California is basically a giant jigsaw puzzle that doesn't quite fit together. Most people living here know the big names—San Andreas, obviously—but if you actually look at a map of fault lines in California, it looks like someone spilled a bowl of cracked spaghetti across the state. It’s messy. It’s everywhere. And honestly, it’s the reason our landscape is so breathtakingly beautiful and simultaneously nerve-wracking.

We live on a tectonic plate boundary. That sounds clinical, but it means the ground beneath your favorite coffee shop in Silver Lake or that tech campus in Mountain View is literally grinding past itself at about the same rate your fingernails grow. Over millions of years, that "fingernail growth" adds up to the Sierra Nevada mountains and the jagged coastline of Big Sur. But in the short term? It leads to the "Big One" everyone talks about at dinner parties.

Reading the Map of Fault Lines in California Like a Local

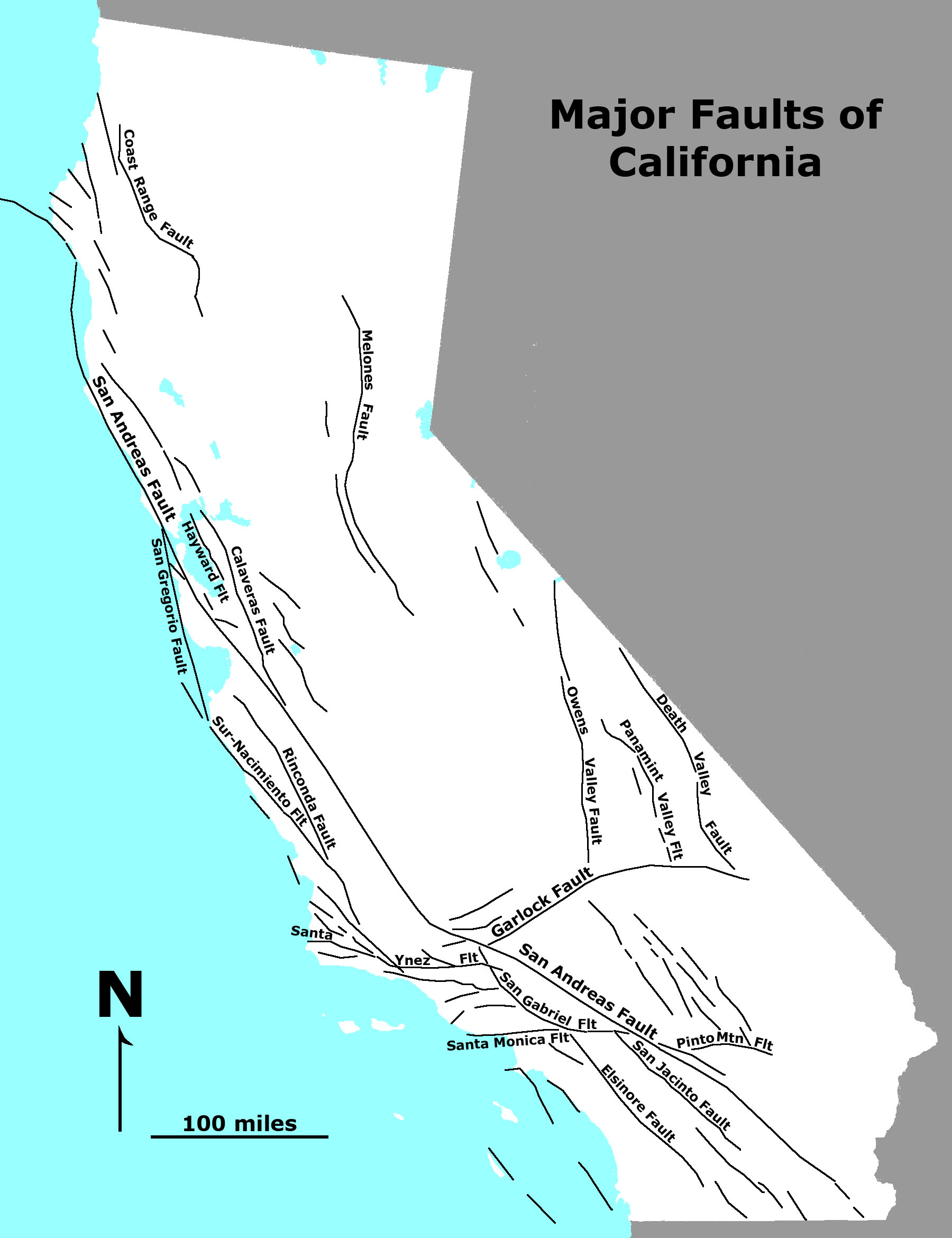

If you pull up a detailed map of fault lines in California from the California Geological Survey (CGS), the first thing you notice isn't just one line. It’s a network. The San Andreas Fault is the backbone, stretching roughly 800 miles from the Salton Sea up to Cape Mendocino. It’s a strike-slip fault, meaning the Pacific Plate and the North American Plate are sliding horizontally past each other.

But here is the thing: the San Andreas isn't just one crack. It has "splays."

Think of it like a freeway. You have the I-5, which is the main artery, but then you have all these off-ramps and parallel routes like the 405 or the 101. In the Bay Area, the Hayward Fault and the Calaveras Fault are those "parallel routes." They actually carry a huge chunk of the tectonic "traffic." The Hayward Fault is particularly nasty because it runs directly through densely populated areas like Berkeley and Hayward. It literally cuts through the University of California, Berkeley's Memorial Stadium. They had to build the stadium in two separate halves so the walls could slide past each other without collapsing the whole structure during an earthquake. That is peak California engineering.

Down south, the situation is even more complex. You’ve got the San Jacinto Fault, which is actually more seismically active than the San Andreas in some spots. Then there’s the Newport-Inglewood fault, which caused the 1933 Long Beach quake. If you look at the map of fault lines in California for the Los Angeles Basin, it’s a spiderweb. We have "blind thrust" faults too. These are the ones that don't even break the surface. You can't see them on a hike. You only know they're there when the ground starts jumping, like it did during the 1994 Northridge earthquake.

