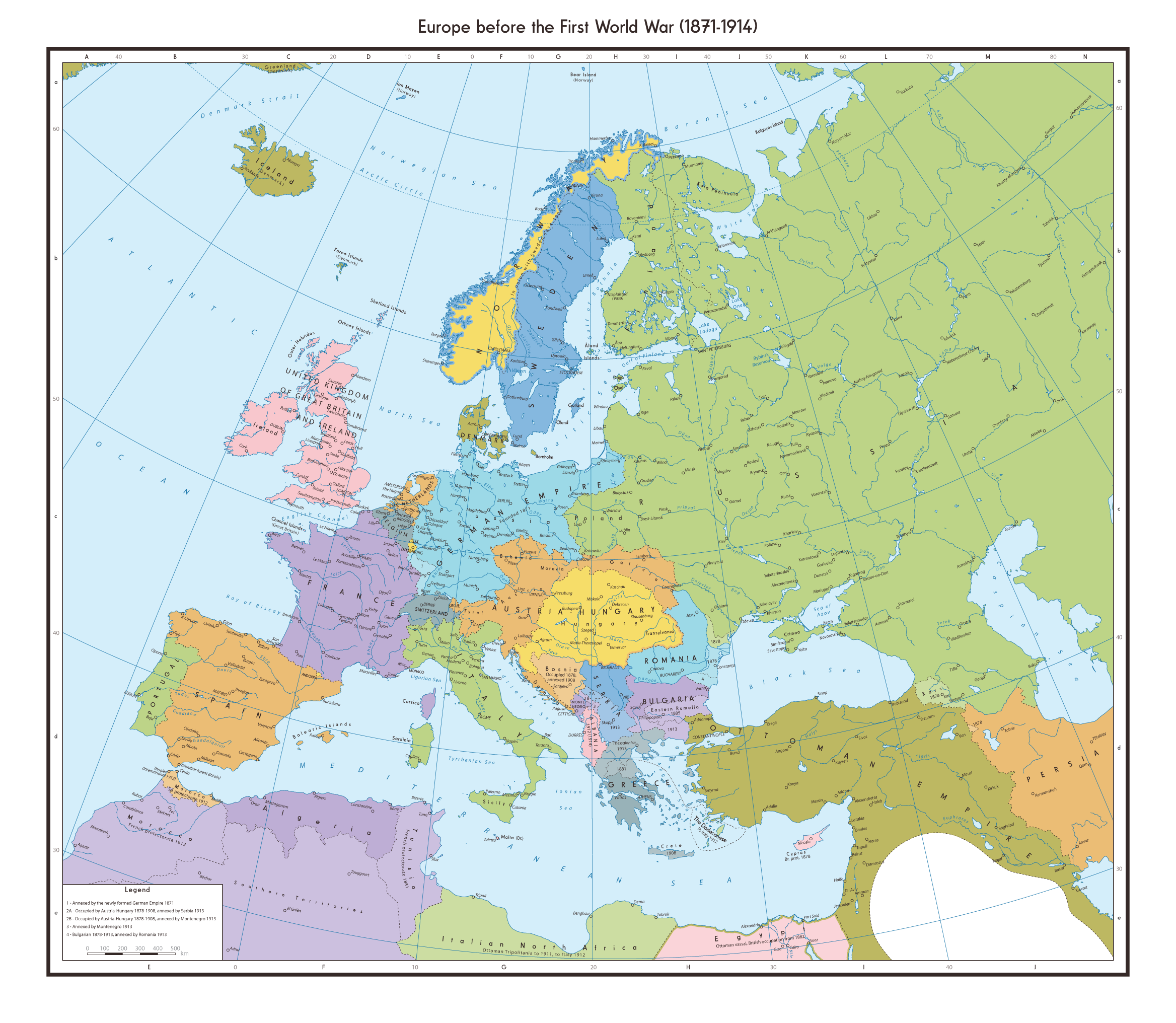

Look at a globe today. You see Poland. You see Ukraine. You see the Czech Republic. Now, squint and try to imagine those borders vanishing. That's the reality of 1914. If you actually sit down and stare at a map of europe in world war one, the first thing that hits you is how empty the east looks. It’s basically just three giant blocks of color crashing into each other. It’s weird. It feels like looking at a different planet where the landmasses are the same but the "owners" are all wrong.

The Great War wasn't just a meat grinder of men; it was a geographic eraser.

The Big Three (and why they didn't last)

Before the first shots were fired in Sarajevo, the map of europe in world war one was dominated by what historians like Margaret MacMillan often call the "Old World Order." You had the German Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and the Russian Empire. These weren't nations in the way we think of them now. They were multi-ethnic jigsaw puzzles held together by royal spit and glue.

Austria-Hungary was the craziest one. Honestly, looking at their internal borders is a headache. You had Germans, Magyars, Slavs, Italians, and Romanians all living under the Habsburg crown. When you see a 1914 map, Austria-Hungary looks like this massive, solid belly in the middle of the continent. But it was brittle. It was a "dual monarchy" that functioned about as well as a bicycle with square wheels.

Then there's Germany. In 1914, Germany was big. It stretched far into what is now modern-day Poland. The city we call Gdańsk today was Danzig then. Kaliningrad? That was Königsberg, the heart of East Prussia. The German Empire wasn't just a country; it was a European superpower that physically separated Russia from the rest of the West.

Russia, meanwhile, was a behemoth. It touched the Pacific on one side and the German border on the other. Finland wasn't its own thing yet; it was a Grand Duchy under the Tsar. Poland? Mostly a Russian province. When you look at the Eastern Front on a map of europe in world war one, you're looking at a space so vast that the trench warfare of the West was basically impossible. There was just too much room to run.

