Look at a map of India and Sri Lanka. At first glance, it looks like a teardrop falling from a massive, triangular face. Simple. You see the vastness of the Indian subcontinent and that little island tucked just off the southeast coast of Tamil Nadu. But if you actually zoom in—like, really get into the weeds of the Palk Strait—the geography starts getting weird. It’s not just a gap of water. It’s a messy, beautiful, and politically charged stretch of sandbanks, coral reefs, and history that defies the clean lines you see on a standard wall map.

Most people think of these two countries as totally separate entities. Geographically, though? They were joined. Not even that long ago in geological terms.

The Bridge That Isn't There (But Sorta Is)

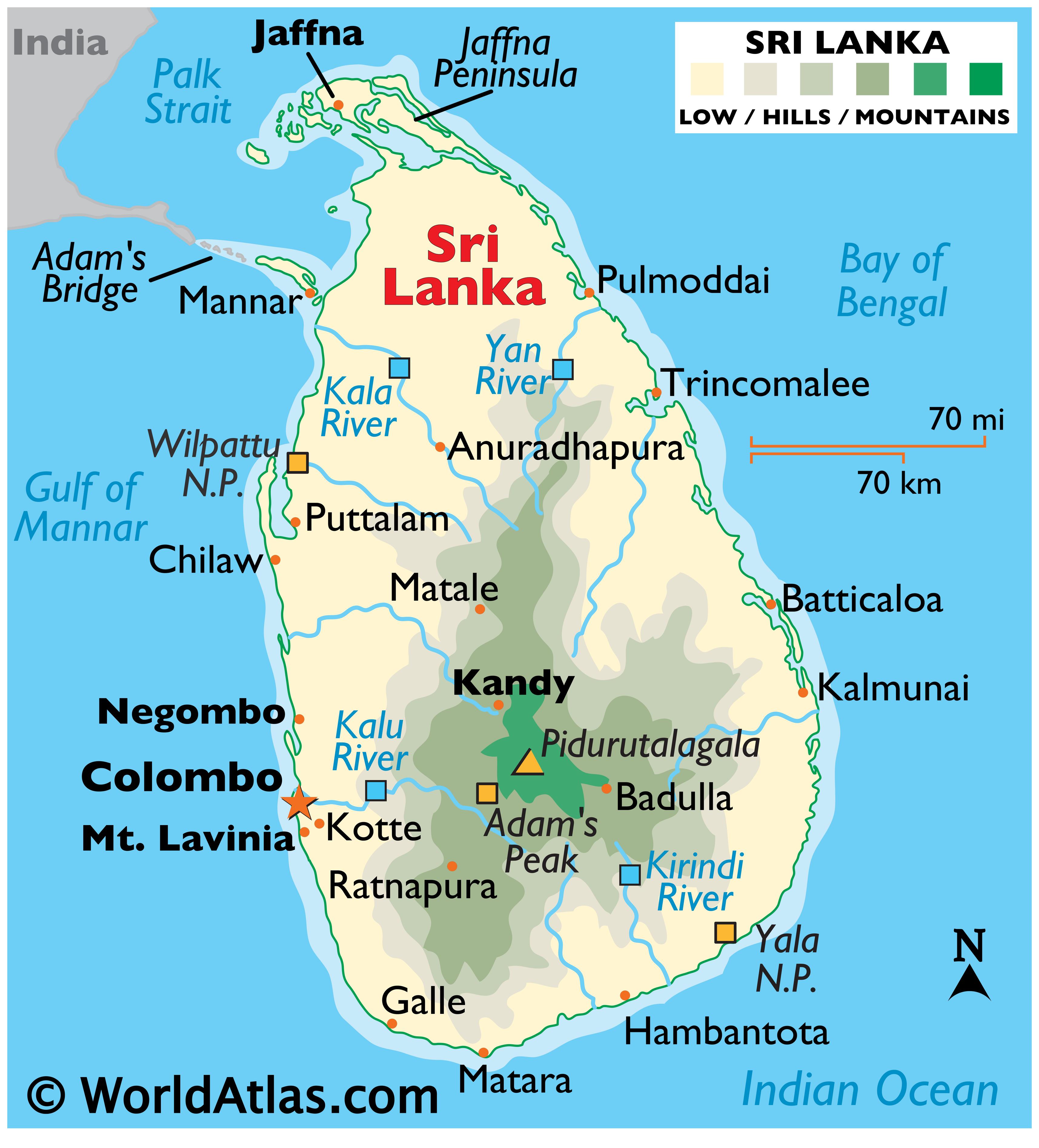

When you pull up a high-resolution map of India and Sri Lanka, your eyes are immediately drawn to that string of limestone shoals connecting Rameshwaram to Mannar Island. This is Rama’s Bridge, or Adam’s Bridge.

It’s about 48 kilometers long.

Honestly, it’s one of the most debated strips of land (well, submerged land) on the planet. Some records, including temple inscriptions, suggest that it was actually walkable until a massive cyclone in 1480 breached the path. Think about that. Less than 600 years ago, you could have potentially walked from India to Sri Lanka without getting your hair wet. Today, the water there is incredibly shallow, sometimes only a meter or two deep, which makes it a nightmare for large ships but a goldmine for satellite photography enthusiasts.

NASA images show this formation so clearly it almost looks artificial. This has led to endless debates between geologists and historians. Some say it's a natural process of crustal thinning and sand deposition. Others point to the Ramayana. Regardless of what you believe, the map tells a story of a connection that refuses to stay buried under the sea.

The Palk Strait Paradox

The water between the two is the Palk Strait. It’s narrow. It's also remarkably difficult to navigate. Because the water is so shallow around Adam's Bridge, big cargo ships can't just sail through the gap between India and Sri Lanka. They have to go all the way around the island of Sri Lanka to get from the Bay of Bengal to the Arabian Sea.

This brings us to the Sethusamudram Shipping Canal Project.