The Mystery of the "Garlock" and the "Eastern California Shear Zone"

Not all faults run north-south. The Garlock Fault is a weird one. It runs east-west across the Mojave Desert. It’s like a giant cross-stitch holding the state together, or maybe pulling it apart. Geologists get really excited about the Garlock because it marks a major transition in how the crust is moving.

Lately, there’s been a lot of talk about the Eastern California Shear Zone. Remember the Ridgecrest earthquakes in 2019? Those happened out in the desert, away from the "famous" faults. It was a reminder that the map of fault lines in California is constantly being updated. We are discovering new faults all the time because, well, the earth is literally breaking under our feet in ways we didn't expect. Those Ridgecrest quakes actually "unzipped" two different faults that crossed each other at right angles. Nobody really had that on their 2019 bingo card.

💡 You might also like: Human DNA Found in Hot Dogs: What Really Happened and Why You Shouldn’t Panic

Why the "Big One" Isn't Just One Thing

When people search for a map of fault lines in California, they're usually looking for peace of mind. They want to know if their house is on a red line. But the truth is, the "Big One" is a bit of a misnomer.

There isn't just one "Big One."

A massive M7.8 rupture on the southern San Andreas is the classic nightmare scenario. It would start near the Mexican border and unzip all the way up to Lake Hughes. The shaking could last for two minutes. Two minutes is a very, very long time when your house is vibrating. But we could also have a "Big One" on the Hayward Fault, or a massive offshore quake on the Cascadia Subduction Zone up north near Eureka.

The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) uses a model called UCERF3 to predict these things. It’s basically a massive statistical engine that says there’s a nearly 100% chance of a M6.7 or greater earthquake somewhere in California in the next 30 years. It’s not a matter of "if," just "where." And "where" is usually somewhere on that crowded map.

Blind Thrust Faults: The Hidden Danger

Let's talk about the 1994 Northridge earthquake for a second. That quake didn't happen on the San Andreas. It happened on a fault no one knew existed. It was a "blind thrust" fault, meaning it’s buried deep underground and doesn't reach the surface. This is why just looking at a map of fault lines in California isn't enough. You have to account for the stuff you can't see.

