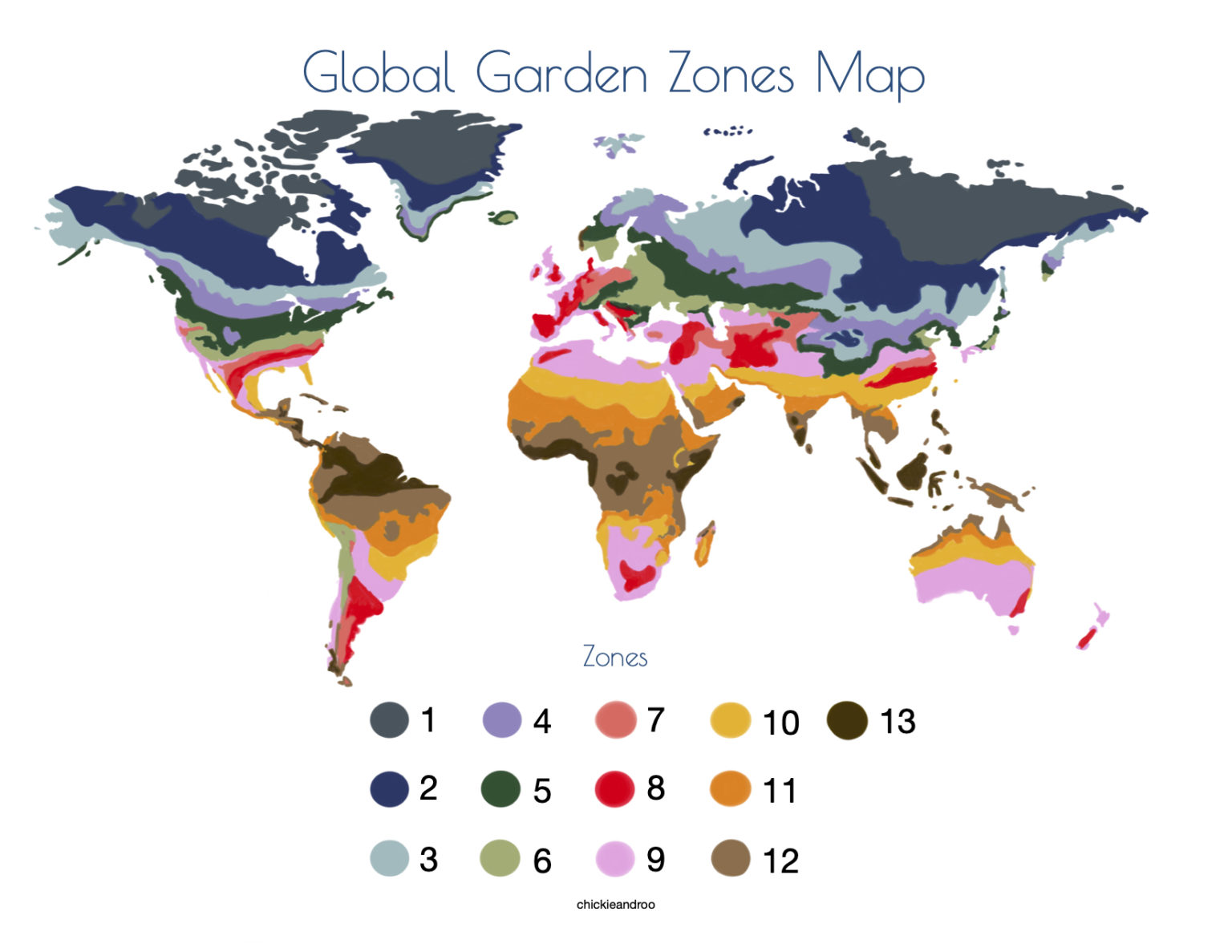

You’ve probably seen the colorful, jagged lines. Maybe you’ve squinted at a seed packet in the hardware store aisle, trying to figure out if your backyard is a 6b or a 7a. That map of garden zones—specifically the USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map—is basically the Bible for anyone trying to keep a perennial alive through the winter. But here is the thing: it isn’t a guarantee. It’s a historical average. And lately, those averages are shifting in ways that make old-school gardening advice feel a little bit like using a flip phone in 2026.

Last time the USDA dropped a major update, millions of gardeners woke up to find they’d been "moved." You didn't move your house, obviously. The climate moved under you.

What the Map of Garden Zones Actually Tells You (and What it Doesn't)

Most people think the map is a weather forecast. It isn’t.

Basically, the map is based on the "average annual extreme minimum winter temperature." That is a mouthful. What it really means is: how cold does it usually get on the single worst night of the year? If you live in Zone 8, you can expect the mercury to dip between 10°F and 20°F. If you're in Zone 3, you're looking at a bone-chilling -40°F.

But here’s the kicker. The map doesn't care about your blistering July heat. It doesn't care about humidity, soil pH, or whether you get 50 inches of rain or five. You could be in Zone 7 in the high desert of New Mexico or Zone 7 in the soggy woods of New Jersey. The plants that thrive in one will absolutely kick the bucket in the other. This is where people get tripped up. They buy a "Zone 7" lavender plant in Albuquerque and wonder why it rots in the humidity of Trenton.

Context matters.

The 2023 Shift and the Reality of 2026

The USDA updated the map recently using data from over 13,000 weather stations. It was a massive undertaking. The result? About half the United States shifted into a warmer half-zone.

