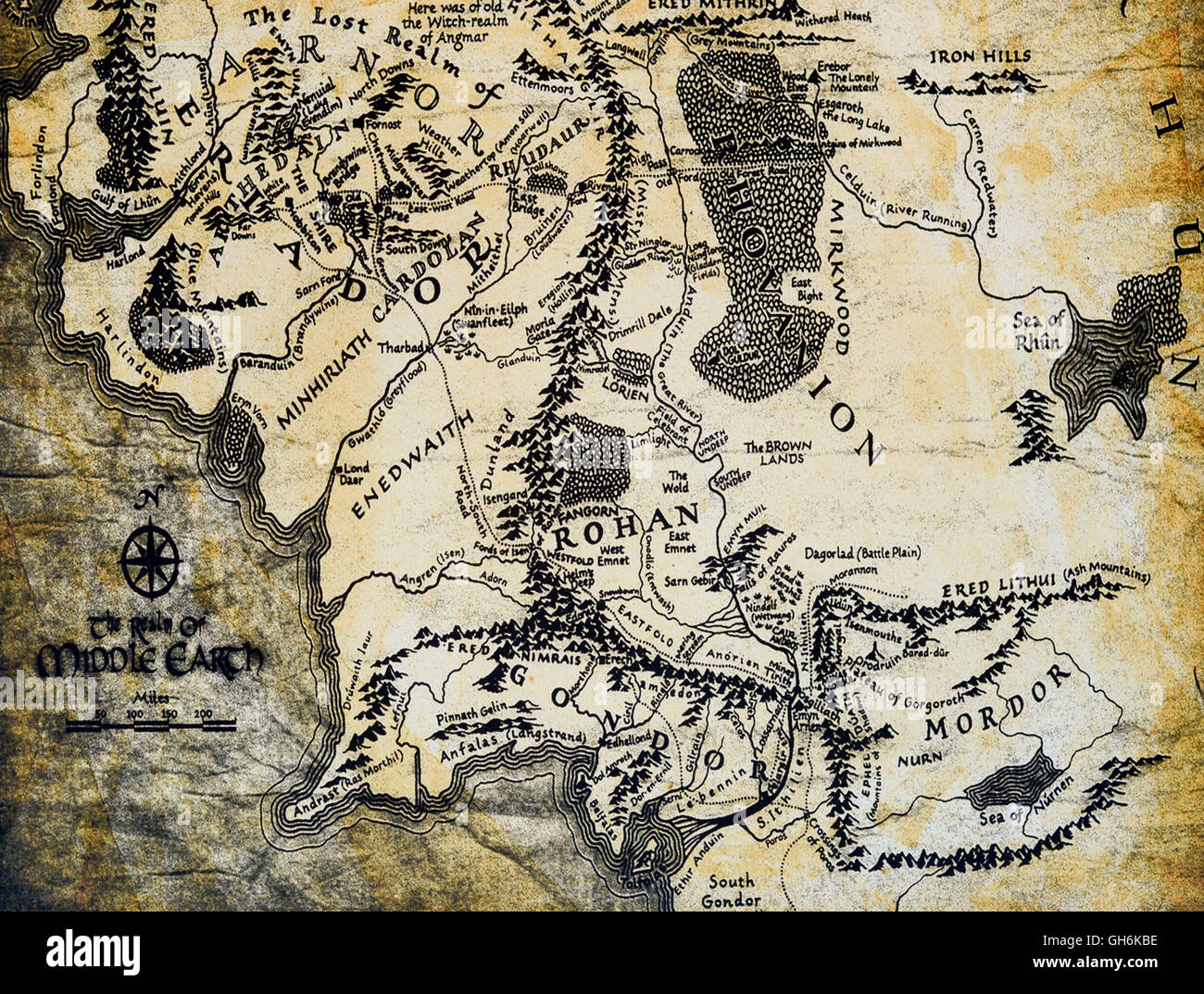

If you open a copy of The Fellowship of the Ring, you’ll find it almost immediately. It’s usually tucked right there in the front or back of the book, a sprawling, hand-drawn landscape of jagged mountains, dense forests, and winding rivers. The map of Middle-earth by Tolkien isn't just a guide for readers who get lost between Bree and Rivendell. It’s the skeleton of the entire Legendarium.