The Western Front: The Line That Wouldn't Move

If the East was about vast distances, the West was about a literal line in the dirt. On a map of europe in world war one, the Western Front looks like a jagged scar. It ran from the Swiss border all the way up to the North Sea.

People think the line moved a lot. It didn't.

📖 Related: Weather Forecast Lockport NY: Why Today’s Snow Isn’t Just Hype

For nearly four years, that line barely budged. You’d have a battle like the Somme where hundreds of thousands died for a gain of maybe six miles. On a standard map, that’s a fraction of an inch. It’s haunting to think about. The scale of the map versus the scale of the suffering is totally out of whack.

Belgium was the tragic center of this. Before the war, Belgium was supposed to be neutral. The "Scrap of Paper," as the Germans called the treaty. But look at a map: if you're Germany and you want to punch France in the face, you go through the flat lands of Belgium to avoid the French forts in the south. Geography dictated the crime.

The Sick Man and the Balkan Powder Keg

Down south, the map of europe in world war one gets even messier. The Ottoman Empire—often called "The Sick Man of Europe"—was still hanging on to bits of the Balkans, though they were losing ground fast.

The Balkans are where the map actually caused the war.

Serbia wanted to be the leader of a South Slav state. Austria-Hungary, which owned Bosnia (which Serbia wanted), said "absolutely not." When you look at a 1914 map of the Balkans, you see a cluster of small, angry states bordering a dying empire and an insecure one. It’s a recipe for disaster. The borders there were drawn with zero regard for who actually lived on the land.

- Serbia: Growing, ambitious, backed by Russia.

- Bulgaria: Mad about the last war, looking for a rematch.

- Greece: Trying to expand into Ottoman territory.

- Montenegro: Small but scrappy.

It was a nightmare of overlapping claims. Honestly, if you try to memorize the Balkan borders of 1912 vs 1914 vs 1919, you’ll go crazy. It’s a shifting sea of territorial ambition.

The Great Erasing: 1917 and the Collapse

The map of europe in world war one didn't just change at the end of the war. It started falling apart in 1917. Russia collapsed. The Bolsheviks took over and signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk.

👉 See also: Economics Related News Articles: What the 2026 Headlines Actually Mean for Your Wallet

This is a part of the map people usually ignore.

Under that treaty, Russia gave up a massive chunk of territory to Germany. For a brief moment in 1918, the German Empire reached deep into Ukraine and the Baltics. If Germany had won the war, the map of Europe today would look like a giant German blob with puppet states stretching to the Caucasus. It’s one of those "what if" scenarios that makes your skin crawl.

But they didn't win.

1919: The Mapmakers of Versailles

When the war ended, the "Big Four" (the US, UK, France, and Italy) sat down in Paris with a bunch of colored pencils and a lot of ego. They wanted to redraw the map of europe in world war one to ensure "national self-determination."

Sounds great on paper. In practice? A mess.

They created "The Polish Corridor" to give the new Poland access to the sea. But in doing so, they cut off East Prussia from the rest of Germany. They created Czechoslovakia, a country that had never existed, cramming Czechs and Slovaks (and a bunch of unhappy Germans) together. They created Yugoslavia, which was basically the Balkan tensions of 1914 but packaged as a single country.

The map of 1919 looks a lot more like the map we know, but it was built on shaky ground.

✨ Don't miss: Why a Man Hits Girl for Bullying Incidents Go Viral and What They Reveal About Our Breaking Point

Why You Should Care About These Old Borders

Geography is destiny. Or at least, it’s a very loud suggestion.

The reason we still study the map of europe in world war one isn't just for history buffs. It's because the ghosts of those borders are still there. When you see the current conflict in Ukraine, you’re seeing echoes of the collapse of the Russian and Austro-Hungarian empires. When you look at the tensions in the Balkans in the 1990s, you’re looking at the failure of the 1919 mapmakers.

These weren't just lines. They were walls. They were promises. And often, they were lies.

Understanding the Map: Actionable Steps for Deep Learners

If you really want to wrap your head around how the map of europe in world war one functioned, don't just look at a static image. You need to see the movement.

- Compare 1914 to 1923 side-by-side. Look specifically at the "Successor States." Notice how many new countries appear in the space where the Russian and Austro-Hungarian empires used to be. (Poland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia).

- Trace the "Pripet Marshes." Look at the border between Russia and the Central Powers. You’ll see a massive swampy area. Geography like this dictated where armies could move, creating two distinct theaters of war in the East.

- Check out the "Blue Line of the Vosges." This was the mountainous border between France and Germany. It’s why the fighting shifted toward the flat plains of Belgium. Geography forced the violation of Belgian neutrality.

- Use an Interactive Map. Sites like Omniatlas or the Imperial War Museum digital archives allow you to see the front lines move month by month. It turns a boring map into a living, breathing thing.

- Read "The Guns of August" by Barbara Tuchman. She explains the opening moves of the war through the lens of geography better than almost anyone else. It makes the map feel like a game of high-stakes chess.

The map of europe in world war one isn't a dead document. It’s a blueprint of the modern world. Every time you see a news report about a border dispute in Eastern Europe or a sovereignty movement in the UK, you’re seeing the ripples of 1914. We are still living in the wreckage of those four years.

Understanding the map is the only way to understand why the world looks the way it does now. It’s not just about where people were; it’s about where they thought they belonged. And usually, the mapmakers didn't agree.