When you look at a modern satellite image of Tokyo, it's basically a gray-and-green sprawl. But if you peel back the layers and look at a map of Japan Edo period style, something clicks. You start to see the bones of the city. You see why the trains run where they do, and why some neighborhoods feel like cramped mazes while others have these massive, wide-open boulevards.

It wasn't just about geography.

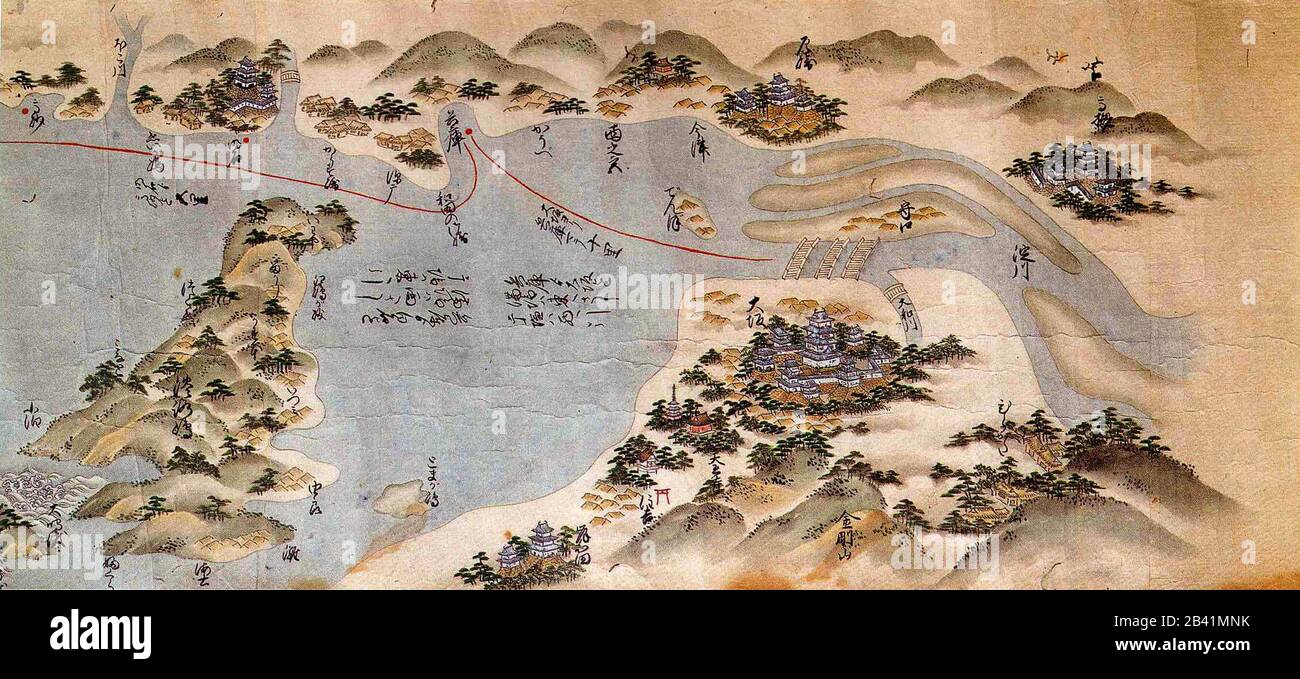

These maps were political statements. They were tools of control. Honestly, the way the Tokugawa shogunate used cartography is kind of genius, if a little terrifying. They didn't just map the land; they mapped the social hierarchy.

The Chaos and Order of the Edo Period Map

Back in the early 1600s, Japan was coming off a century of brutal civil war. Peace was new. It was fragile. Tokugawa Ieyasu, the big boss who finally unified the country, knew that if he wanted to keep power, he needed to know exactly who owned what and where every single rice paddy was located.