Maps are usually an afterthought. For J.R.R. Tolkien, the map was the foundation. He famously said he wisely started with a map and made the story fit. If you don't do that, you get stuck in inconsistencies that ruin the "secondary belief" of the reader. He was obsessed with the distance a Hobbit could walk in a day. He tracked the phases of the moon. He knew exactly how many miles lay between the Rauros falls and the Black Gate.

The messy reality of the original sketches

People think the map we see today was some pristine vision that popped out of Tolkien's head fully formed. It wasn't. The "First Map," which is currently held in the Marquette University archives, is a chaotic mess of pencil marks, ink, and even some red chalk. It was a working document. Tolkien would literally stick extra pieces of paper onto the edges with tape when he realized his characters had walked off the edge of his original world.

Christopher Tolkien, the Professor’s son, is the person we actually have to thank for the version we recognize. In 1953, he was tasked with redrawing his father’s sprawling, messy sketches into something a printer could actually handle. He spent hours laboring over the calligraphy and the coastline. He even admitted later that he made a few mistakes, particularly with the placement of some mountain ranges in the south.

Think about the scale. It's massive. But it’s also remarkably empty in places. Tolkien didn't feel the need to fill every square inch with "Point of Interest" markers like a modern open-world video game. He left blanks. The "Withered Heath" or the "Far Harad" stay mysterious because the characters never go there. That’s the magic of it.

Why the map of Middle-earth by Tolkien feels like a real place

The geography makes sense. It’s not just random mountains thrown at a page. Tolkien was a philologist, but he had a keen eye for how the natural world worked. Look at the Anduin, the Great River. It flows from the north, fed by the Misty Mountains, and snakes its way down to the sea. It dictates the politics of the world. Gondor is powerful because it controls the river's delta and the crossing at Osgiliath.

👉 See also: Is Heroes and Villains Legit? What You Need to Know Before Buying

Geology matters here. The Misty Mountains aren't just a wall; they are a barrier that defines the isolation of Eriador from the Vales of Anduin. When the Fellowship tries to cross at Caradhras, they aren't just fighting "plot." They are fighting the specific, cold reality of a high-altitude pass.

Most fantasy maps today look like they were generated by an algorithm. They have "The Desert" in one corner and "The Ice Land" in another. Tolkien’s map feels lived-in. You can see where old kingdoms like Arnor used to be just by looking at the ruins marked on the map, like Amon Sûl (Weathertop). It’s a map of a world that has already ended several times over.

The influence of the "First Age" maps

You can’t really understand the Third Age map without looking at Beleriand. This was the land to the west that sank beneath the sea at the end of the First Age. If you look at the map of Middle-earth by Tolkien from the Lord of the Rings era, the Blue Mountains (Ered Luin) on the far left are actually the remnants of a much larger mountain range from the ancient days.

This gives the world a sense of "depth." When Elrond or Galadriel look at the map, they aren't just seeing geography. They are seeing ghosts. They remember when the land extended hundreds of miles further west.

The controversy of the "Squared-off" mountains

If you show a professional geologist the map of Middle-earth, they might point out something weird. Look at Mordor. It’s basically a perfect square of mountains. The Ered Lithui and the Ephel Dúath meet at right angles. In nature, that almost never happens. Tectonic plates don't usually move in perfect squares.

✨ Don't miss: Jack Blocker American Idol Journey: What Most People Get Wrong

Some fans argue this is proof that Sauron used magic to raise those mountains as a fortress. Others think it was just Tolkien’s way of creating a visual "prison" for the antagonist. Honestly, it doesn't matter if it's "unrealistic." It’s iconic. It tells you everything you need to know about the character of the land before you even read a word of the text. Mordor is unnatural. It is a scar on the world.