The Los Angeles basin is sitting on a deep pile of soft sediment—basically a giant bowl of jelly. When an earthquake hits, those seismic waves get trapped in the sediment and bounce around. It amplifies the shaking. So even if you aren't directly on a fault line, if you're in a "basin," you're going to feel it way more than someone sitting on solid granite in the mountains.

Real-World Consequences of Living on the Line

So, what does this actually mean for you?

📖 Related: The Gospel of Matthew: What Most People Get Wrong About the First Book of the New Testament

First, there’s the Alquist-Priolo Earthquake Fault Zoning Act. This is a California law passed after the 1971 San Fernando earthquake. It basically says you can't build a house directly on top of an active fault trace. If you’re buying a home, your natural hazard disclosure report will tell you if you're in one of these zones.

If you are? You might have trouble getting insurance. Or your premiums will be through the roof.

Then there’s the "soft story" issue. You know those apartment buildings with tuck-under parking on the first floor? Those are incredibly vulnerable. During the Northridge quake, many of them just pancaked. Cities like LA and San Francisco have been forcing landlords to retrofit these buildings, which is great for safety but can be a headache for renters and owners.

How to Actually Use a Fault Map

Don't just look at a static image on Google Images. Go to the source.

- USGS Quaternary Fault and Fold Database: This is the gold standard. It’s an interactive map where you can zoom in down to your neighborhood.

- MyHazards (Cal OES): You can plug in your address and it will tell you your risk for quakes, floods, and fires.

- CGS Information Warehouse: This is where you find the official regulatory maps that affect property values and building codes.

When you look at these, pay attention to the "age" of the fault. A "Holocene" fault has moved in the last 11,000 years. Those are the ones we worry about most. "Late Quaternary" moved in the last 130,000 years. Still a threat, but maybe not as "active" in human terms.

The Surprise of the "Creeping" Faults

Most faults stay "locked." They build up stress for 100 or 200 years and then—snap—earthquake. But some parts of the map of fault lines in California show "creeping" faults.

The San Andreas near Hollister is a famous example. It’s moving slowly but surely, all the time. It doesn't build up as much stress because it’s constantly releasing it. You can walk around the town of Hollister and see curbs that are offset by several inches and sidewalks that look like they’ve been pulled apart. It’s a slow-motion disaster that isn't actually a disaster because it’s not creating a huge jolt. It's just... moving.

👉 See also: God Willing and the Creek Don't Rise: The True Story Behind the Phrase Most People Get Wrong

Practical Steps to Take Right Now

You can't move the faults. They were here long before us and they'll be here long after. But you can change how you live with them.

First off, secure your space. Most injuries in earthquakes aren't from buildings falling down; they're from "non-structural" stuff. TVs falling. Bookshelves toppling. Kitchen cabinets flying open. Go to the hardware store and buy some "earthquake putty" for your vases and some straps for your heavy furniture. It costs twenty bucks and takes an hour. Do it.

Second, check your water heater. It needs to be strapped to the wall studs. If a quake hits and your water heater tips over, it can break the gas line. That’s how fires start. And in a big quake, the fire department might not be able to get to you because the roads are cracked or blocked.

Third, get a "Go Bag." But don't just put some granola bars in it. You need water—a gallon per person per day. You need your meds. You need a physical map of your area because your phone might not have service if the towers are down.

Finally, download the MyShake app. It’s developed by UC Berkeley. It uses the sensors in your phone (and a network of professional sensors) to give you a few seconds of warning before the shaking starts. It’s not much, but ten seconds is enough to get under a sturdy table or drop, cover, and hold on.

Living in California is a trade-off. We get the weather, the mountains, and the culture, but we pay for it with tectonic instability. Understanding the map of fault lines in California isn't about living in fear. It’s about knowing the terrain. It’s about being smart enough to realize that the ground isn't as solid as it looks, and preparing accordingly.

Check your address on the USGS map today. Look for the nearest red line. Not to freak yourself out, but to know which direction the ground might move when the puzzle pieces finally decide to shift again. If you're in an older home, look into the "Earthquake Brace + Bolt" program; the state literally gives out grants to help people bolt their houses to their foundations. It’s one of the few times the government actually hands you cash to make your life safer. Take it.

Get your shoes under your bed. Keep a flashlight nearby. The map is just a guide, but your preparation is what actually matters when the map starts moving.