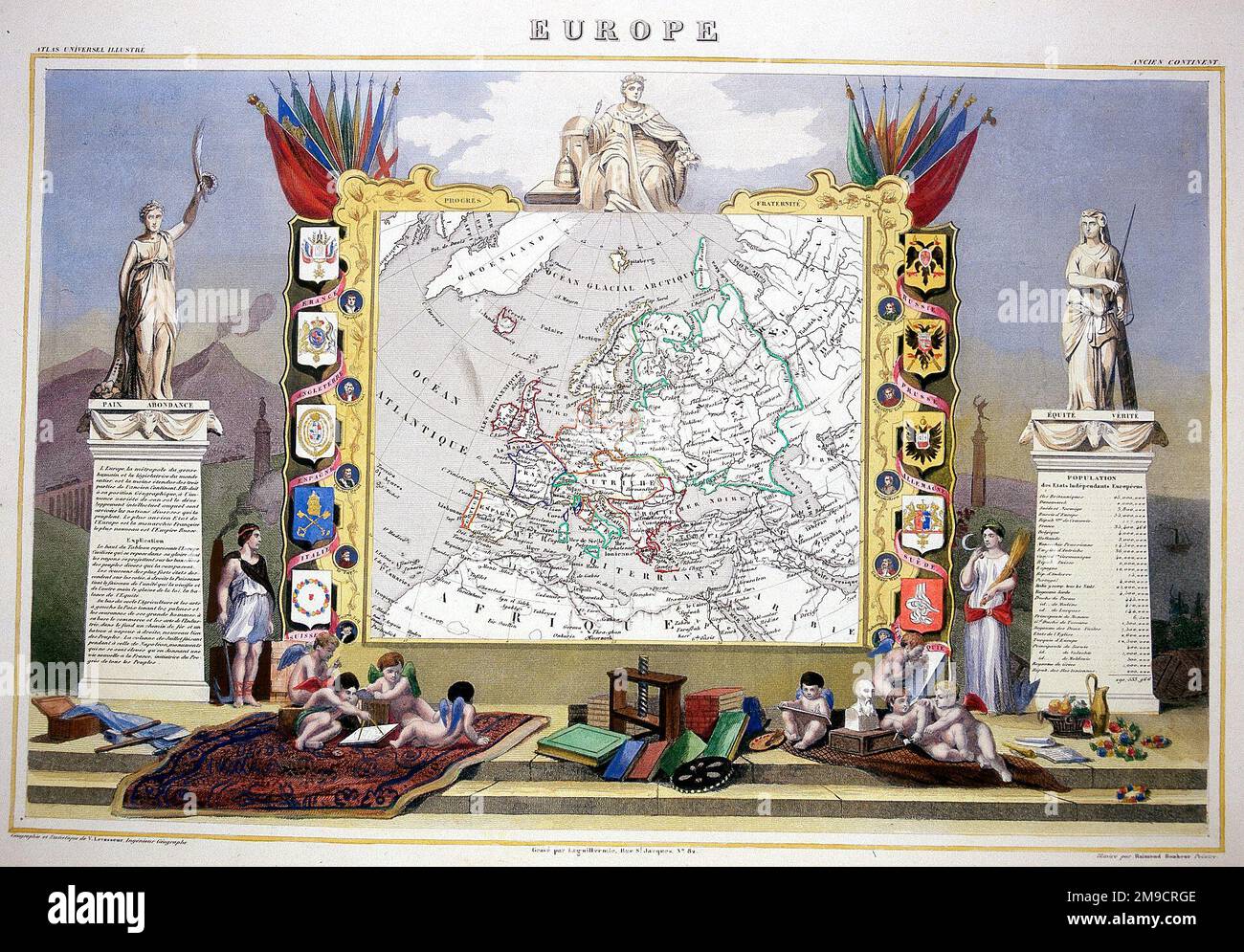

If you look at a map of Europe in the 19th century, you'll realize it doesn't look anything like the organized, neatly bordered continent we see on Google Maps today. It was chaotic. Think of it as a hundred-year-long game of Risk where the players kept changing the rules every ten minutes. At the start of the 1800s, Germany wasn't even a country. Italy was just a "geographical expression," as the Austrian diplomat Klemens von Metternich famously complained. By 1900, the board had been flipped.

Power shifted. Empires died. New nations screamed into existence.

Most people think history is a slow crawl toward progress, but 19th-century cartography was more like a series of violent jolts. You had the Napoleonic Wars literally redrawing every border from Spain to Russia before the century even hit its second decade. Napoleon had a habit of creating "sister republics" and then turning them into kingdoms for his brothers. When he finally fell at Waterloo in 1815, the big players—the "Great Powers"—sat down in Vienna to try and put the puzzle back together. But they didn't use the old pieces. They made new ones.

The Congress of Vienna: The Map That Tried to Stop Time

Imagine a room full of guys in powdered wigs and medals trying to pretend the French Revolution never happened. That was the Congress of Vienna. They wanted a map of Europe in the 19th century that favored "stability" over "people." This meant creating a "Buffer State" system. They gave the Netherlands a bunch of territory (which we now know as Belgium) just to keep France in check. They handed large chunks of Poland to Russia.

It was a balancing act.