Variations and the "Pauline Baynes" version

In 1970, a poster map was released that many fans consider the definitive "color" version. It was illustrated by Pauline Baynes. Tolkien actually worked with her on it, providing tiny, meticulous notes. He gave her specific instructions on the flora—what kind of trees grew in which regions. He even suggested that Minas Tirith should be at a similar latitude to Florence, Italy, while the Shire was more akin to the English Midlands.

This is a key bit of trivia: Middle-earth isn't another planet. Tolkien was very clear that this is our Earth, just in a purely fictional period of pre-history.

- The Shire: Roughly 52 degrees North (Oxford/Birmingham).

- Minas Tirith: Roughly 43 degrees North (Tuscany/Florence).

- The Sea of Rhûn: Representing the vast inland seas of the East.

How the map changed the fantasy genre forever

Before Tolkien, maps in books were rare or decorative. After him, they became a requirement. George R.R. Martin, Robert Jordan, Brandon Sanderson—they all owe the visual identity of their worlds to the map of Middle-earth by Tolkien.

But there’s a trap here. A lot of modern authors draw a map first and then try to make the story follow it like a GPS. Tolkien’s process was more organic. He drew the map, wrote the story, realized the map was wrong, fixed the map, and then re-wrote the story. It was a constant dialogue between the visual and the verbal.

🔗 Read more: Why American Beauty by the Grateful Dead is Still the Gold Standard of Americana

The map also serves as a scale of hope. When you see how far Frodo and Sam have to go—from the top left corner all the way to the bottom right—it makes their journey feel impossible. You can visually measure the distance from the safety of the Shire to the literal mouth of hell. Without that visual aid, the sheer exhaustion of the characters wouldn't land the same way.

Common misconceptions about Middle-earth's geography

A lot of people think Middle-earth is the name of the whole world. It's not. The world is called Arda. Middle-earth (or Ennor) is just one continent. To the west is Aman, the Undying Lands, which was removed from the physical "circles of the world" after the fall of Númenor. This is why the world became round—before that, it was basically flat.

Another big one: the "Mountains of Power" or "Iron Mountains" aren't on the standard map. Those were far to the north, where Melkor (the original Dark Lord) had his fortress of Utumno. By the time of The Lord of the Rings, those are mostly gone or buried under ice.

Actionable ways to explore the map today

If you really want to get into the weeds of Middle-earth geography, you shouldn't just look at the one in the back of your book.

- Study "The Atlas of Middle-earth" by Karen Wynn Fonstad. This is widely considered the gold standard. She was a professional cartographer who took Tolkien’s notes and applied real-world geological and meteorological principles to them. She maps out the troop movements, the paths of the characters, and even the floor plans of places like Orthanc.

- Check the interactive maps online. There are several fan-made projects that allow you to zoom in on specific regions like Ithilien or the Pelennor Fields. These often include timelines, so you can see where every character was on a specific date.

- Look at the "First Map" reproductions. Seeing Tolkien’s own messy handwriting and his taped-on additions gives you a much deeper appreciation for the creative process. It makes the world feel less like a finished product and more like a living, breathing project.

- Compare the different "Ages." Find a map of Beleriand (The First Age) and overlay it with the Third Age map. Seeing how the coastlines changed helps you understand the cataclysmic events that shaped the history of the Elves.

The map of Middle-earth by Tolkien is a document of a man's obsession with consistency and beauty. It’s a testament to the idea that a story is only as good as the ground it stands on. Next time you open the book, don't just skip past the map. Look at the scale bar. Look at the way the mountains of Angmar curve. Everything is there for a reason.

To truly master the layout of this world, start by tracing the journey of the Ring. Note the river crossings and the mountain passes. Observe how the terrain dictates the speed of the narrative. Geography, in Tolkien's world, is destiny.