The early map of Japan Edo projects were massive undertakings called Kuniezu. The shogunate basically told every regional lord (the daimyo): "Hey, draw us a map of your land. Oh, and make it incredibly detailed, or we'll assume you're hiding something."

Imagine the stress.

You’ve got these samurai-turned-bureaucrats measuring coastline with nothing but ropes and compasses. They weren't using GPS. They were using Inō Tadataka’s methods before Inō Tadataka was even born. Well, mostly. Inō came later and walked the entire perimeter of Japan to create the first "scientific" map, but the early Edo maps were more about power than precision.

They used colors.

Yellow for roads. Blue for water. White for castle grounds. If you look at an original Shoho Kuniezu (around 1644), it’s a vibrant, colorful thing. It looks like art, but it’s really a tax document. It told the Shogun exactly how much rice—measured in koku—each province could produce. More rice meant more taxes and more potential for rebellion.

Why Tokyo (Edo) Looks So Weird

If you've ever gotten lost in Tokyo, blame the 17th century.

📖 Related: The Betta Fish in Vase with Plant Setup: Why Your Fish Is Probably Miserable

The central map of Japan Edo wasn't just a guide; it was a blueprint for a fortress. The city was built in a spiral around Edo Castle. This wasn't for aesthetics. It was a defense mechanism. If an invading army showed up, they’d get funnelled into these narrow, winding streets where they could be picked off by archers.

The Social Geography of the Map

Geography was destiny.

- The High Ground: The Yamanote (mountain hand) was where the wealthy samurai lived. It was breezy, safe from floods, and strategically superior.

- The Low Ground: The Shitamachi (lower town) was for the merchants and artisans. It was muddy, prone to fire, and crowded.

- The Outcasts: Certain groups were literally mapped out of existence or pushed to the very edges, near execution grounds or tanneries.

When you look at an Edo-era map, you notice that the samurai estates are huge. They take up like 70% of the city's land area, even though they were a minority of the population. The commoners—the people actually making the city run—were squeezed into tiny slivers of land.

It’s wild how much of this still exists.

The Imperial Palace in Tokyo occupies the exact same footprint as the old Edo Castle. The high-end neighborhoods like Akasaka and Azabu? Those were all samurai estates. The narrow, frantic streets of Nihonbashi? That was the merchant heart. The map of Japan Edo is basically a ghost image under the modern pavement.

Inō Tadataka: The Man Who Walked Japan

We have to talk about Inō Tadataka. He’s a legend in Japanese cartography. Most people retire and take up gardening. Inō retired at 49 and decided he was going to map the entire country by walking it.

He spent 17 years on the road.

He didn't just "walk." He measured. He used astronomical observations and incredibly precise surveying tools. His map, finished in 1821, was so accurate that when the British Navy showed up decades later with their fancy modern equipment, they realized they couldn't do a better job than he had.

The Dainihon Enkai Yochi Zenzu (Map of Japan's Coastal Areas) was a game-changer. For the first time, Japan knew its own shape. It wasn't just a collection of feudal estates anymore; it was a sovereign nation with clear borders.

👉 See also: Why the Siege of Vienna 1683 Still Echoes in European History Today

The "Illustrated" Vibe of Edo Maps

The thing about a map of Japan Edo is that it’s often "pictorial."

It’s not just lines. You’ll see little drawings of mountains, tiny people walking on the Tokaido road, and even mythical creatures in the sea. This style is called e-zu. It’s part map, part painting.

Take the Tokaido road maps. The Tokaido was the highway connecting Edo (Tokyo) to Kyoto. Maps of this road were like the 19th-century version of Tripadvisor. They’d show you where the best rest stops were, which temples had the coolest views, and where you could get the best mochi.

People didn't just use these maps to get from point A to point B. They used them to dream about travel. During the mid-Edo period, pilgrimages to Ise Grand Shrine became a huge fad. Everyone wanted to go. If you couldn't afford the trip, you bought a map and "traveled" with your eyes.