The goal was simple: make sure no single country could ever pull a "Napoleon" again. But they ignored one massive thing—nationalism. People started realizing they didn't want to be ruled by some guy in a palace three hundred miles away who didn't even speak their language. This tension is why the 1815 map looks so different from the 1848 map. In 1848, a wave of revolutions swept the continent. It was the "Springtime of Nations." While most of those revolts technically failed, they cracked the foundation of the old empires. You can see it in the maps of the era; the borders stay the same, but the names of the provinces start to bubble with unrest.

Germany and Italy: The Great Filling of the Holes

For the first half of the century, the middle of Europe was basically a giant hole. Well, not a hole, but a patchwork. The Holy Roman Empire was gone, replaced by the German Confederation—a loose collection of 39 states. Prussia was the big bully in the north, and Austria was the refined, aging power in the south.

📖 Related: What Does a Stoner Mean? Why the Answer Is Changing in 2026

Then came Otto von Bismarck.

Bismarck didn't care about "liberal ideals" or "democracy." He cared about "Blood and Iron." Through three targeted wars against Denmark, Austria, and finally France in 1870, he forced the German states into a single Empire. Suddenly, the map of Europe in the 19th century had a massive, industrial powerhouse right in the center. This shifted the entire gravity of the continent.

Meanwhile, down south, Italy was doing its own thing. Or trying to.

Italy was a mess of kingdoms, duchies, and the Papal States (where the Pope was a literal king). Figures like Cavour, the diplomat, and Garibaldi, the guy with the red shirt and the sword, stitched it together. By 1871, Rome was the capital of a unified Italy. If you compare a map from 1850 to 1875, the change is staggering. The "patchwork" was replaced by two solid blocks of color.

The Dying Man of Europe and the Balkan Powderkeg

While the West was consolidating, the East was falling apart. The Ottoman Empire was nicknamed "The Dying Man of Europe." It held a massive amount of territory in the Balkans—Greece, Serbia, Bulgaria, Romania—but it couldn't hold on.

As the Ottomans receded, everyone else rushed in to grab a piece.

👉 See also: Am I Gay Buzzfeed Quizzes and the Quest for Identity Online

- Russia wanted a warm-water port.

- Austria-Hungary wanted to expand its influence.

- Britain just wanted to keep Russia from getting too powerful.

This created a shifting nightmare of borders. One year, Bulgaria is huge; the next, it’s tiny. Serbia gains a bit of land here, Montenegro gains a mountain there. When you look at a map of Europe in the 19th century near the year 1878 (the Treaty of Berlin), you see the seeds of World War I being planted. The borders were drawn by bureaucrats who didn't understand the ethnic realities on the ground. They were essentially drawing lines through people's living rooms.

Why 19th Century Maps Look "Off" to Modern Eyes

There are a few things that trip people up when they study these old documents. First, the colors. There was no "standard" color for countries, though Britain was usually pink or red (especially on global maps). Second, the "Austrian Empire" eventually became the "Austro-Hungarian Empire" in 1867. It’s the same landmass, but it’s a Dual Monarchy.

And then there’s Poland.

Poland basically didn't exist as a sovereign state for the entire 19th century. It was swallowed by Russia, Prussia, and Austria. If you see "Poland" on a map from 1840, it's usually labeled as "Congress Poland," which was basically a Russian province with a fancy name. It’s a ghost on the map.

The sheer number of micro-states is also wild. Even after German unification, there were still tiny principalities that kept their own postage stamps and local laws for a while. The map was "lumpy." It wasn't the smooth, bureaucratic surface we have now. Everything was personal. Borders were defined by which royal family married which other royal family, at least until the cannons started firing.

How to Read a 19th Century Map Like a Pro

If you're looking at a historical map and trying to figure out what year it is, look for these "tell" signs:

✨ Don't miss: Easy recipes dinner for two: Why you are probably overcomplicating date night

- Look at Belgium. If it's part of the Netherlands, you're before 1830.

- Check Germany. If it's a bunch of small states with a big Prussia, you're pre-1871. If it's one big block, you're post-1871.

- Find the Papal States. If the Pope still owns a giant strip of central Italy, it's before 1870.

- Look at the Balkans. If the Ottoman Empire goes all the way up to the Danube, you’re in the early 1800s.

The map of Europe in the 19th century is basically a visual record of the death of the old world and the birth of the modern one. It’s messy because the transition was messy. It was the century of the steam engine and the telegraph, but also the century of bayonets and cavalry charges.

Actionable Insights for Map Enthusiasts

If you want to actually understand this period without getting a headache, don't just stare at a static image. Use an interactive atlas like the Euratlas Georeferenced Historical Vector Data. It lets you toggle through years so you can actually see the borders "crawl" across the screen.

Another great resource is the David Rumsey Map Collection. They have high-res scans of actual 19th-century maps. You can zoom in and see the handwritten notes of cartographers. It makes you realize that these weren't just "facts"—they were claims. A map was a political statement. If a French cartographer drew the border one way and a Prussian drew it another, they were both lying a little bit.

To get a true handle on this:

- Trace one specific border (like the Rhine) from 1800 to 1900.

- Cross-reference maps with the "Year of Revolutions" (1848) to see where the fighting actually happened versus where the borders stayed the same.

- Ignore the colors and look at the city names. Sometimes cities change names when the border moves over them (like Pressburg becoming Pozsony and eventually Bratislava).

Understanding these shifts helps you see why European politics today is still so obsessed with history. The lines on the map of Europe in the 19th century may have been redrawn, but the scars they left are still there. You just have to know where to look.