more than one group at a time. This "blurriness" is actually more scientifically and historically accurate than a sharp line.

Mapping the Modern Reality

We can't talk about the map without talking about the reservations. But even that is a simplification.

🔗 Read more: Bates Nut Farm Woods Valley Road Valley Center CA: Why Everyone Still Goes After 100 Years

Today, there are 574 federally recognized tribes in the U.S. alone, and hundreds more in Canada (First Nations, Métis, and Inuit). Some have huge land bases, like the Navajo Nation, which is larger than West Virginia. Others have "checkerboard" land where tribal property is interspersed with non-native land, making a physical map look like a chaotic quilt.

And then there's the "Urban Indian" reality. Over 70% of Indigenous people in the U.S. live in cities. So, while the map of native tribes of North America usually focuses on ancestral homelands or reservations, the "human map" of where the people actually are is centered in places like Los Angeles, Phoenix, and New York City.

How to Actually Use This Information

If you're a teacher, a researcher, or just someone who wants to get it right, stop looking for the "one true map." It doesn't exist. Instead, follow these steps to get a more nuanced view of the geography:

- Check the Date: Always ask, "What year does this map represent?" If it doesn't say, it's probably a collage of different eras and should be viewed with skepticism.

- Look for Overlap: If a map shows clean, non-touching borders, it's ignoring the reality of trade, shared hunting grounds, and diplomacy.

- Identify the Source: Is the map made by the people it depicts? Indigenous-led mapping projects prioritize different landmarks—often water sources, sacred sites, or traditional trails—rather than the colonial borders of states and provinces.

- Acknowledge Displacement: Many tribes on the map of native tribes of North America are no longer where they started. The Trail of Tears is the most famous example, moving the Cherokee, Muscogee (Creek), Seminole, Chickasaw, and Choctaw from the Southeast to Oklahoma. A real map should show the connection between the ancestral home and the current sovereign land.

The geography of North America is a story of layers. You have the ancient geological layer, the Indigenous layer that spans over 15,000 years (at least), and the relatively thin veneer of colonial borders that have only been here for a few centuries.

When you look at a map of native tribes of North America, you aren't just looking at history. You're looking at a living, breathing political reality. These aren't "extinct" groups. They are sovereign nations with their own laws, license plates, and governments. The map is still being written.

Next Steps for Deepening Your Knowledge

- Locate your current position: Visit Native-Land.ca and enter your zip code or city. Identify the specific nations whose ancestral lands you currently occupy.

- Research "Land Acknowledgements": Look beyond the scripted versions and find the specific history of the treaties (or lack thereof) in your specific region.

- Support Indigenous Cartography: Follow projects like the Indigenous Mapping Collective to see how modern technology like GIS is being used to reclaim traditional place names and manage natural resources.

- Read the Nuance: Pick up a copy of An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz to understand the movements and political shifts that these maps try—and often fail—to illustrate.