Misconceptions About Edo Cartography

People often think these maps were "primitive" because they don't look like Google Maps. That's a mistake.

They were specialized.

If a map was for a fireman, it highlighted water sources and narrow alleys where a fire could jump. If it was for a merchant, it highlighted the canals. If it was for a tourist, it highlighted the "famous places" (meisho). They weren't trying to be "accurate" in a mathematical sense; they were trying to be useful.

Also, there's this idea that Japan was "closed" (sakoku) and therefore didn't know about the rest of the world. Not true.

The shogunate had access to Dutch maps. They knew exactly where Europe and the Americas were. They just didn't want the general public to have that information. Control the map, control the narrative.

✨ Don't miss: Why the Blue Jordan 13 Retro Still Dominates the Streets

How to Read an Edo Map Today

If you're lucky enough to see an original woodblock print of an Edo map, here is what you should look for:

- Orient yourself: Many Edo maps weren't oriented North-at-the-top. Often, they were oriented toward the "center" of power—Edo Castle—or toward a major landmark like Mount Fuji.

- Look for the "Gokaiso": These were the official government checkpoints. On a map, they represent the tightening grip of the law.

- Check the Crests: Samurai estates are often marked by their family crest (mon). If you see a lot of hollyhock crests, you're looking at land owned by the Tokugawa family.

- Distortion: Distance often isn't literal. Important places are drawn larger. It’s "psychological geography."

Why This Matters Now

Why do we care about a map of Japan Edo in 2026?

Because you can't understand modern Japan without it. The "pockets" of culture in Tokyo exist because of these old boundaries. The reason some subway lines are so incredibly deep underground is because they have to weave around the massive foundation stones of old samurai gates and castle walls that show up on these maps.

History isn't just in books. It’s in the dirt.

If you want to experience this yourself, there are a few things you can actually do. You don't have to be a historian.

Actionable Steps for the Curious

- Use the "Edo-Tokyo" Layer: Apps like 7000 Steps or specialized map overlays allow you to walk through modern Tokyo while seeing the Edo map on your screen. It’s a surreal experience. You’ll be standing in front of a Starbucks and realize you’re actually standing in the middle of a Daimyo's former reception hall.

- Visit the Edo-Tokyo Museum: (Keep in mind it has been under renovation, so check current status). They have massive 1:1 scale replicas of Edo life and incredible cartography exhibits.

- Look at the crests: When walking around the Imperial Palace, look at the stone walls. You can still see the masons' marks—little symbols carved into the rock by different clans to prove they did their share of the work. This is the "map" in physical form.

- Compare the rivers: Many of the canals on an Edo map are now covered by highways (like the Shuto Expressway). If you look at a map of the highway system, you're basically looking at a map of Edo’s old water transport network.

The map of Japan Edo isn't a dead document. It's a living guide to how power, people, and the land interacted to create one of the most complex societies in human history. Whether you're a history nerd or just someone who likes a good story, these maps are the key to unlocking the real Japan.

Next time you’re in Tokyo, don’t just look at the skyscrapers. Look at the curve of the street. Chances are, that curve was put there 400 years ago to stop a samurai from getting a clear shot at a gate. That's the real magic of the map.

Further Research and Real Sources

For those who want to get deep into the weeds, look up the work of Mary Elizabeth Berry. Her book Japan in Print: Information and Nation in the Early Modern Period is the gold standard for understanding how maps changed Japanese society. You can also browse the National Archives of Japan digital collection. They have high-resolution scans of the Kuniezu that are absolutely stunning.

Also, check out the University of California, Berkeley East Asian Library. They have a massive digital collection of Edo-era maps that you can zoom in on until you see the individual brushstrokes. It's much better than just reading about it; you have to see the detail to believe it.

The transition from the artistic, subjective maps of the early 1600s to the cold, hard data of Inō Tadataka's 1821 map tells the story of Japan's modernization. It’s the story of a country becoming a nation. And it's all right there on the paper.