That might not sound like a big deal. It’s just five degrees, right? Tell that to a fig tree. For a lot of gardeners in the Mid-Atlantic and the Midwest, that shift meant they could suddenly experiment with plants that used to be "marginal." We're talking about Southern Magnolias blooming in places they never used to survive.

🔗 Read more: God Willing and the Creek Don't Rise: The True Story Behind the Phrase Most People Get Wrong

But there’s a catch.

While the average low is getting warmer, the volatility is increasing. We’re seeing more "flash freezes." This is when it stays a balmy 60°F until December, your plants don't go dormant properly, and then a polar vortex slams the temperature down to 0°F in six hours. The map of garden zones says you're safe, but the erratic weather says otherwise.

Microclimates: Why Your Backyard is Different from Your Neighbor's

You can't just look at a national map and call it a day. Honestly, your specific yard probably has its own zip code when it comes to temperature.

I’ve seen gardens where the front yard is a Zone 7 but the backyard—tucked behind a brick wall that soaks up afternoon sun—acts like a Zone 8. That brick wall is a "heat sink." It radiates warmth all night. On the flip side, if your garden is at the bottom of a hill, you’re in a "frost pocket." Cold air is heavy. It sinks. While your neighbor up the hill is still enjoying their dahlias, yours might be black mush after the first light frost.

Think about these things:

- Pavement and Concrete: Driveways and sidewalks hold heat. Great for zone-pushing, bad for plants that need a long winter nap.

- Wind Exposure: A bitter north wind can drop the "real feel" for a plant significantly, desiccating evergreen leaves even if the air temperature is technically within the safe zone.

- Canopy Cover: Large trees act like a blanket, trapping ground heat.

The Trouble with "Zone Pushing"

We all do it. We see a plant rated for one zone warmer than ours and we think, "I can make this work."

It’s a gamble. Sometimes you win for five years. Then, a "100-year freeze" comes along and wipes out your entire landscape. Expert horticulturists like Tony Avent from Plant Delights Nursery often talk about this. They test the limits of the map of garden zones constantly. The lesson is usually: if you’re going to push the zone, don’t make that plant the "anchor" of your garden.

💡 You might also like: Kiko Japanese Restaurant Plantation: Why This Local Spot Still Wins the Sushi Game

Don't plant a Zone 8 tree as the centerpiece of a Zone 7 yard. Use it as an accent. That way, if the "Big One" hits and the plant dies, your whole landscape doesn't look like a construction site.

Soil is the Great Equalizer

Here is a secret most "big box" garden centers won't tell you. A plant's hardiness is directly tied to how wet its feet are in the winter.

If you have heavy clay soil that stays soggy, a plant that is "hardy to Zone 6" might die in Zone 7. Why? Because the roots freeze in a block of ice. If you have well-draining, sandy soil, that same plant might survive a Zone 5 winter. When you look at your map of garden zones, you have to overlay that information with your soil type.

Drainage is life.

Beyond the USDA: Heat Zones and Sunset Zones

If you live in the Western United States, the USDA map is... okay. But it’s not great.

The American Horticultural Society (AHS) created a "Heat Zone Map." This tracks how many days per year the temperature goes above 86°F. This is the point where many plants start to suffer from heat stress. For gardeners in Georgia or Texas, the heat zone is often more important than the cold zone.

Then there’s the Sunset Western Garden Book. For people in California, Oregon, or Washington, this is the gold standard. They break the West down into 45 distinct zones. They account for mountains, ocean influence, and the weird way the Pacific fogs up the coast. If you’re trying to grow a garden in Seattle using only the USDA map of garden zones, you’re doing it on hard mode.

📖 Related: Green Emerald Day Massage: Why Your Body Actually Needs This Specific Therapy

Practical Steps for Your Garden This Season

Stop treating the map like a rulebook. Treat it like a suggestion.

First, go to the USDA website and type in your exact zip code. Don't just look at the state map; the new high-resolution versions can show variations down to a few miles.

Next, track your own data. Buy a cheap high-low thermometer. Stick it in the spot where you actually want to plant. You might be surprised to find your yard is consistently 4 degrees colder than the local airport where the official data is collected.

Third, look at what’s thriving in your older neighbors' yards. If they have a 30-year-old Camellia, you know that your area hasn't seen a "killer freeze" for that specific species in three decades. That is better data than any map can give you.

Finally, when you're at the nursery, look at the tags. But then, pull out your phone. Search for the plant name plus "winter hardiness trials." Universities like Penn State or NC State often run trials where they actually try to kill these plants to see how much they can take.

Actionable Takeaways

- Mulch early and deep: If you're worried about your zone, 3-4 inches of wood chips or leaves can keep the ground from freezing as deeply, effectively "insulating" your plant's roots.

- Water before a freeze: Dry soil freezes faster and deeper than moist soil. If a cold snap is coming, give your perennials a good soak.

- Use burlap, not plastic: If you’re covering a plant that’s on the edge of its zone, burlap allows it to breathe. Plastic can actually "cook" the plant if the sun comes out the next morning.

- Plant late, prune late: In shifting zones, wait until late spring to prune back "dead" looking wood. Sometimes, the plant is just waiting for the soil to truly warm up.

The map of garden zones is an evolving document. It's a snapshot of a changing world. Use it as a starting point, but trust your shovel and your own observations more than a colored line on a screen. Gardening is local. Your backyard is the only map that truly matters.