This has been a massive point of contention in Indian politics and environmental circles for decades. The idea was to dredge a deep channel through the shoals so ships could save hundreds of miles. But it’s not just a logistics issue. You have environmentalists worried about the fragile marine ecosystem and religious groups protecting what they see as a sacred monument. The map isn't just lines; it’s a battleground for identity.

✨ Don't miss: How Long Ago Did the Titanic Sink? The Real Timeline of History's Most Famous Shipwreck

Beyond the Coastline: The Topographical Shift

If you move your eyes north into the heart of India, the map is dominated by the Deccan Plateau and the massive river systems of the Ganges and Brahmaputra. But Sri Lanka is a different beast entirely. It’s often called the "Pearl of the Indian Ocean," but "The Granite Teardrop" might be more accurate if you’re looking at the rock.

The central highlands of Sri Lanka rise up like a fortress.

Compare that to the flat, coastal plains of Tamil Nadu just across the water. While India has the Himalayas—the literal roof of the world—Sri Lanka’s mountains like Pidurutalagala or the famous Adam's Peak (Sri Pada) provide a dramatic verticality that defines the island’s climate.

- The Indian side: Generally drier in the south, leaning heavily on the Kaveri River.

- The Sri Lankan side: The wet zone in the southwest gets hammered by the monsoon, creating lush rainforests that look nothing like the scrublands of southern India.

It’s wild how thirty miles of water can create such a distinct shift in biodiversity. You’ve got elephants on both sides, sure, but the Sri Lankan elephant is a distinct subspecies (Elephas maximus maximus). It’s larger and darker than its cousins on the mainland. The map separates them, and evolution did the rest.

The Geopolitical Tension of Tiny Islands

Look closely at the map of India and Sri Lanka in the Palk Bay, and you might spot a tiny speck called Kachchatheevu.

It’s a 285-acre uninhabited island.

You’d think nobody would care about a barren rock with no fresh water. You’d be wrong. In 1974, India ceded the island to Sri Lanka under the Indo-Sri Lankan Maritime Agreement. Today, it’s a massive flashpoint for fishermen in Tamil Nadu. The maps used by the Indian Coast Guard and the Sri Lankan Navy are the same, but the way they enforce them is where the trouble starts.

Indian fishermen, following traditional fishing grounds, often cross that invisible line on the map. Sri Lankan authorities arrest them. It’s a recurring cycle of diplomatic headaches. When you look at the map, that line looks so definitive. On the water, with the wind blowing and the nets out, it’s invisible.

🔗 Read more: Why the Newport Back Bay Science Center is the Best Kept Secret in Orange County

Maritime Boundaries and the Exclusive Economic Zone

The maritime boundary between India and Sri Lanka is unique because it’s a "delimited" boundary settled by bilateral agreements in the 70s. Unlike many other international borders where countries argue over where the line falls, India and Sri Lanka actually have a pretty clear-cut legal map.

But "clear-cut" doesn't mean "simple."

The Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) of both countries overlaps significantly. If you were to draw a 200-nautical-mile circle around each country, they’d be on top of each other. This forced both nations to come to a compromise, creating a median line that zig-zags through the ocean.

This geography makes the region a "choke point" for maritime security. With China’s increasing presence in the Indian Ocean—specifically their 99-year lease on the Hambantota Port in southern Sri Lanka—the map has become a game of regional chess. New Delhi looks at the map and sees a strategic necessity. Colombo looks at the map and sees a way to leverage its position for economic gain.

What the Maps Don't Tell You About Connectivity

We talk about the map of India and Sri Lanka as if it's static. It’s not.

There are serious, high-level discussions happening right now about building a physical land bridge. Not a sandbar, but a modern rail and road link. The Asian Development Bank has looked into the feasibility of this. Imagine driving from Chennai to Colombo. It would fundamentally change the economy of South Asia.

Currently, the most common way between the two is a short flight from Chennai to Colombo, which takes barely an hour. Or the ferry services, which have been started and stopped more times than I can count. The geography says they should be deeply integrated, but the politics of the last 50 years—including the Sri Lankan Civil War—kept the map "closed" for a long time.

Now, the map is opening up.

💡 You might also like: Flights from San Diego to New Jersey: What Most People Get Wrong

Navigating the Map: Practical Insights for Travelers and Researchers

If you're looking at a map of India and Sri Lanka to plan a trip or do research, don't trust the scale to tell the whole story.

- Transport isn't linear. You can’t just "hop across" from Rameshwaram to Mannar. You have to fly or take a ferry (when they are running). The proximity is a bit of a tease.

- Cultural Geography. The northern part of Sri Lanka (Jaffna) has more in common culturally and linguistically with Tamil Nadu than it does with southern Sri Lanka. The map shows a political divide, but the cultural map is a gradient.

- Climate zones. Don't assume the weather in Madurai is what you'll find in Kandy. Sri Lanka's elevation changes create microclimates that are far more temperate than the scorching heat of the South Indian plains.

Understanding the Cartographic History

Old colonial maps from the British Raj show a much more unified vision of the region. Back then, both were under British influence, though administered differently. The maps from the 1800s often highlighted the "pearl fisheries" of the Gulf of Mannar, which were world-famous.

Today’s maps focus on "sovereignty" and "security." You see naval bases marked. You see "No Fire Zones" and "Fisheries Management Areas." The map has transitioned from a document of discovery to a document of management.

When you study the map of India and Sri Lanka, you aren't just looking at landmasses. You’re looking at a relationship that is thousands of years old, bound by a submerged bridge and separated by a narrow strip of water that everyone wants to control.

Actionable Next Steps for Mapping This Region

If you are a traveler, student, or researcher, here is how you should actually approach this geography:

First, use OpenStreetMap (OSM) instead of just Google Maps if you want to see the intricate details of the Adam's Bridge shoals; the community-driven data often captures the shifting sandbars better. Second, if you're planning a journey between the two, check the current status of the Nagapattinam-Kankesanthurai ferry service. It’s the most "geographically authentic" way to cross, but it is notoriously seasonal and subject to diplomatic whims. Finally, look into the Gulf of Mannar Marine Biosphere Reserve. It covers the Indian side of the map and is one of the richest coastal regions in all of Asia—don't just look at the lines, look at the life between them.

The gap between India and Sri Lanka is only about 18 miles at its narrowest point, but there’s an entire world of history and tension packed into those few miles of blue.